Seighford Hall, a Grade II-listed building near Stafford, is a treasure trove of history. Its story spans more than 450 years, encompassing Tudor craftsmanship, ghostly encounters, industrial magnates, and even a stint as a nightclub. Today, the hall lies abandoned, but its legacy endures through its remarkable past.

Click here to watch my full video on Seighford Hall on YouTube

Listen to this article as a Podcast here

The Early Years: Richard Elde and the Construction of Seighford Hall

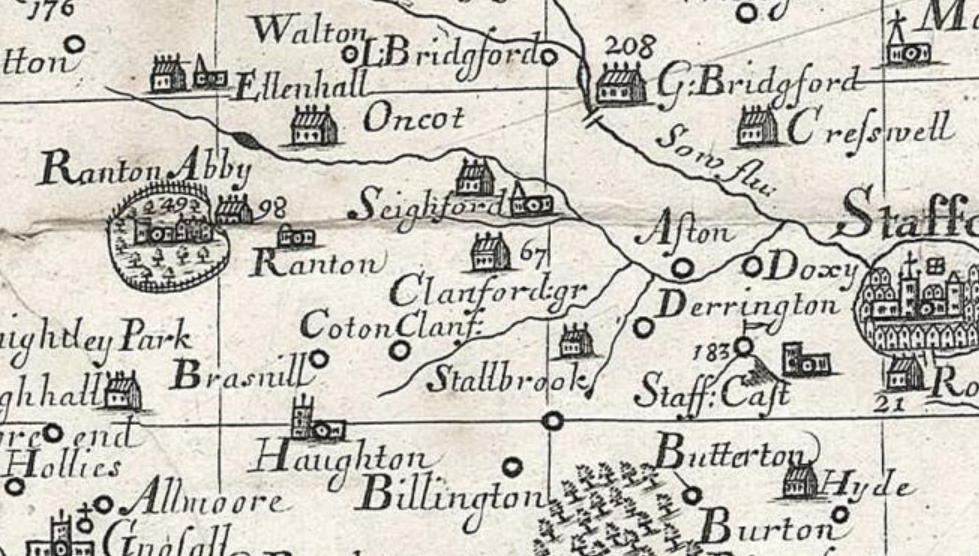

Seighford Hall was built in the late 16th century by Richard Elde (1546–1621), who acquired the land as part of his rise to prominence. Originally from Church Broughton in Derbyshire, Elde served as Treasurer and Steward to Walter Devereux, the 1st Earl of Essex (1541–1576), a significant figure in Elizabethan England. Devereux, 11th Baron Ferrers of Chartley and Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire, likely facilitated Elde’s acquisition of the Seighford estate, positioning him within the Staffordshire gentry.

In 1574, Elde was granted a coat of arms and crest by the Ulster King of Arms, solidifying his status among England’s rising gentry. This heraldic recognition reflected Elde’s growing influence and wealth, derived from his trusted administrative roles under the Earl of Essex. Elde’s work as a paymaster during Essex’s military campaigns in Ireland further underscored his responsibilities, as he managed funds and logistics for the Earl’s operations.

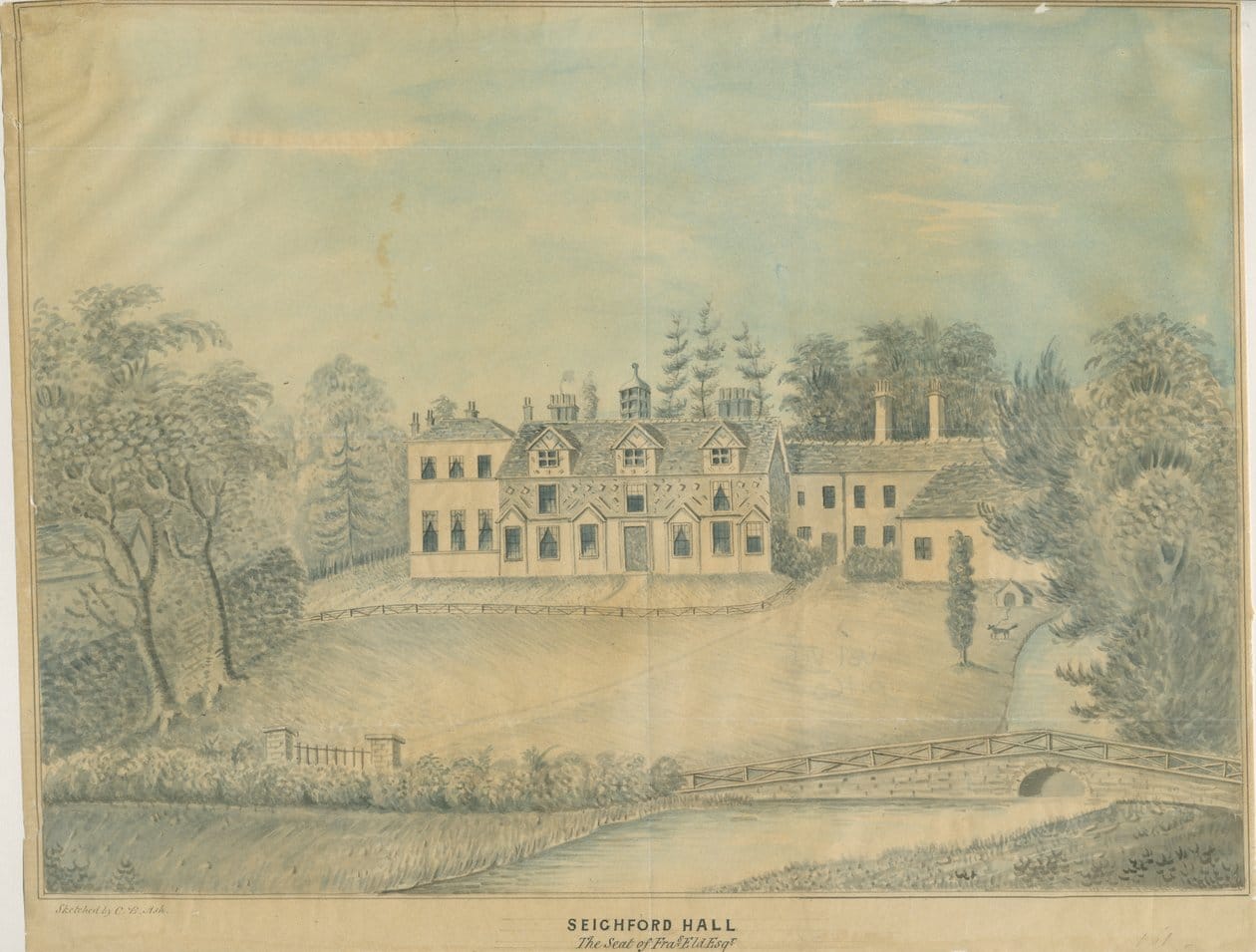

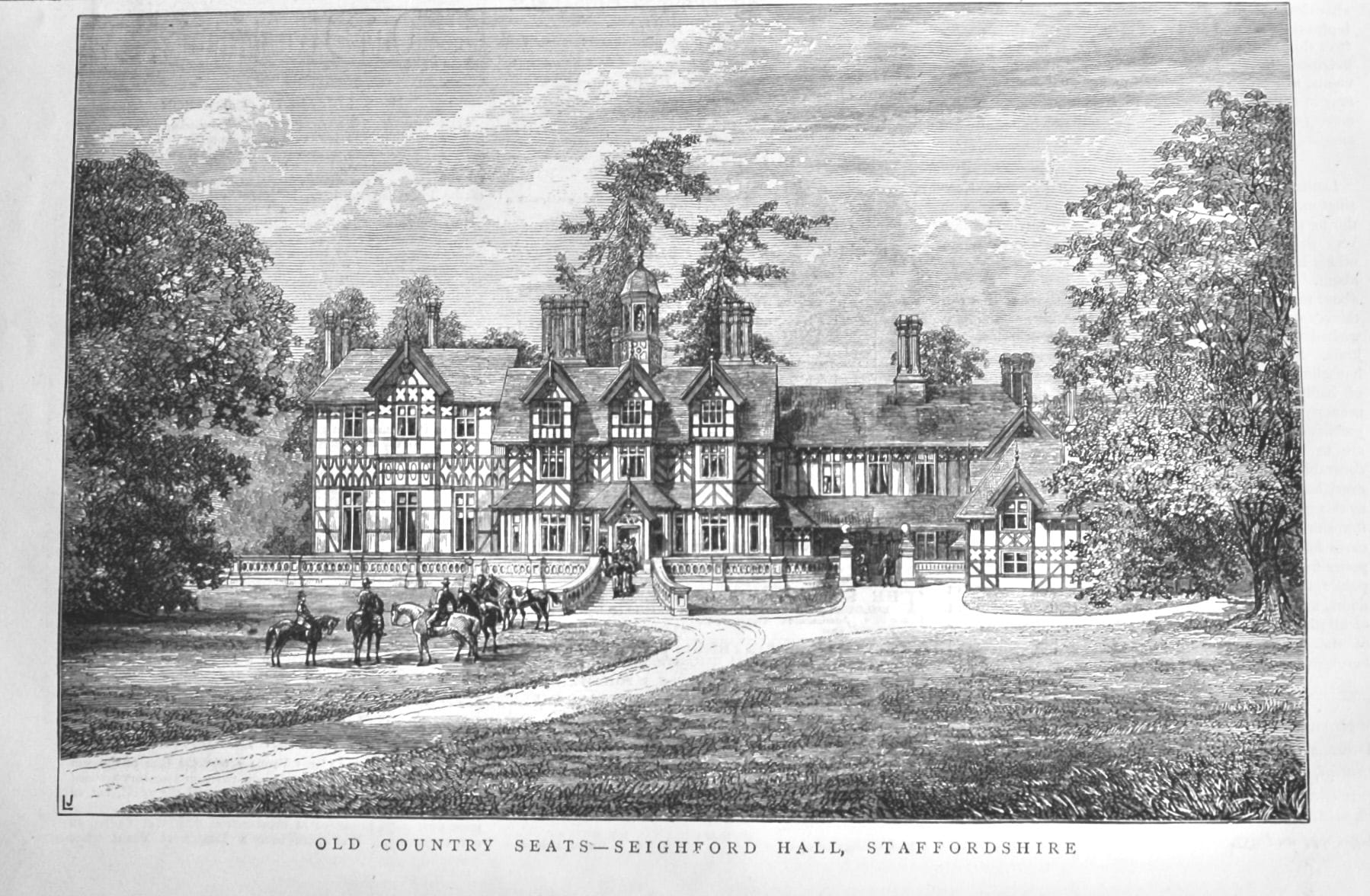

Seighford Hall was constructed on a greenfield site, indicating a deliberate effort to establish a new family seat. The hall was designed in the Tudor architectural style, featuring timber-framed construction, small panel framing, and decorative bracing. These elements, common to late Tudor domestic architecture, combined aesthetic appeal with structural durability. The hall’s double-pile layout, a hallmark of higher-status homes of the period, further emphasised its importance.

The Staffordshire Hearth Tax of 1666 records that Francis Elde, Richard Elde’s descendant, was assessed for six hearths, placing Seighford Hall among the larger homes in the area. While smaller than Sir Thomas Whitgreave’s nearby estate, which had eight hearths, the hall’s size and design marked it as a significant residence. Its timber-framed structure, though modest compared to the grand estates of the aristocracy, reflected the wealth and aspirations of its owners.

Richard Elde’s connection to Walter Devereux not only influenced his acquisition of the estate but also tied Seighford Hall to broader historical events. Devereux’s campaigns in Ireland, known for their severity, were supported by Elde in his role as Treasurer. This involvement placed Elde in a position of considerable responsibility and trust, reinforcing his ability to secure resources for the construction of the hall.

The Eld Family Legacy

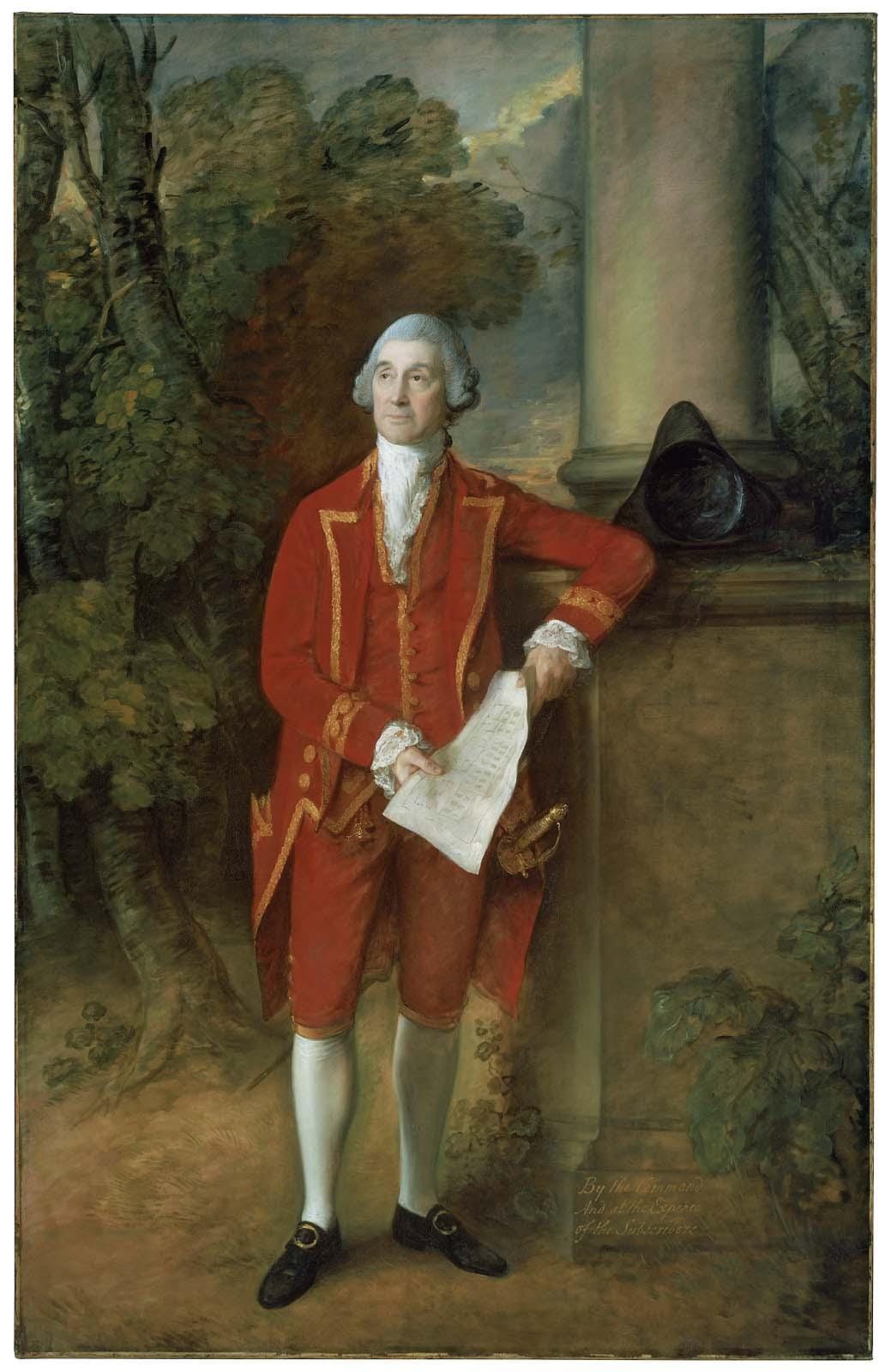

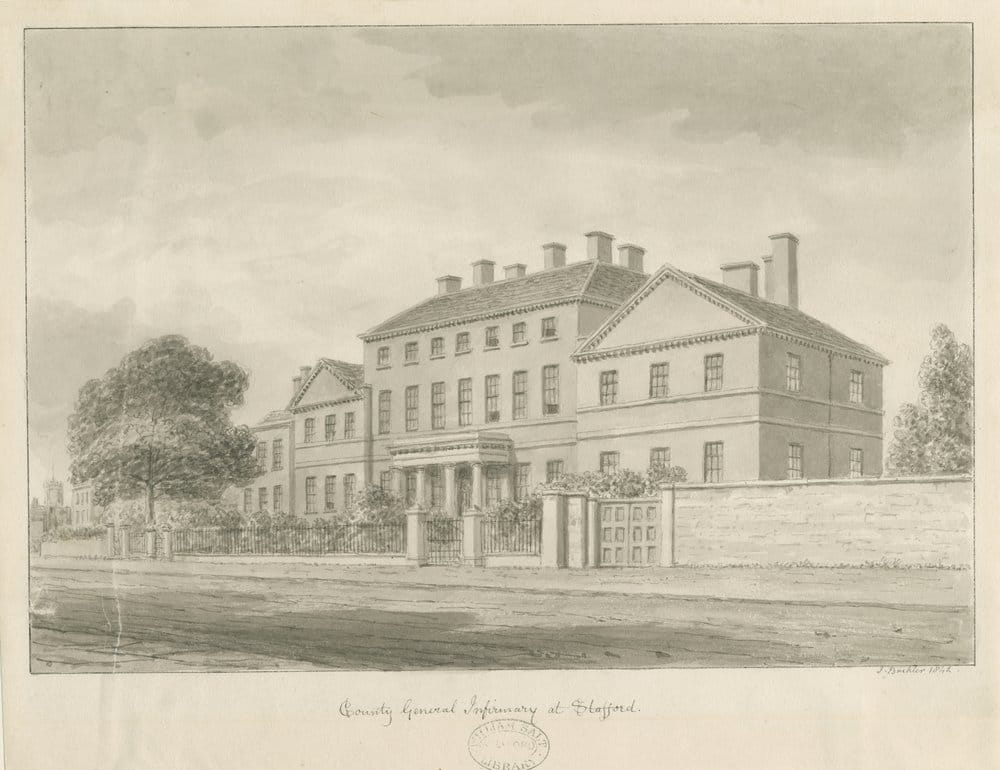

The Elde family retained ownership of Seighford Hall for centuries, shaping its history and leaving a lasting impact on Staffordshire. After the death of Francis Elde in 1760 without issue, the estate passed to his half-brother, John Elde of Dorking, Surrey. John, a prominent figure of his time, played a significant role in the development of public infrastructure in the county. Notably, he was a key benefactor of the Stafford General Infirmary, a critical healthcare institution constructed between 1769 and 1772. His contributions to the infirmary were commemorated in a full-length portrait by the renowned artist Thomas Gainsborough, which depicts John holding the plans for the building.

John Elde lived to the remarkable age of 92, passing away in 1796. The estate was then inherited by his son, Francis Eld, who continued the family’s legacy and stewardship of Seighford Hall. Born in the mid-18th century, Francis undertook significant renovations to the hall, reflecting the architectural tastes of the Georgian period. These included the addition of brick wings to either side of the original timber-framed structure. This marked a departure from the hall’s Tudor origins, introducing a more modern and symmetrical aesthetic that was popular among the gentry of the time.

The Georgian modifications not only updated the hall’s appearance but also expanded its functionality, ensuring it remained a desirable residence for the family. A watercolour painting by Thomas Peploe Wood in 1838 captures the hall’s transformed appearance, showcasing the Georgian brick additions alongside remnants of its original Tudor framework.

These renovations represented a period of prosperity for the Eld family, who maintained their presence as prominent landowners in Staffordshire. Their stewardship of Seighford Hall not only preserved the estate but also adapted it to the changing tastes and needs of successive generations, embodying the family’s enduring influence.

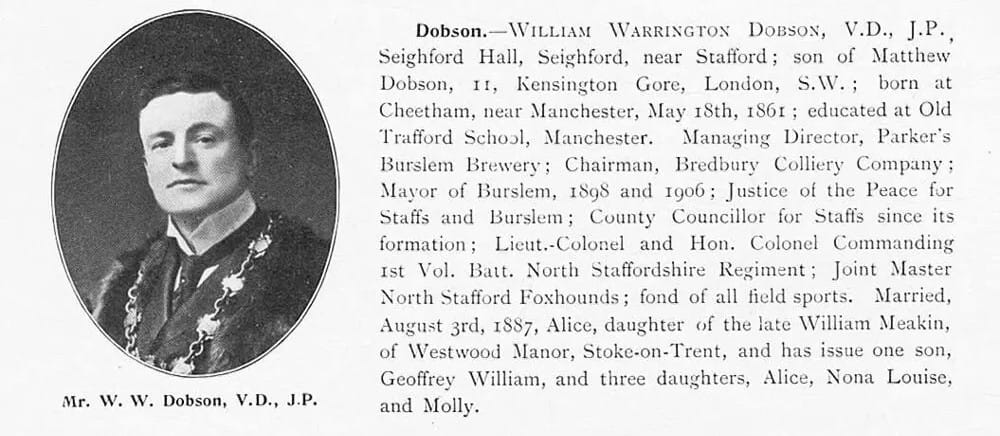

Colonel William Dobson: A Modern Pillar of Staffordshire

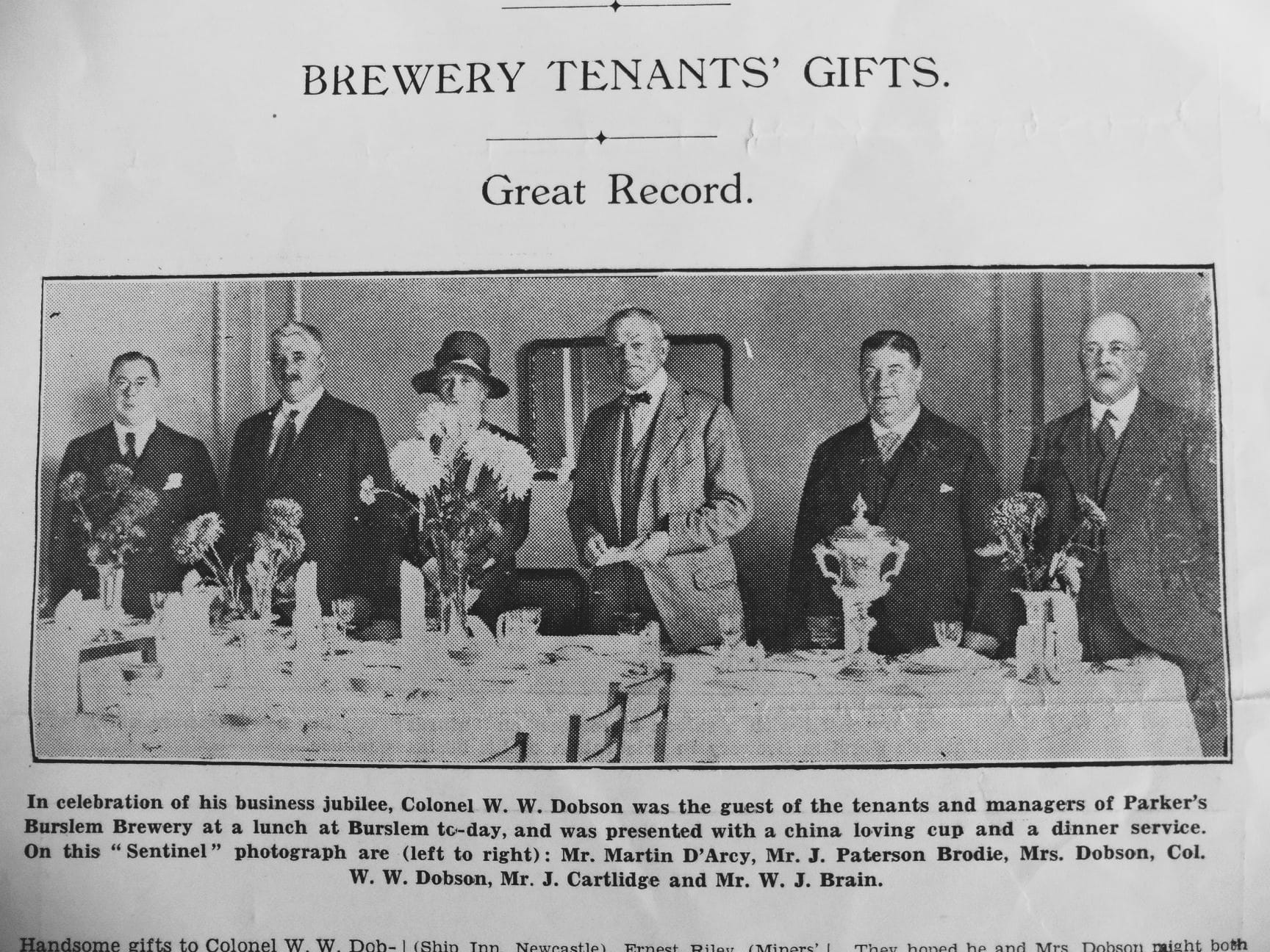

In the early 20th century, Seighford Hall became the residence of Colonel William Warrington Dobson (d. 1941), a prominent figure in Staffordshire’s industrial, social, and civic life. Dobson’s influence was deeply rooted in the town of Burslem, where he chaired Parker’s Brewery, a cornerstone of the local economy. Under his leadership, the brewery employed many in the Potteries, fostering economic stability and community spirit during a time of significant industrial and social change.

Dobson’s contributions extended beyond business. Appointed High Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1915, he embodied civic responsibility and leadership. His military service was equally distinguished, as he played a key role in organizing the Staffordshire Territorial Association, which supported the county’s wartime efforts. He served as Honorary Colonel of the 41st Searchlight Regiment, a position he held until his death, reflecting his commitment to national defence and local military readiness.

Dobson’s philanthropy was an integral part of his legacy. He was especially devoted to improving the lives of children in Burslem, ensuring that Christmas was a time of joy for the less fortunate. In his will, he left £1,000 to fund annual Christmas treats for poor children, which included tea parties and concerts. During World War II, Parker’s Brewery subsidized these events to maintain the tradition despite wartime hardships. In 1933, the towns of Burslem and Stoke honoured him with a magnificent presentation casket made by Doulton. The ceramic casket, adorned with his family crests, the town crests of Burslem and Stoke, and intricate gilded designs, was a tribute to his enduring contributions to the local community.

During Dobson’s tenure at Seighford Hall, the estate became a hub of social and cultural activity. The North Staffordshire Hunt regularly met on the grounds, reflecting its importance within the county’s social calendar. The hall’s extensive grounds and historical charm made it a fitting venue for these gatherings, which drew participants from across the region.

North Staffordshire Hunt meet, Seighford HallHuntsmen, hounds and followers at a North Staffordshire Hunt meet at Seighford Hall.Seighford Hall is an Elizabethan timber-framed house with Victorian additions and was the home of Colonel Sir William ...View Full Resource on Staffordshire Past Track

Dobson’s death in 1941 marked a turning point for Seighford Hall. With no immediate heirs to take over the estate, the hall was left empty, beginning a period of decline. During World War II, the hall took on a new role, serving as a post for the Home Guard. Its saddle room was converted into an armoury, storing grenades, rifles, and other weaponry to support the nearby RAF Seighford airstrip. At the same time, Seighford Hall became a YWCA hostel for off-duty members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAFs), offering them a place to relax and socialize. Male visitors were allowed during designated hours but were strictly prohibited from staying overnight, adhering to wartime regulations.

Despite these adaptations, the absence of Dobson’s stewardship left a void. His dedication to preserving the estate and his contributions to Staffordshire society had given Seighford Hall a vibrancy that could not be easily replaced. His death not only signalled the end of an era for the hall but also underscored the challenges of maintaining such historic estates without dedicated leadership.

Architectural Evolution

Seighford Hall’s architecture reflects the changing tastes and needs of its owners over the centuries, evolving from its late 16th-century Tudor origins into a property that blended multiple styles and influences. Initially constructed as a timber-framed house with small panel framing and decorative bracing, the hall’s Tudor character formed the foundation of its identity. However, successive generations of owners adapted and expanded the estate, leaving a layered architectural legacy.

Significant modernisation occurred during the Georgian period in the late 18th century when brick wings were added to the original structure. These wings, symmetrical in design, introduced the balanced proportions and large sash windows typical of Georgian architecture. This transformation marked a shift away from the Tudor aesthetic, embracing the restrained elegance that defined the era. These changes were likely implemented during the tenure of Francis Eld, who inherited the estate in 1796 and oversaw substantial improvements to the hall.

Further alterations in the 19th century reflected the Victorian fascination with revivalist styles. The hall was remodelled to include a mock Tudor façade, obscuring much of the original timber framing. This decorative treatment, popular in the Victorian era, sought to evoke the romance of medieval and Tudor architecture while incorporating modern materials and techniques. Internally, the hall was updated in a mid-Victorian baroque style, introducing ornate detailing that contrasted with the simplicity of its earlier construction.

Pevsner’s architectural survey of Staffordshire notes additional features contributing to the hall’s character, including a coach house, a gamekeeper’s cottage, and a distinctive brick tower designed to resemble a church spire. These elements reflect the estate’s functional and aesthetic development over time, serving both practical and decorative purposes.

The hall’s grounds, though smaller than in its original form, also bear the marks of its evolution. Ornamental ponds on the property are believed to have been former fish stews, a practical feature common to estates of its age. A centrally placed walled kitchen garden provided produce for the household, while formal walks and pathways, now overgrown, hint at the estate’s past grandeur.

The Haunting of 1785

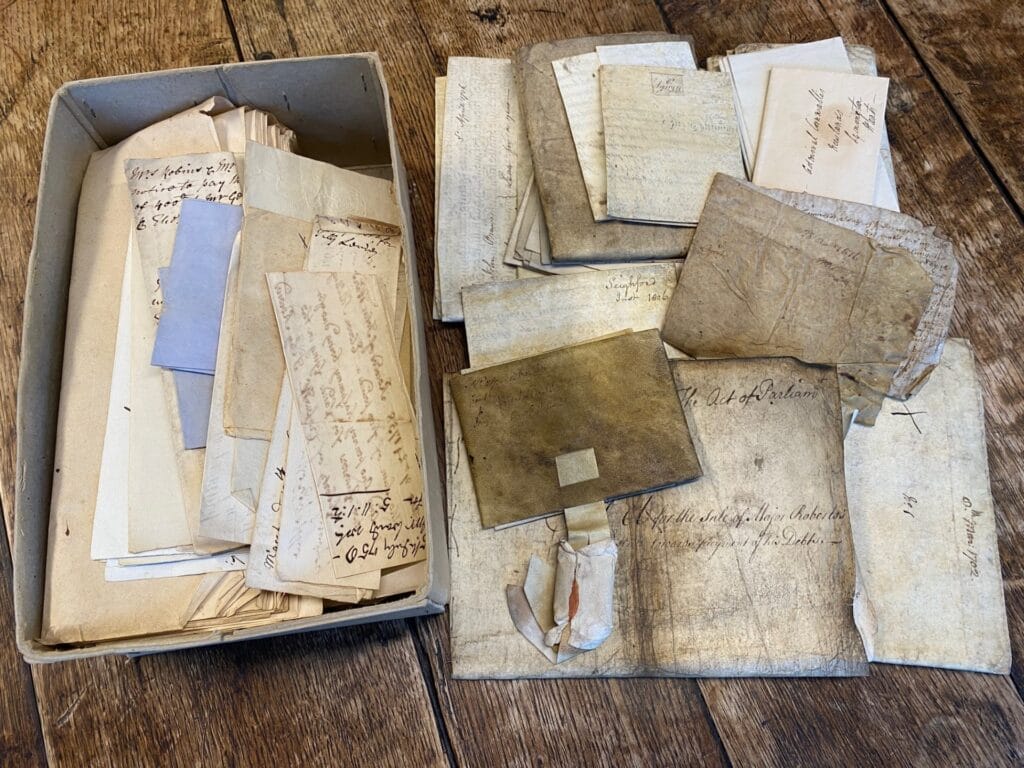

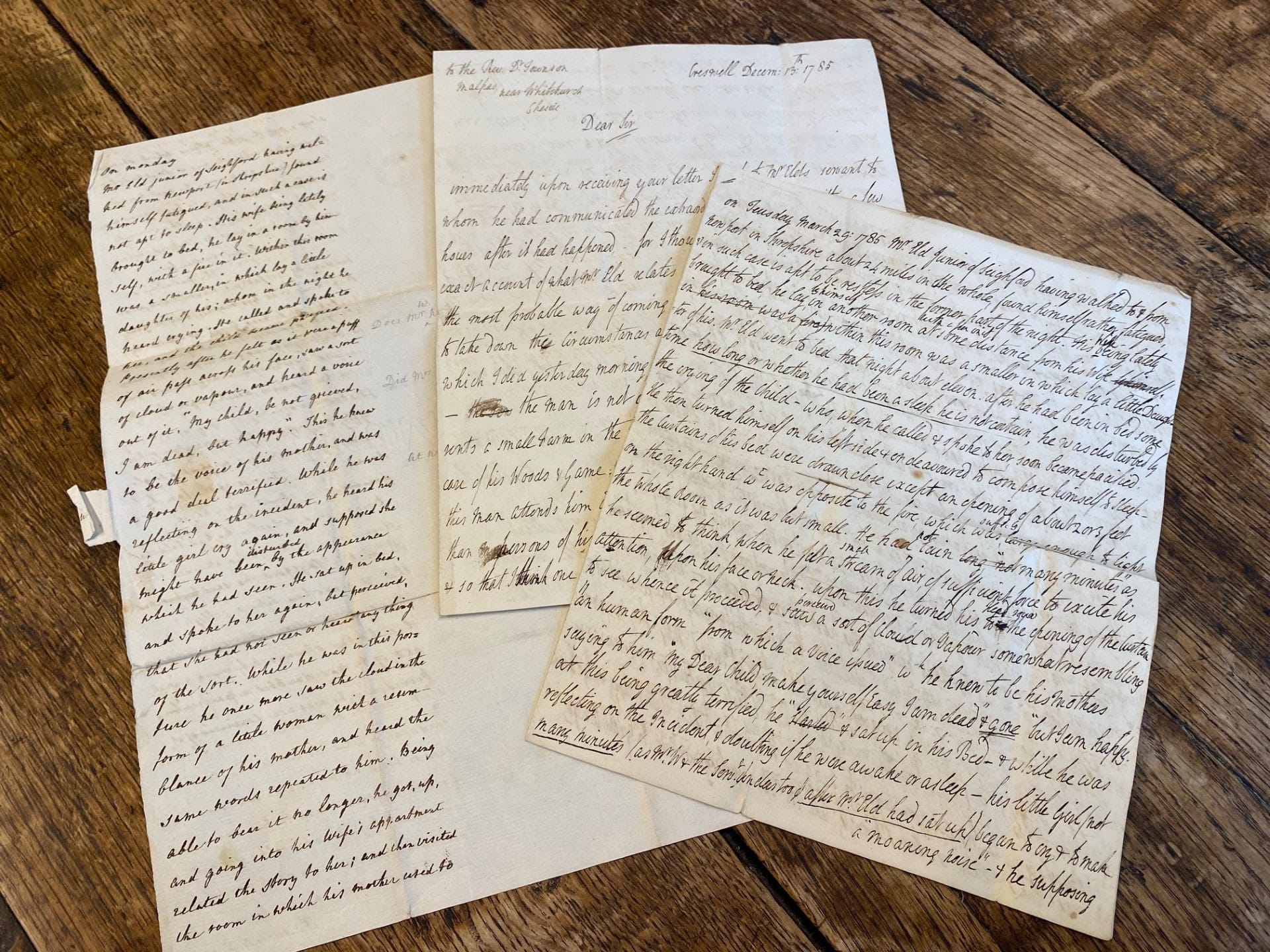

One of the most enduring and enigmatic stories tied to Seighford Hall is the haunting of Francis Eld, an event documented on the night of March 29, 1785. Manuscripts discovered among old deeds by Jim Spencer, Director at Rare Book Auctions, Lichfield. They recount how Eld, then residing at Seighford Hall, was visited in the early hours by an apparition of his mother. As the story goes, Eld felt a sudden "puff of air" across his face before witnessing a cloud of vapour that took on his mother’s form. The apparition spoke to him, saying, “My child, be not grieved. I am dead but happy.”

At the time of the visitation, Eld was unaware of any misfortune regarding his mother, who was living at Pit Place in Surrey. However, deeply unsettled, he resolved to confirm her wellbeing. The following day, he sent a servant to Stafford Post Office, where a letter awaited him. The letter, dated two days earlier, described his mother as “tolerably well” and noted that she had recently enjoyed a hearty meal of hare sent to her by Eld himself. This reassured him temporarily, but doubts persisted.

Just days later, on April 1, Eld received another letter, this one confirming his worst fears. His mother had passed away on the night of March 28–29, precisely at the time of the visitation. The shock of realizing this uncanny coincidence reportedly caused Eld to faint. His account of the event later shared with his father during the funeral, left his father equally shaken.

The haunting was documented in detail by Reverend Thomas Whitby of Creswell and Reverend Townson of Malpas, Cheshire, who discussed the “very uncommon event” in correspondence. The testimony of Eld’s servant, also recorded by Whitby, lent further credibility to the story. Whitby described the servant as a man of integrity and intelligence, stating, “The man is not a common menial servant but one who rents a small farm in the neighbourhood... He is more sensible and intelligent than persons of his situation usually are, bold and resolute so that I think one may venture to depend upon the accuracy of his relation.”

The tale captivated contemporaries, its eerie details and timing reinforcing its impact. Unlike many ghost stories of the period, this account was treated with serious attention, partly because of its documentation by clergymen and the personal testimony of those involved. The story remains one of the defining chapters in Seighford Hall’s history, adding a layer of mystery to the estate’s already storied past.

From Nightclub to Nursing Home

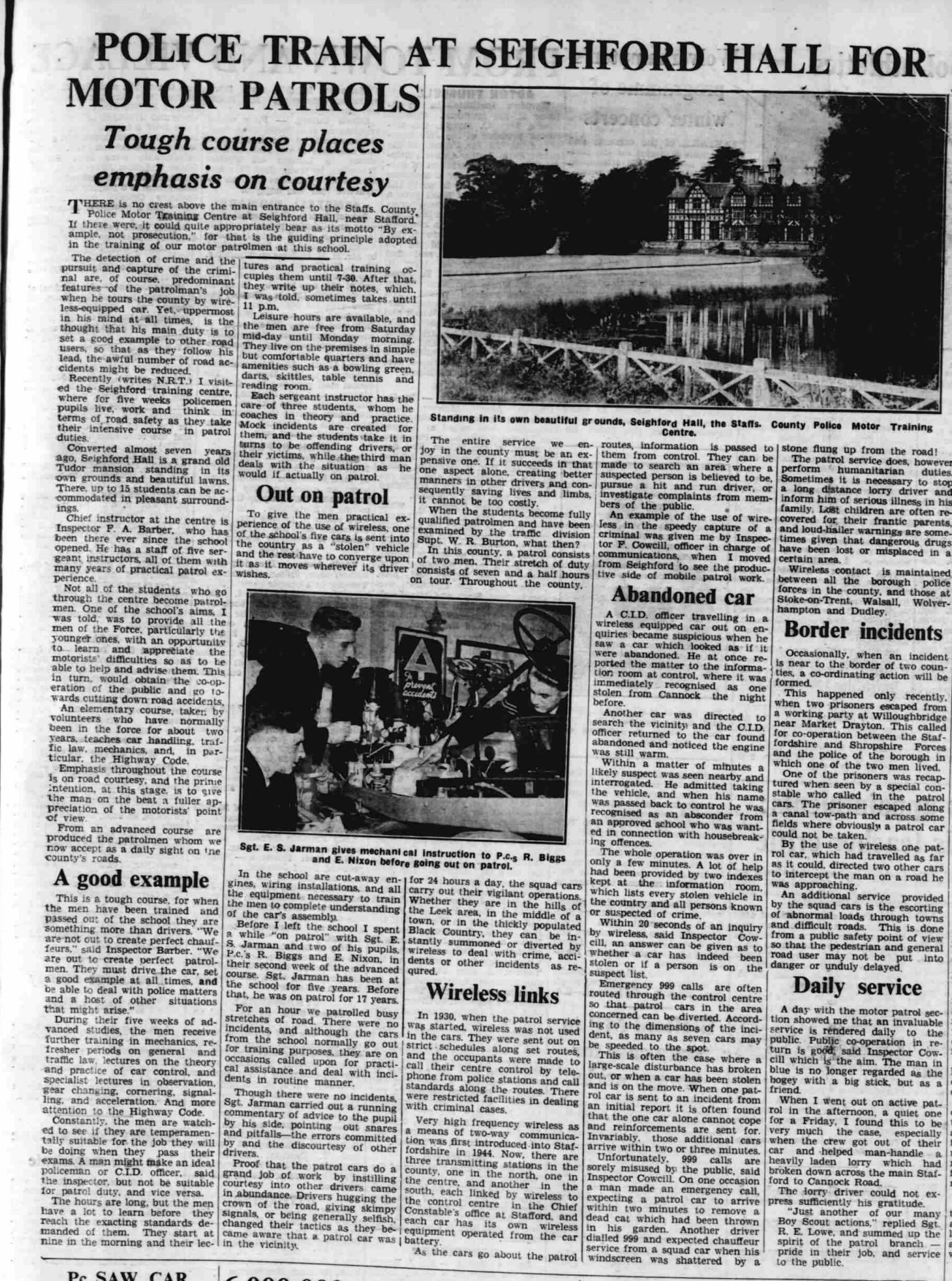

By the mid-20th century, Seighford Hall had begun a series of transformations that reflected its shifting fortunes and changing utility. From 1947 to the 1950s, the hall served as Staffordshire Police’s driving school. The estate’s spacious grounds and rural location made it an ideal site for training, offering a secluded environment for honing driving skills. This practical use marked a departure from its historical role as a family residence but underscored its adaptability.

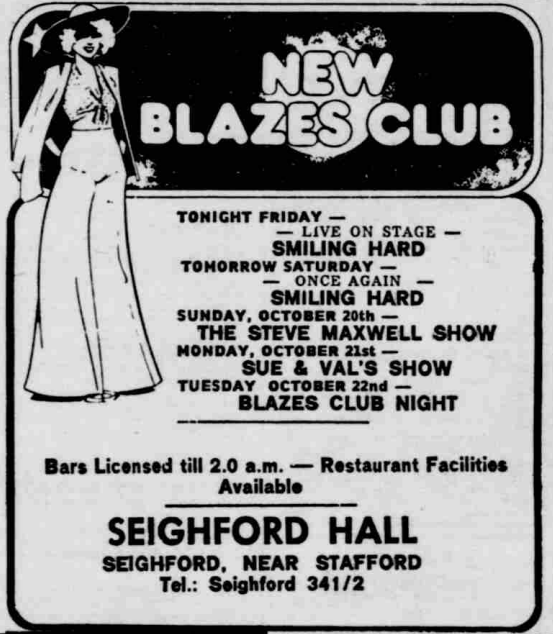

In the 1970s, Seighford Hall took on a dramatically different identity as "Blazes Nightclub." During this period, the hall became a hub for social gatherings, drawing crowds from across Staffordshire and beyond. Its picturesque setting and unique historical atmosphere added a sense of grandeur to the nightclub experience, making it a popular venue. This era also brought an air of levity to the hall’s history, as it became known for lively events and entertainment.

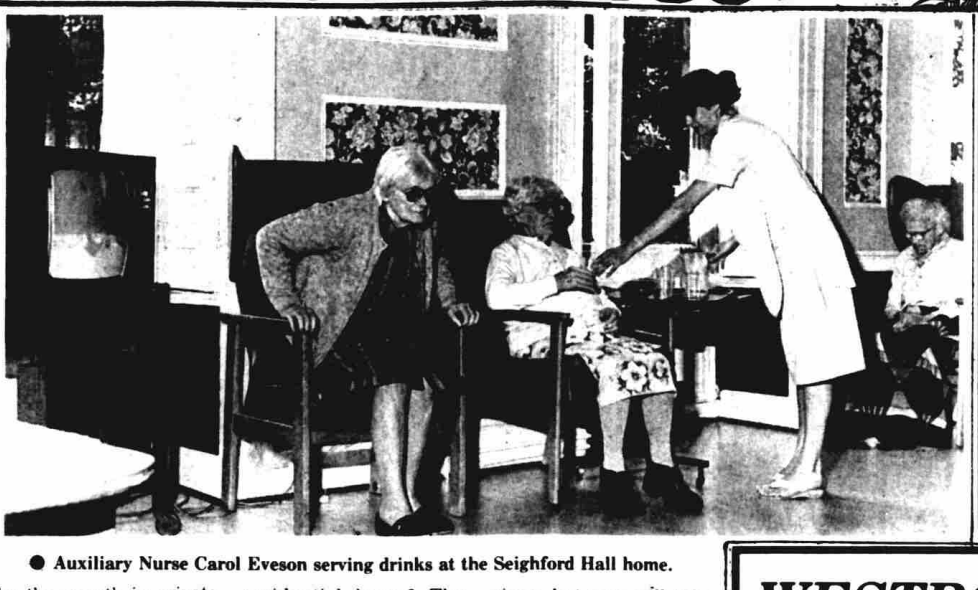

By the 1990s, Seighford Hall’s role had shifted once more, this time as a nursing home. This phase of its history was brief but significant, reflecting the growing need for elder care facilities during this period. The hall’s large rooms and expansive grounds made it a practical choice for such a purpose, even as the cost of maintaining a historic building presented challenges. Despite its potential, this chapter in the hall’s history was short-lived, and the nursing home ultimately closed.

By the early 2000s, Seighford Hall had fallen into disuse once again. Its abandonment marked the beginning of a long period of neglect, during which the hall’s condition deteriorated significantly.

The £5 Million Tudor Artefact Scandal

One of the most bizarre and costly episodes in Seighford Hall’s history unfolded in the 21st century, centring on the removal of a rare 16th-century oak overmantel valued at up to £5 million. This intricately carved Tudor artefact, believed to be between 417 and 462 years old, bore Queen Elizabeth I’s coat of arms alongside detailed depictions of a lion and dragon, lyres, hanging fruit, and figures influenced by French and Italian design. The overmantel was an integral part of the Grade II-listed hall’s historical fabric, having hung above one of its fireplaces for centuries.

The controversy began when Brian Wilson, a long-time caretaker of the hall, removed the overmantel, claiming it was “riddled with woodworm and dry rot.” Living in a caravan on the derelict estate, Wilson had been employed to oversee maintenance and security after the building ceased operating as a nursing home in 1998. Without seeking permission, he placed the overmantel on a fire pile and subsequently allowed Andrew Potter, a local businessman and antiques dealer, to take it away. Wilson later explained, “I let him have it. As far as I was concerned it was less rubbish for me to get rid of.”

Unaware of the artefact’s immense value, Potter initially planned to repurpose the nearly 9-foot-wide overmantel as a headboard. However, after recognizing its significance, he consigned it for auction. The overmantel, described by auctioneers as a rare and culturally significant object, was expected to fetch between £1.9 million and £5 million. This prompted Stafford Borough Council to intervene, applying for an injunction to prevent its sale, citing the lack of listed building consent for its removal.

The council argued that the overmantel, as an original fixture of Seighford Hall, was protected under heritage law. A temporary injunction was granted, halting the sale and requiring Potter to disclose the artefact’s location, which was eventually revealed to be a self-storage unit in Telford. Although the case was ultimately dropped in 2021, the council made it clear that selling the overmantel without proper permissions would constitute a criminal offence under the Dealing in Cultural Objects (Offences) Act.

The scandal deepened when it emerged that Wilson had previously sold other items from the hall, including fireplaces and a tractor, without authorization. Wilson was dismissed in 2020 for gross misconduct following these revelations, though he contested his dismissal at an employment tribunal. The tribunal ruled that while the sacking had been “procedurally unfair,” Wilson’s actions were blameworthy, and he was awarded only a small sum for unpaid wages and holiday pay.

Today, the overmantel remains unsold, its fate uncertain. This episode highlights the vulnerabilities of heritage properties, particularly those left derelict and poorly managed. What began as a caretaker’s misguided attempt to clear perceived rubbish has become a cautionary tale of how neglect and mismanagement can jeopardize priceless historical treasures. For Seighford Hall, the loss of such a significant piece of its history remains a stark reminder of the challenges of preserving cultural heritage.

Modern Decline and Abandonment

In 2020, Seighford Hall was purchased by First Blue Group for £275,000, following nearly two decades of abandonment. The Grade II-listed building, with its rich history dating back to the 16th century, was intended to be transformed into a luxury hotel and spa. First Blue Group announced ambitious plans to invest £15 million into the project, envisioning a 64-bedroom hotel with log cabins, a walled garden, and a restaurant showcasing local and homegrown produce. The development also promised to preserve the hall’s historical character while introducing modern amenities, offering an idyllic retreat in the Staffordshire countryside.

Despite these grand intentions, progress on the redevelopment soon stalled. Although repair work began, including initial stabilisation efforts, the project appears to have come to a halt. As of late 2024, Seighford Hall remains derelict, its grounds overgrown and its interiors in a state of significant decay. The hall’s current condition has become a point of local curiosity, with reports of peculiar finds such as a floor covered in snail shells, adding an eerie quality to its decline.

The hall’s abandonment has compounded the challenges of preserving its historical fabric. Years of neglect have left the building vulnerable to weather damage and vandalism, and no updates on the project’s future have been forthcoming from First Blue Group. The hall’s inclusion in SAVE Britain's Heritage's Buildings at Risk Register in 2020 underscores the urgency of its plight.

Seighford Hall’s modern decline is a stark contrast to its former grandeur, reflecting the difficulties of balancing commercial ambitions with the practicalities of restoring a historic estate. While the property’s potential as a luxury destination remains undeniable, its current derelict state is a sobering reminder of how easily heritage can slip into decay when restoration efforts falter. For now, the hall stands as both a symbol of lost opportunity and a challenge for those who wish to see its story continue.

Seighford Hall’s journey through history is one of grandeur and neglect, triumph and tragedy. From its Tudor beginnings under Richard Eld to its modern state of dereliction, the hall has been a witness to centuries of change. Each chapter of Seighford Hall’s history, from its role as a family estate to its transformation into a police training school, nightclub, and nursing home, reflects the changing face of England itself.

Now, as this once-proud estate faces an uncertain future, Seighford Hall serves as a poignant reminder of both the fragility and the enduring allure of England’s heritage. Its story calls for greater appreciation and care for historic properties, lest they slip into obscurity. Seighford Hall, with all its beauty and complexity, remains a symbol of the challenges and possibilities of preserving the past while looking to the future.

Love local history? Support my work and uncover Stoke-on-Trent's stories here;

Thank you.