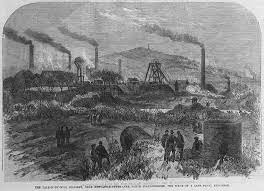

The history of coal mining in Staffordshire spans several centuries and has played a crucial role in shaping the county's economy and communities. Coal mining in Staffordshire can be traced back to Roman times when the region's coal resources were exploited to meet local energy needs. However, it was during the Industrial Revolution that coal mining in Staffordshire truly flourished, driving the county's growth and contributing to the nation's industrial development.

The Industrial Revolution and the expansion of the canal network in the late 18th century provided a significant boost to Staffordshire's coal mining industry. The county's rich coal deposits, particularly in the North Staffordshire Coalfield, made it a prime location for mining operations. The availability of coal-fueled the growth of industries such as iron and steel, pottery, and textiles, which were concentrated in towns such as Stoke-on-Trent and Wolverhampton.

During the 19th century, the demand for coal continued to increase, leading to the establishment of numerous collieries throughout Staffordshire. The workforce in the mines expanded rapidly, with thousands of men and boys working underground in hazardous conditions. These miners, often referred to as "pitmen," formed a significant part of the county's working-class population.

The mining techniques used in Staffordshire evolved over time. Initially, coal was extracted using primitive methods such as bell pits and drift mining, where coal seams near the surface were accessed. As the easily accessible coal was depleted, deeper mining methods, including shaft sinking and the use of steam-powered winding engines, became common. The introduction of more advanced mining machinery, such as coal-cutting machines and ventilation systems, further improved efficiency and safety in the mines.

The prosperity of Staffordshire's coal mining industry reached its peak in the early 20th century. However, the industry faced numerous challenges, including labour disputes, safety concerns, and the impact of two world wars. The decline of the coal mining industry began in the mid-20th century due to a combination of factors, including the discovery of alternative energy sources, changing economic conditions, and the depletion of easily accessible coal seams.

By the late 20th century, most of Staffordshire's coal mines had closed, marking the end of an era. The closure of the mines had a profound impact on the local communities, leading to unemployment, social upheaval, and the loss of a once-thriving industry that had been deeply intertwined with the region's identity.

Today, the legacy of coal mining in Staffordshire is evident in the landscape, with abandoned mine shafts and spoil heaps serving as reminders of the industry's past. Efforts have been made to preserve and interpret this heritage, with mining museums and heritage sites offering insights into the lives and experiences of miners. The mining industry's decline has also prompted the diversification of Staffordshire's economy, with a focus on sectors such as services, tourism, and advanced manufacturing.

While coal mining in Staffordshire is no longer a significant economic force, its impact on the county's history, culture, and communities is indelible. The legacy of coal mining serves as a testament to the resilience and hard work of the miners who toiled underground and the importance of acknowledging their contributions to Staffordshire's development.

However, with its immense risks and unforgiving nature, mining also holds a sombre legacy of disasters that have claimed countless lives and left lasting scars on the communities of the county.

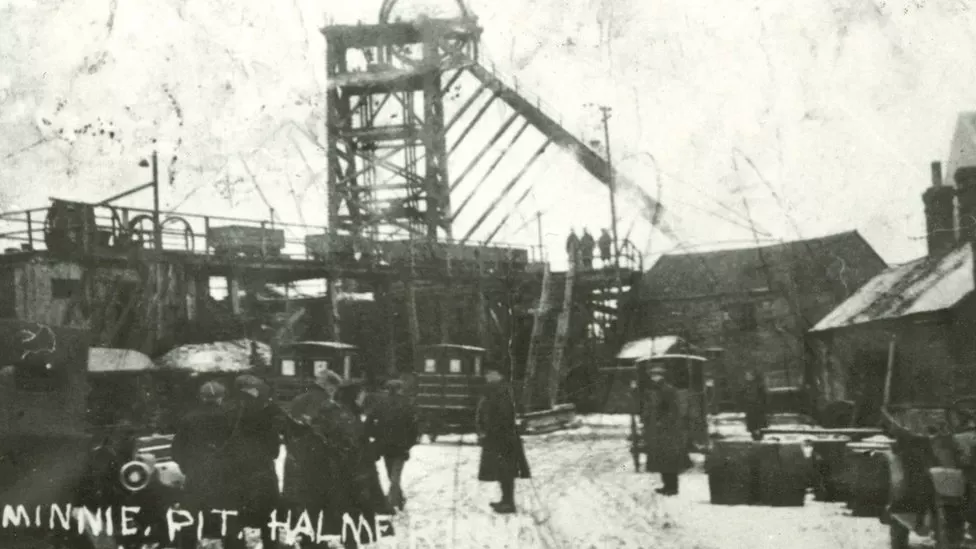

The Minnie Pit Disaster (1918):

The Minnie Pit disaster was a tragic accident that occurred on January 12, 1918, in Halmer End, Staffordshire. It resulted in the loss of 155 men and boys, making it the deadliest mining disaster in the North Staffordshire Coalfield's history. The exact cause of the ignition of flammable gases in the mine remains unknown, as no official investigation was able to establish the source.

The Minnie Pit colliery, named after Minnie Craig, the daughter of one of the owners, was established in 1881 in Halmer End. It was known for its profitability due to the mining of five thick seams of high-quality coal. The colliery served as the downcast shaft for the Podmore Hall Colliery, which was part of a larger industrial complex including an ironworks, forge, and coking ovens at Apedale. The Podmore Hall Combine, including the Minnie Pit, was later formed into the Midland Coal, Coke and Iron Company Ltd. The mining operation was accompanied by its own mineral railway, the Apedale and Podmore Hall Railway.

Despite its profitability, the Minnie Pit colliery had a history of danger due to the presence of firedamp, a mixture of flammable gases. Before the 1918 disaster, two other explosions had occurred at the colliery in 1898 and 1915, resulting in the loss of pit ponies and nine miners, respectively. However, these previous incidents had lower death tolls due to their occurrence on Sundays when fewer workers were present. The prevalence of firedamp also affected other collieries within the Podmore Hall Combine, leading to several explosions at the Burley Pit.

During World War I, coal mining played a vital role in supporting the country's needs, fueling ships, power stations, coke ovens, and the munitions industry. Many individuals working in the mines were either too young or too old to enlist in the military.

The disaster struck on January 12, 1918, when a massive explosion tore through the Bullhurst and Banbury Seams of the Minnie Pit. Within minutes, 155 workers succumbed to the effects of the explosion, roof collapses, or poisonous gases. Rescue efforts were immediately launched, with rescue teams from across the North Staffordshire Coalfield mobilized to search for survivors. Tragically, one member of the rescue team, Hugh Doorbar, lost his life during the operation, bringing the final death toll to 156. Among the victims, 44 were boys under the age of 16.

The explosion caused extensive damage to the underground workings, and the recovery process took 18 months to retrieve all the bodies from the pit. An investigation was conducted under the Coal Mines Act 1911, but it did not determine the exact cause of the initial flame. The jury's verdict attributed the cause of death to the explosion of gas and coal dust and highlighted the need for the systematic removal of coal dust to mitigate the extent of future explosions. However, no individual was held responsible for the disaster.

The Minnie Pit disaster had a profound impact on the mining community of Halmer End and neighbouring villages, as many families relied on the colliery for their livelihoods. The loss of lives and the closure of the pit during the Great Depression plunged the area into economic hardship. Relief efforts were initiated by the Miners Federation of Great Britain, and financial assistance was provided by various sources, including compensation from the Podmore company.

In the early 1980s, a memorial was erected by the National Coal Board and the local council to honour the victims of the disaster. The memorial serves as a lasting reminder of the lives lost in the pursuit of coal extraction at the Minnie Pit Colliery from 1890 to 1931.

The Talke o' th' Hill Disaster (1866):

The Talke o' th' Hill Colliery, situated in the Parish of Talke and owned by the North Staffordshire Coal and Iron Company, had two shafts. Both the downcast and upcast shafts measured 11 feet in diameter. The initial workings were reached at a depth of 160 yards in the Ten Foot seam, employing around 20 men.

The air intake for this area measured 5 feet 6 inches by 7 feet and was assessed by Mr Wynne, the Inspector, in November. Fourteen or fifteen men worked there, and no complaints were raised by the workers to the Inspector. The longest stretch of the workings extended 500 yards from the shaft, with each section being ventilated by a furnace.

At 5 a.m. on Thursday, a loud explosion and flames rushed up the shaft, covering the surrounding area with soot. The shock was felt half a mile away. Approximately 150 men were working in the pit at the time. Initial reports suggested that around one hundred lives had been lost.

Concerned onlookers gathered at the pit, impeding rescue efforts. The colliery manager, Mr Johnson, cleared the pit bank, and the cages descended into the mine. Fifty terrified boys were brought up the No.2 shaft, and several others were brought up the No.1 shaft, although they had suffered burns. The rescued individuals were revived with brandy. The injured were attended to by Messrs. Barnes Bruce and Greatorex, while the Reverend M.W.M. Hutchinson, the incumbent of Talke, provided comfort to the affected families.

Numerous teams of workers descended into the pit, but they encountered a very damp atmosphere. Many of the men who had been rescued from the No.2 shaft volunteered to return below. The bodies were found dismembered, with several of them lacking heads. Forty-three miners were found dead, and thirteen were injured. It was estimated that there were still 40 to 50 individuals trapped in the pit. The stables had caught fire, resulting in the deaths of 7 or 8 horses. The recovered bodies were washed and then identified by their grieving loved ones.

The cause of the explosion has never been found, but it was probably one of three things, firing shots, smoking, or removing the top of a lamp.

The Sneyd Colliery Disaster (1942):

The Sneyd Colliery Disaster, which occurred on 1 January 1942 in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, was a tragic coal mining accident. At 7:50 am, an underground explosion occurred when sparks from wagons ignited coal dust. The explosion claimed the lives of 57 men and boys.

Coal mining had been a longstanding activity in the Sneyd area of Burslem since the 18th century. Records from 1896 indicate that Sneyd No. 2 and Sneyd No. 3 employed a total of 609 men and boys underground, with 124 individuals working on the surface. In 1900, the company was officially registered as Sneyd Colliery. By 1940, the mine employed around 2,000 workers, but they faced a period of idleness due to the discovery of an underground fire. Previous incidents of deaths in the mine had occurred, including a fire in 1904 that claimed the lives of three workers.

Traditionally, miners refrained from working on New Year's Day due to an old superstition, but due to the demands of the war effort, the men of Sneyd reported for work as usual. At 7:50 am, an explosion erupted in the Banbury seam, located 0.5 miles (0.80 km) underground. The blast was powerful enough to knock men off their feet. Reg Grocott, a 16-year-old apprentice, was blown around a corner but saved by a water drum, while his coworker tragically lost his life after being thrown against a wall.

The explosion was confined to one coalface in the Banbury Seam of No. 4 pit, where 61 men were working. Four of them managed to escape alive. Other areas of the mine remained unaffected, but all miners were evacuated from the No. 2 pit and the rest of the No. 4 pit. The immediate aftermath saw the death of 55 workers, with two injured men later succumbing to their injuries in the hospital.

News of the explosion quickly spread, and anxious wives and relatives gathered at the pithead, awaiting updates. On the first day of rescue operations, 16 bodies were recovered before the presence of afterdamp forced a temporary halt to the efforts. At that point, it was announced that no further survivors were expected. The initial rescue team, the Sneyd Mines Rescue Team, was soon joined by additional teams from other collieries in North Staffordshire, including Black Bull, Chatterley Whitfield, Hanley Deep, and Shelton.

In the aftermath of the disaster, a fund was established, and many individuals, including soldiers stationed as far away as Iceland, contributed money. The final death toll of 57 left 32 widows and 35 fatherless children. Additionally, the 24 unmarried men who perished left behind eight widowed mothers and 13 grieving parents.

The subsequent inquiry, led by Sir Henry Walker, revealed that the derailment of tubs used to transport coal had damaged an electric cable, leading to sparks igniting coal dust and causing the explosion. However, some historians have contested this explanation in recent times, attributing the blame to a snapped steel cable that sparked. Another theory suggests that descending empty tubs collided with a compressed air pipe, causing a billowing of dust that was subsequently ignited by a spark. It is claimed that the cable was tested and proven to be safe.

The underground connection between Sneyd Colliery and Wolstanton Colliery led to coal gradually being extracted from Wolstanton instead of Sneyd. The colliery at Sneyd eventually closed down in the 1960s. In 2007, a memorial featuring a pit wheel was erected in Burslem town centre, bearing a plaque listing the names of all 57 victims.

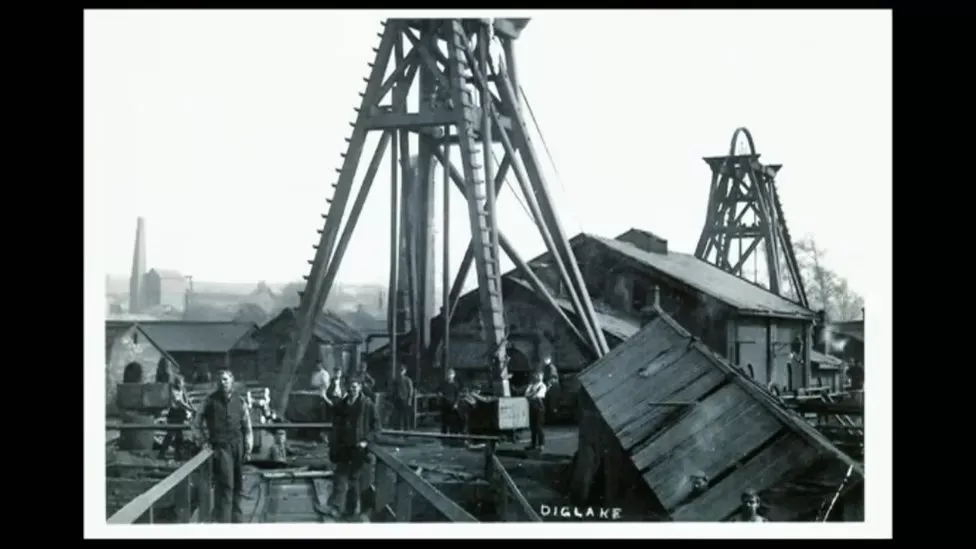

The Diglake Colliery Disaster (1895):

The Diglake Colliery Disaster, also known as the Audley Colliery Disaster, occurred on 14 January 1895 at what was Audley Colliery in Bignall End, North Staffordshire. A devastating flood of water inundated the mine, resulting in the loss of 77 miners' lives. Despite rescue efforts, only three bodies were recovered, and 73 miners remain entombed underground.

Diglake Colliery was situated in the village of Bignall End, Staffordshire. Mining activities had been carried out intermittently from 1733 until 1854 when the mine was abandoned due to the lack of a canal or railway connection, which made coal transportation unprofitable. In the 1890s, a new mine, known as Audley Colliery, was established near the old workings. It comprised three shafts: No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3, with depths of 790 feet, 745 feet, and 460 feet, respectively. The No. 3 shaft had previously been part of the Boyles Hall Colliery operations.

Audley Colliery was located east of the former Audley railway station on the North Staffordshire Railway line. The opening of the railway in 1870 made coal transportation more economically viable than in previous ventures. The precise separation distance between the new and old mine workings, referred to as Old Rookery Pit, was unknown due to incomplete records. Although plans aimed for an 80-yard separation, discrepancies in scaling measurements suggested a much narrower gap. Heavy rain and snow had overwhelmed the underground reservoir in the old Diglake Colliery adjacent to Audley Colliery, saturating the ground.

Between 11:30 and 11:40 am on 14 January 1895, while approximately 240 to 260 miners were underground, a massive wall of water forcefully entered the mine. It is believed that fireman William Sproston had ignited a shot in the new 10-Foot seam in Shaft No. 1, weakening the barrier between the new and old workings that were flooded with water. Modern estimates suggest that the water barrier was subject to a pressure of 100 pounds per square inch before it gave way.

Seventy-seven men and boys working underground were tragically drowned in the sudden influx of water. One of the fireman's sons, who happened to be on an errand for his father, was swept away by the waves but managed to escape with other miners through a shaft connecting to the disused Boyles Hall Colliery. William Sproston and his other son lost their lives in the deluge. Pumps installed in the mine were operational, evacuating water at a rate of 180 imperial gallons per minute, but the water level only decreased by 6 inches by the following day. Four days later, over 20 tonnes of water poured into the mine every minute.

Upon hearing the water rush and sensing the rising levels, under-manager William Dodd, who had an office at the bottom of the No. 2 shaft, swiftly alerted other miners to the danger and participated in the rescue of approximately 35-40 individuals. Dodd also organized a search party and re-entered the mine in an attempt to find survivors.

The next day, a roll call revealed that approximately ninety men were possibly still trapped inside the mine. A rescue team ventured as far as they could safely go but found no signs of life or any recovered bodies. Eleven days after the disaster, the water level dropped by 4 feet 4 inches in the old Rookery workings, the initial source of water influx. However, water continued to fill up the shafts at Diglake/Audley, revealing that the depth of all the old workings was less than anticipated, hindering the draining of floodwater.

Six months later, an inquiry concluded that no blame could be assigned to the mine owners but emphasized the need for better mine planning and accurate record-keeping of previous workings. Queen Victoria approved the awarding of the Albert Medal to William Dodd for his bravery during the disaster.

The official death toll stands at 77, although numbers like 78 and 80 have been mentioned due to a duplication error on a memorial. Notable concert pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski donated the proceeds from his concert in Hanley in 1895 to the Diglake Colliery Disaster Fund. In February 1895, three men involved in the rescue efforts, along with a rescued boy, appeared at the Canterbury Music Hall in London to raise funds for a widows and orphans appeal.

Coal mining operations at Diglake/Audley likely ceased after the disaster, although the exact timeline is unknown. A 1924 map depicts the colliery as disused. In 1932 and 1933, bodies were discovered during coaling operations at an adjacent mine. Seventy-two bodies remain entombed in the sealed-up mine workings.

In 1979, The Mines (Precautions Against Inrushes) Regulations mandated a minimum distance of 121 feet between shafts in new coal or mine workings to prevent collapse or flooding.

In 2013, plans for an opencast colliery on the site raised concerns about uncovering the miners' remains, although the company assured that they would not dig to the depth where the bodies were located. The application was eventually denied in 2014.

On the 125th anniversary of the disaster in January 2020, a sculpture depicting two kneeling miners was unveiled in the cemetery of Audley Methodist Church. The commemoration included a memorial walk and a minute's silence to honour the victims.

The Mossfield Colliery Disaster (1889):

Mossfield Colliery was located on the outskirts of Longton, at the southeastern end of the North Staffordshire Coalfield. The colliery had two shafts, both sunk to a depth of 440 yards, just below the Cockshead seam where the explosion occurred. This particular area was known as the 15s level, and other seams above and below the Cockshead seam were also worked from these shafts.

The colliery was owned by Messrs. Hawsley and Bridgewood Limited and was located near Longton in the Parish of Cavershall, Staffordshire. It had two shafts, situated fifteen yards apart, each with a diameter of ten feet six inches. Both shafts were used for coal extraction, with one cage descending while the other ascending. Each cage carried four tubs on two decks and operated on wire rope guides. The colliery had three working seams: the Hardmine at 250 yards, the Banbury at 363 yards, and the Cockshead at 414 yards. The shafts reached a depth of 440 yards to the hooking-on places near the bottom.

The Hardmine seam was connected to the upcast shaft at a hooking-on place in mid-shaft, while the Banbury and Cockshead seams were reached through a stone drift leaving the downcast shaft below the Hardmine seam. The Cockshead seam was worked using a panel system, with levels driven on the strike of the seam and excavations made between these levels, leaving ribs of coal. The Banbury seam was worked using the longwall system, where all the coal was removed in one operation. Tramroads were maintained on one or both sides of the drifts, and the ventilation in the pit was provided by a Waddle fan.

Safety lamps were used in both seams, but naked lights were used to light the bottom of the downcast shaft. The colliery officials included Mr J.G. Blackwell as the managing director, Mr James Potts as the certificated manager, and William Barker and William Fletcher as the underlookers. However, Barker and Fletcher had not been officially appointed in writing as required by the Coal Mines Act. The colliery operated in two shifts, employing around 200 people during the day shift and 100 during the night shift. Contractors and detailers worked separate shifts.

Before the explosion, there were indications of a potential gob fire, and the colliery had dealt with previous gob fires over the years. There had been ongoing problems and a lack of trust between Potts and Fletcher, with disagreements between them. Potts had recently been injured in an accident and had not been able to visit the pit regularly. When the gob fire was reported, it was believed that proper arrangements were not made to handle it, and stoppings were put in while the men were still working in the mine. There were also issues with ventilation, accumulation of gas, and supervision of the colliery.

The explosion occurred around 3:50 a.m., resulting in the loss of life and significant damage to the shafts and workings. Thirteen men in the Hardmine were safely evacuated, and assistance from neighbouring collieries arrived quickly to aid in the rescue and recovery efforts. The exploration of the mine revealed damage to timber, blown doors, and collapses. Sixty-four men and sixteen horses lost their lives in the explosion, with extensive damage to the Banbury and Cockshead seams. The recovery operations lasted over three months, but five bodies could not be recovered, and the exploration was limited due to gas and falls in the Cockshead seam.

Coal mining's importance in Staffordshire can be attributed to its role as a vital energy source, catalyst for industrial development, driver of economic growth, promoter of transport infrastructure, and agent of social transformation. The legacy of coal mining in Staffordshire continues to shape the region's history, heritage, and identity.

The coal mining disasters that occurred throughout Staffordshire's history have left a lasting imprint on the region. These tragedies serve as a stark reminder of the perilous nature of coal mining and the sacrifices made by the brave men who toiled underground. The stories of loss and resilience are a testament to the dedication and strength of the mining communities in Staffordshire.

Thank you for reading!

If you like what you have read, please feel free to support me by following and signing up for my newsletter and/or buying me a coffee!

Thank you.

I use the British Newspaper Archive to help with my research and you can sign up for a free trial here.

If you are interested in your local and family history, you can sign up for a free trial of Find my Past and access all archived local records and find your past.

If you are interested in the history of coal mining in Staffordshire then check out these books on Amazon.

Check out my recommended reading list