The Fauld Explosion

At 11:11 am on the 27th of November 1944, an explosion occurred that would forever change the face of the Staffordshire countryside.

Near the small, rural village of Hanbury, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had chosen a gypsum mine as their underground ammunition store during WW2. Becoming larger and larger as the war went on, eventually, over 40,000 tonnes of ammunition were stored in the mines.

That is, until the fateful day in 1944 when around 4,000 tonnes of ammunition, including 500 million rounds of rifle ammo, exploded, causing catastrophic damage and a 12-acre crater that still remains today.

RAF Fauld: Storing Ammunition for WW2

For hundreds of years, gypsum has been mined in South Staffordshire. This stone has been mined for the creation of alabaster gypsum plaster to be used in construction. In the 19th century, gypsum mining became a commercial venture at Fauld and a large gypsum mine grew on the site.

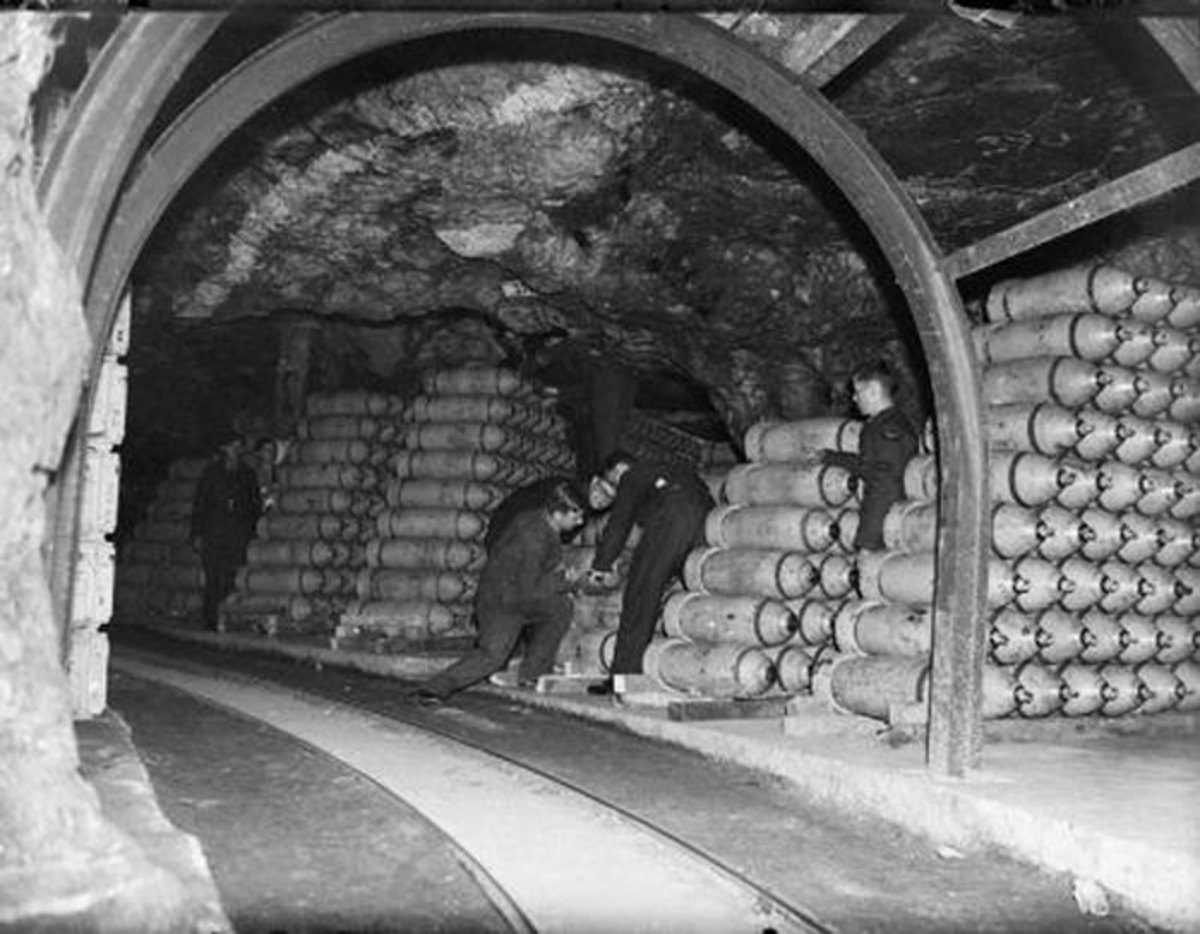

In 1937, the RAF requisitioned an unused gypsum mine next to Peter Ford's plaster works in Fauld to store ammunition underground, 90 feet below Stonepit Hills. This underground area was chosen because of its rural location and its size, which was enough at that time to store 10,000 tonnes of bombs and ammunition, which would eventually be expanded up to 40,000 tonnes.

The mine proved a good place to store the munitions, as the mining had left natural rock pillars to support the roof every 20 feet. The RAF added a concrete roof and two walls, one 10-foot and one 50-foot thick, to separate the explosives from the incendiaries.

To transport the munitions, a light railway was built to transport from the inside of the mine to the main railway line at Scropton.

Near to the store was a live gypsum mine owned by Peter Ford Ltd. It was decided by experts that there was no risk to this live mine as there were natural walls of rock up to 50 feet thick between them that would act as a good enough blast barrier.

This store was run and maintained by RAF Maintenance Unit 21, better known as 21 MU. The records of who was working there at the time were not very well kept, but it seems that there were around 18 officers, 475 servicemen and 445 civilians, and in 1944, 195 Italian prisoners of war were bought in from a POW camp at Hilton.

The Explosion

On the morning of the 27th of November 1944, an armourer working in the store found a damaged exploder on a 450kg bomb that was in a pile of similar bombs. He tried to remove the exploder, but he, unfortunately, used a brass chisel, which was strictly against regulations as it caused sparks.

This spark set off the bomb, which in turn set off nearly 4000 tonnes of the explosives stored in the mine. This included 1,500 two-tonne 'Blockbusters,' The RAF's town-destroying, highly explosive bombs.

The actual explosion was at 11:11 am, and reports say that there were two. The first was a loud, sharp crack which was quickly followed by an incredible blast.

The explosion under the ground created a huge mushroom cloud and caused a million tonnes of earth and rock, including the roof of the mine and the 90 feet of rock and earth above it, into the air. The dust rose an estimated 11 miles into the sky.

Huge pieces of gypsum, some weighing over 20 tonnes landed in the surrounding areas.

The dust fell for over three hours, covering everything for miles around in a thick layer and making it eerily quiet.

The Extent of the Damage

The size of the explosion is unimaginable. The explosion was heard as far as London. A plane saw the flash from over 100 miles away. The blast even registered on a seismograph in Switzerland. Children at a local school were made to hide under their desks.

The local pub, The Cock Inn, nearly a mile away, was severely damaged and had to be rebuilt, as did the village hall. Five miles away in Burton-upon-Trent, 150 houses were damaged, and two church spires cracked; one had to be dismantled. In Tutbury, chimney pots and roofs were broken.

Upper Castle Hayes Farm was above the site of the explosion and disappeared completely. Hanbury Fields Farm was a quarter of a mile away and was completely buried in falling earth and rock.

The whole area was strewn with the dead bodies of cattle, sheep and fish.

The 30-foot dam of a nearby reservoir was also damaged, and this caused a wave over 15 feet high and full of earth, trees and rocks down onto Ford's plasterwork factory. This wave destroyed the buildings and buried the workers.

The Rescue Operation

Rescue teams came in from many miles around as news of the explosion spread. However, the rescue was very slow due to a lack of lamps and a large amount of carbon monoxide in the mine. They had to install fans to try to ventilate the mine before anyone else could go in and search.

There was also the fact that there were still thousands of tonnes of unexploded ordinance in the mine.

Americans from a service hospital at Sudbury rescued men from the nearby Peter Ford plasterworks. Prisoners from Sudbury Open Prison were used to clear the debris from the fields.

The progress was slow, and some bodies were found weeks later; some were never recovered, nor were many tonnes of ammunition, as it was just too dangerous to search deep within the mine.

Even two years after, one man hit something metal whilst farming, which turned out to be a tractor and the body of the operator who was driving it when the explosion occurred.

Some of the People Involved in the Explosion

Mary Cooper was looking after the elderly mother of a farmer when the blast occurred. She quickly pulled her under the table, and they both survived. The farmer and his wife survived because they were away at the market. Everyone else on the farm died.

Joseph Cooper, Mary's husband, died in the blast as he was driving a train in the mine at the time of the explosion. His wife Mary volunteered to lay the bodies out and he was among them.

John Auden, the coroner for East Staffordshire at the time, said:

"This woman, of her own free will, has cleaned and scrubbed a very gruesome temporary mortuary every day for 72 days. The work has been indescribable. She has helped with the undressing, and also with the washing of clothes removed from the victims. One of the first victims she had to deal with was her own husband. In most cases that would have been sufficient for a middle-aged woman to undertake without volunteering to continue the work with all the remainder. She survived the wrecking of a farm at which she was looking after an old lady, and it is probably due to her action that the old lady's life was saved."

RAF Corporal Lionel Poynton was caught in the blast and crawled for an hour in complete darkness, collecting survivors by feeling the rail tracks until they got to safety.

Arthur Harris worked at RAF Fauld. Before he died, his knowledge of the site allowed him to save many lives. He returned to the crater to continue rescuing when there was another explosion that killed him.

The Aftermath

The blast caused a crater that covers over 12 acres and is 120 feet deep. At the bottom of the crater are what is left of the support pillars from the mine. The story soon hit national headlines as one of the worst wartime disasters at home. The Daily Mail exaggerated as usual and said that over 200 people had died. The government criticised the newspaper, saying it was damaging public morale. (Nothing new there, then).

The official report stated that 90 were killed, missing or injured, including 26 in the mine, a mix of RAF personnel, civilian workers and Italian POWs. There were 37 killed or missing at Peter Ford & Sons gypsum mine and plaster mill and surrounding countryside, and 12 were also injured. Approximately seven farm workers were killed at Upper Castle Hayes Farm. One person was killed during the search and rescue.

Many animals were also killed.

The Germans claimed it was sabotage. Conspiracies went around that it was the IRA or the Italians, a bomb from an enemy plane, or even a new German V2 flying bomb.

The results of an inquiry were only made public 30 years later, in 1974, and declared that the explosion was an accident.

They managed to remove thousands of tonnes of unexploded bombs in the clean-up, but it is estimated that there are still over 3000 tonnes of unexploded ordinance in the collapsed mine that was unreachable. A freedom of information act request confirmed this information.

A relief fund was organised by the local people to pay the families of the victims and survivors until 1959.

There was a shallow instrument search between 1966 and 1969 and a visual search between 1974 and 1976, but the unexploded ordinance was stored deep in the mines that had collapsed, and it was too dangerous to try to recover them.

The site was still used to store munitions by the RAF until 1966 when No21 MU was disbanded. It was then used by the USA to store ammo previously stored in France.

The Site Today

Today the crater is still there and visible, and you can visit the site, although the crater itself was fenced off in 1979. There are walks and public footpaths around it, though, and the area is a haven for wildlife, with over 150 species of trees. Along the path and in the nearby fields, you will see large pieces of gypsum, which are still in the places where they fell from the explosion.

The area is not safe due to the unexploded ordnance. As the bombs deteriorate with age, the risk that they pose rises. Fauld is one of a few sites in the UK where unexploded ordnance from WW2 still poses an ongoing threat.

The MOD said that the edge of the crater and the fence are inspected annually by 5131 Squadron (Bomb Disposal). The results of that report are sent to the Explosives Safety Representative and Health and Safety Representative at RAF Cosford.

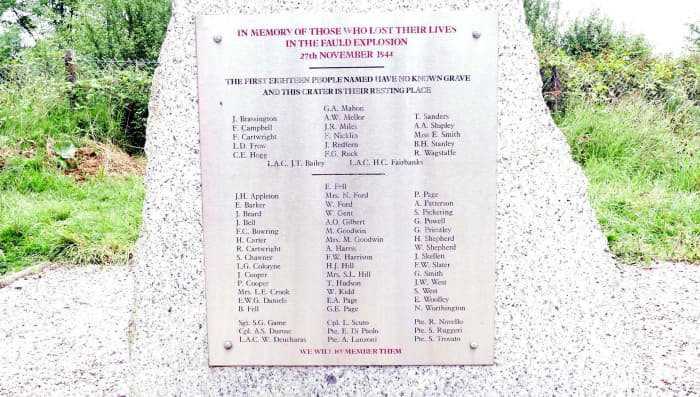

A memorial stone was created using a stone donated by the Italian government, which was flown to the UK on an RAF plane and unveiled on the 25th of November 1990. A second memorial was created for the 70th anniversary of the disaster, 27th November 2014.

Love local history? Support my work and uncover Stoke-on-Trent's stories here - https://linktr.ee/theredhairedstokie