Blythe House, once a prominent estate and mansion in Blythe Bridge, Staffordshire, has largely faded from local memory, with its historical significance overshadowed by modern developments like the high school and library now occupying its former site. Its story though, is intertwined with some of the area's most influential people.

Watch my video on Blythe Hall on YouTube

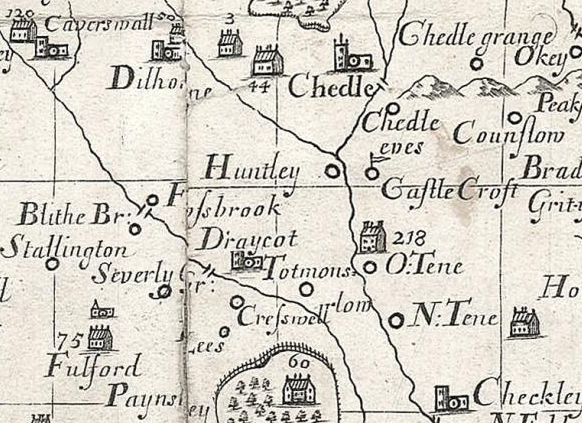

The region around Blythe Bridge in Staffordshire has a rich history that dates back to prehistoric times. Archaeological findings reveal that human activity in the area spans the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age, attracted by the fertile lands and the River Blithe. This river not only provided essential resources but also facilitated transportation and trade, making it a strategic location for early settlements.

With the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD, the area saw the introduction of roads and river networks that likely played a role in Roman logistics and trade. After the Romans, the area became part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia, and its name "Blythe," derived from the river, was established during this period. The Norman Conquest further transformed the region, with the Domesday Book of 1086 documenting local governance and land ownership changes that deeply affected the community. This historical backdrop set the stage for the later industrial development of Blythe Bridge and the construction of Blythe House in the 19th century, reflecting the ongoing economic and social evolution of the region.

The Industrial Influence and Rise of Blythe House

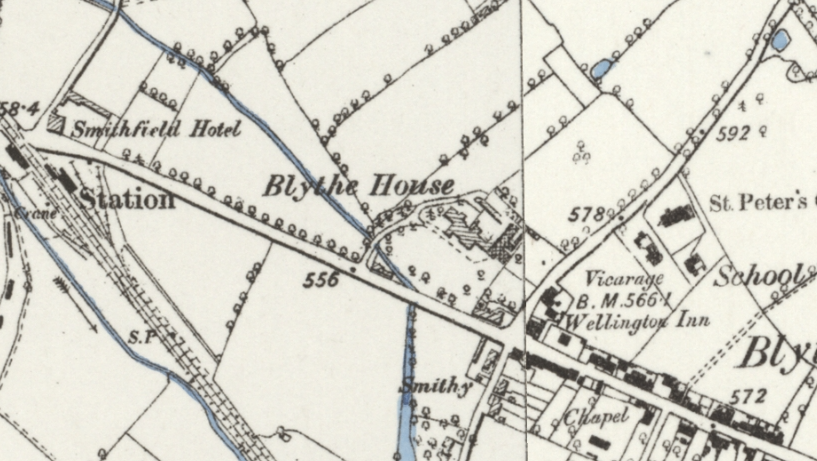

The 19th century marked a significant transformation for Blythe Bridge, largely fueled by the broader changes brought on by the Industrial Revolution. The establishment of the North Staffordshire Railway in 1848 was a pivotal development, turning the village into a crucial transport hub. This enhanced connectivity not only facilitated the movement of goods and people but also stimulated local industries. Proximity to Stoke-on-Trent, the heart of England's burgeoning pottery industry, was particularly beneficial, allowing for easier distribution of pottery products and access to raw materials.

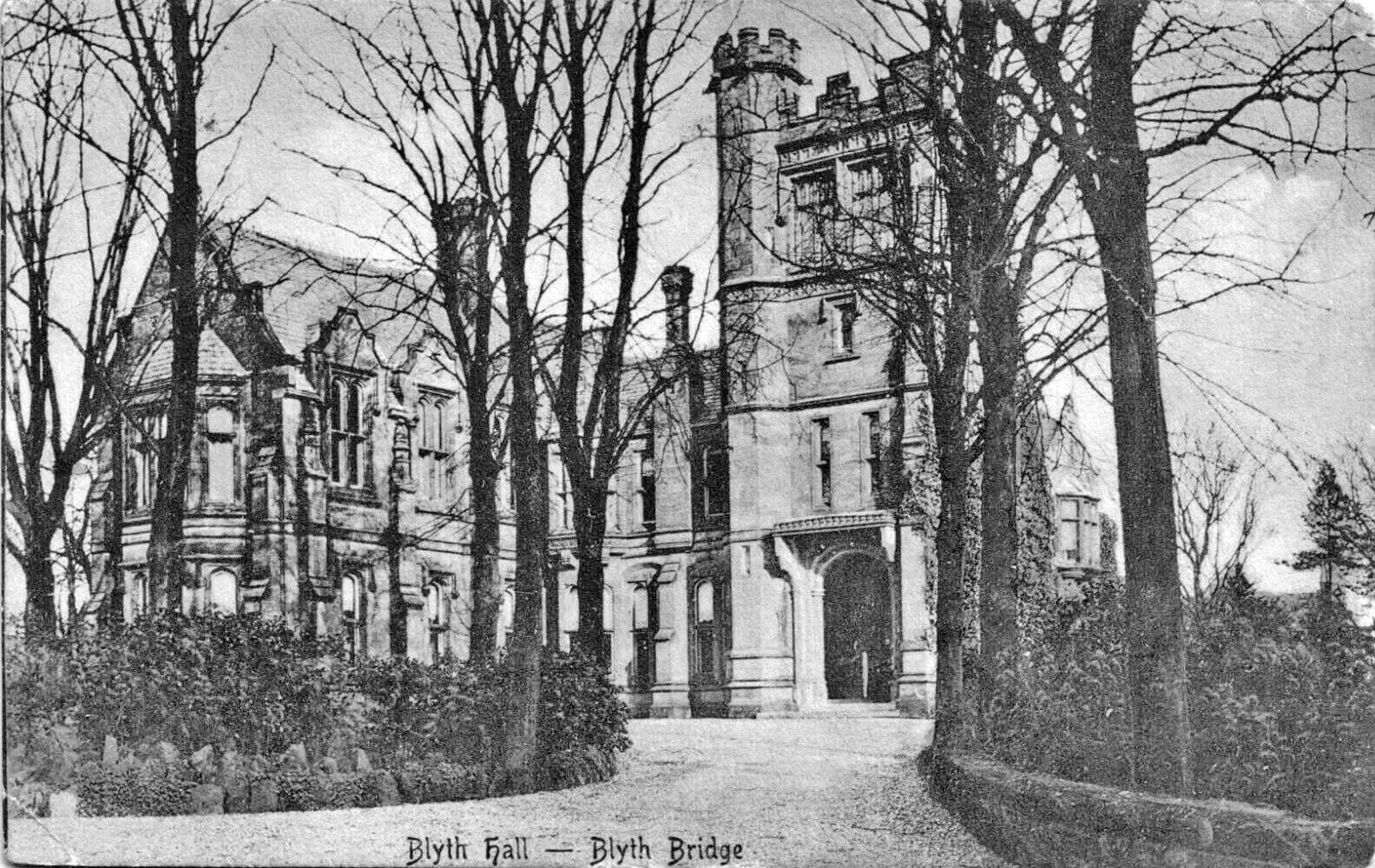

It was against this backdrop of industrial and economic growth that Charles Harvey, a prominent figure in the local pottery industry and a respected banker, decided to build Blythe House in 1853. The mansion was a splendid example of Victorian architecture, with features that not only added to the aesthetic appeal but also provided robust structural integrity to the building.

William Amery and the Charity Trust School

Before Blythe House was constructed in 1853, the site had a long-standing history of educational and communal use, dating back to the early 18th century. The land was originally designated for charitable and educational purposes under the will of William Amery, a local benefactor who played a significant role in the community of Blythe Bridge.

In his will dated August 26, 1728, William Amery left specific instructions for the use of his land. He bequeathed approximately seven acres of land, known as Pool Street Meadows, in the Parish of Dilhorne, to his wife for her lifetime. Upon her death, the land was to be used to build a schoolhouse and to support educational activities for the local children. Amery's vision was to provide free education to the children of the poor in the immediate locality, which was a forward-thinking initiative for the time.

Following the directions laid out in Amery's will, trustees were appointed to oversee the construction and management of a schoolhouse on the site. This Charity Trust School was built to serve as a grammar school, and by the early 1850s, it was teaching around 125 pupils the basic subjects of reading, writing, and arithmetic, commonly referred to as the "three R's.

The original schoolhouse that Amery's will had funded eventually fell into disrepair, and by the early 19th century, it was no longer in use. In response, new trustees re-administered the charity in 1809, leading to the renovation and reopening of the school several years later. However, by the mid-19th century, the needs of the community and the conditions of the building led to the closure of the original grammar school. A new school was then built on a different part of the site.

Transition to Blythe House

With the original educational use of the land concluded and the new school established elsewhere, the site was available for new development. It was at this point that Charles Harvey acquired the land and built Blythe House, transforming the site from its educational origins to a private residential estate. This change marked a significant shift in the use and status of the land, aligning it with the economic and social expansions of the Industrial Revolution.

Thus, the site that Blythe House occupied had a rich history of serving the educational needs of the community, rooted in the philanthropic bequest of William Amery. His legacy of supporting local education laid the foundational use of the land, which continued to evolve with the changing needs and fortunes of Blythe Bridge.

Architectural Features and Layout of Blythe House

Blythe House was a quintessential example of Victorian architecture, embodying the era's penchant for grandeur, elaborate detailing, and substantial domestic provisions. The estate's design and facilities highlighted the affluence and social status of its owners, making it a landmark in Blythe Bridge.

Exterior Features

- Structure: The mansion's architectural style was distinguished by its robust, buttressed walls, which not only provided structural support but also added a dramatic aesthetic with their imposing appearance.

- Windows: Bay windows were a prominent feature, offering expansive views of the surrounding landscapes and allowing natural light to flood the interior spaces. These windows also served as cosy, sunlit nooks ideal for reading or enjoying the garden views.

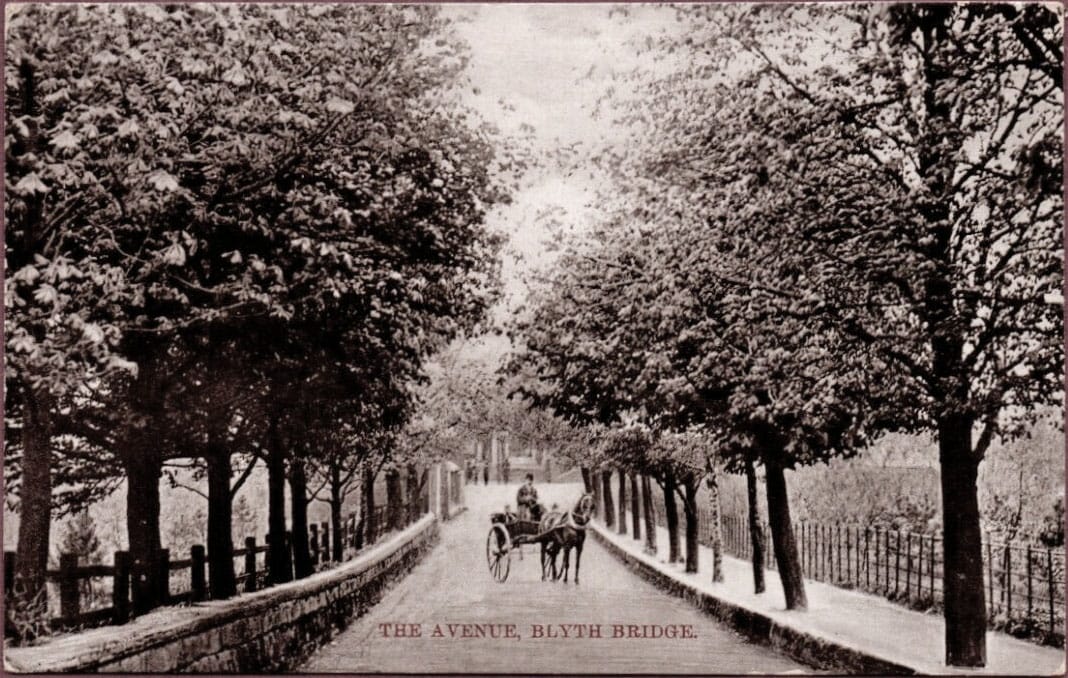

- Gardens and Grounds: The house was set in a meticulously landscaped 16-acre garden, which included manicured lawns, ornamental trees, and flower beds. The gardens were a vital aspect of the estate, designed for leisurely walks and outdoor gatherings.

- Outbuildings: Accompanying the main structure were several outbuildings, including stables for horses, a coach house for carriages, and additional service quarters for gardening and maintenance equipment, highlighting the comprehensive functionality of the estate.

Interior Design

- Entrance Hall: Guests entering Blythe House were greeted by a grand entrance hall, which set the tone for the opulence that defined the rest of the home. This hall was typically adorned with ornamental furniture, rich tapestries, and artworks, making a statement of wealth and taste.

- Reception Rooms: The house featured several reception rooms, each tailored for specific social functions:

- Morning Room: Used primarily in the morning as a casual sitting room, often bathed in sunlight, perfect for informal family gatherings.

- Dining Room: Designed for formal dining, this room was likely equipped with a large dining table and fine china, reflecting the owner’s status and hospitality.

- Drawing Room: A more formal sitting room used for entertaining guests, decorated with plush seating and exquisite decor.

- Service Areas: The dual kitchens facilitated both everyday cooking and larger gatherings, supported by a well-stocked wine cellar, a larder for food storage, and a dairy. These areas underscored the estate’s self-sufficiency and the household’s capacity to host and entertain on a grand scale.

Upper Floor Layout

- Bedrooms: The upper floors housed seven bedrooms, each potentially decorated according to the Victorian tastes of the time, with heavy drapes, ornate furniture, and luxurious bedding. These rooms served the family and guests, providing comfortable, private spaces.

- Saloon and Linen Room: The saloon in Victorian homes was a common area for relaxation and informal entertainment, often luxuriously appointed. Adjacent to these areas, a linen room stored bedding, tablecloths, and other textiles, essential for the upkeep of a home of this stature.

Blythe House was not just a residence but a symbol of prosperity and industrial success, reflecting the new wealth of England's industrial magnates.

Owners of Blythe House: Profiles and Contributions

The history of Blythe House, once a significant estate in Blythe Bridge, Staffordshire, is closely tied to the notable individuals who owned and inhabited it throughout its nearly a century-long existence. Each owner brought their influence to the property, leaving behind a legacy of both prosperity and decline.

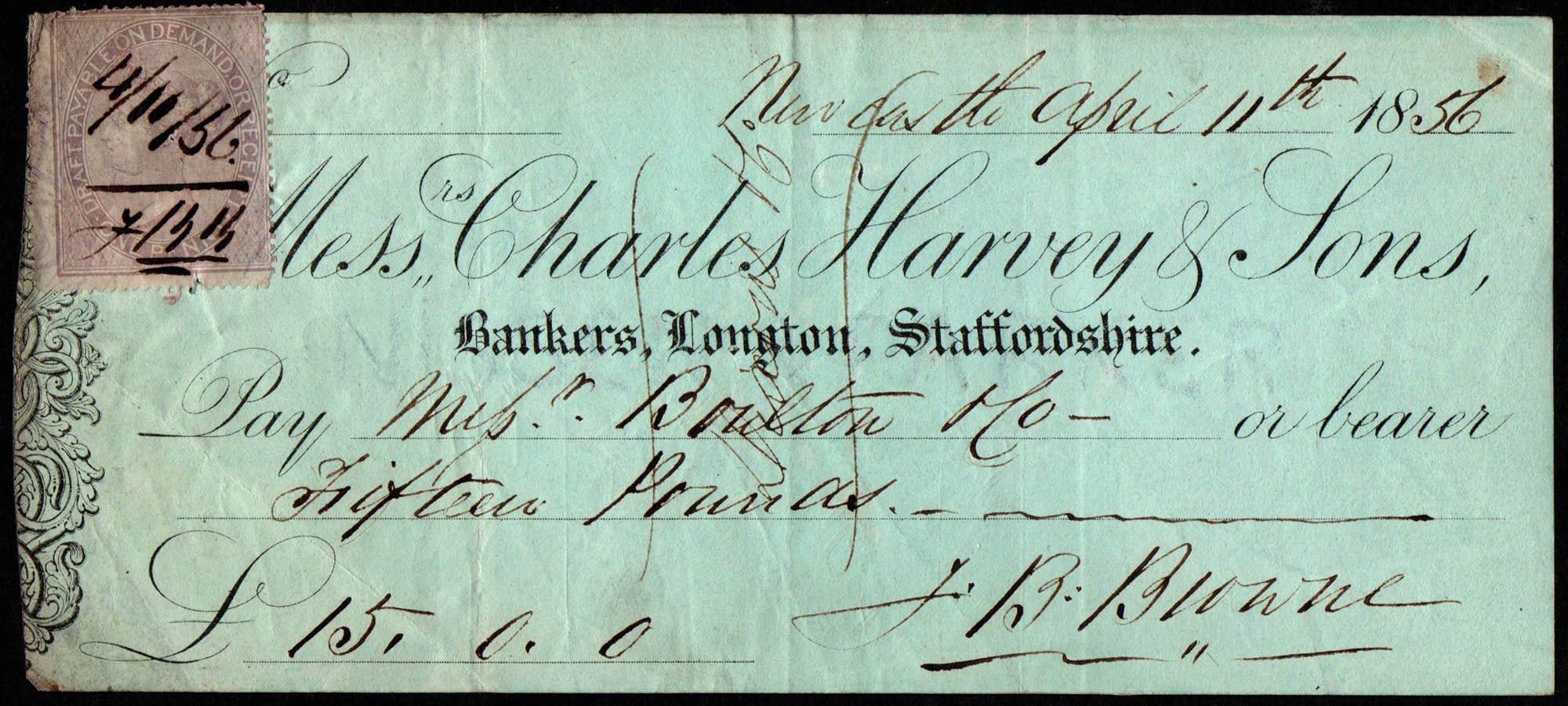

Charles Harvey: The Founder

Charles Harvey was a central figure in the industrial growth of Blythe Bridge, Staffordshire, during the mid-19th century. As a prominent pottery manufacturer and banker, Harvey exemplified the entrepreneurial spirit of the Industrial Revolution. Alongside his son, William Kenwright Harvey, he operated the Stafford Street Works in Longton from 1835 until 1853, under the business name C & W K Harvey. Their success is evidenced by their ownership of three pottery factories in Longton by 1841, demonstrating significant expansion and influence in the local pottery industry.

The Harveys specialized in producing a variety of pottery goods, likely including the typical range of Staffordshire pottery: tableware, decorative pieces, and perhaps sanitary wares, which were becoming increasingly popular at the time. The quality and variety of their products would have been crucial in establishing their reputation and enabling them to stand out in a competitive market. In 1853, using his wealth from pottery and banking, Harvey built Blythe House, a grand mansion that reflected his status and the industrial prosperity of the era.

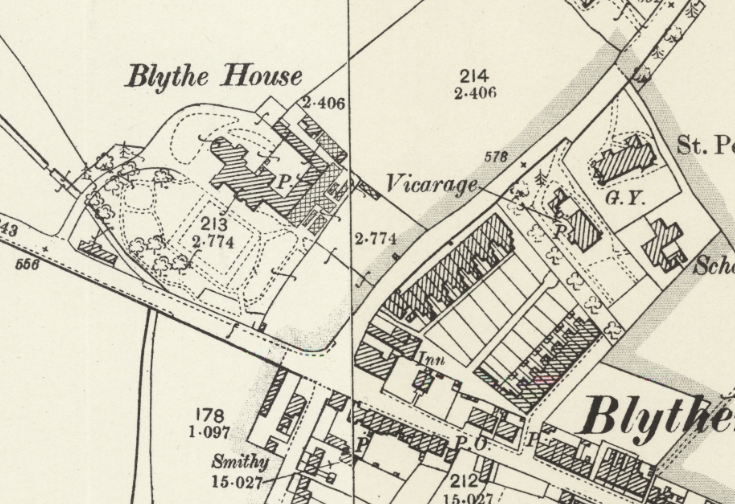

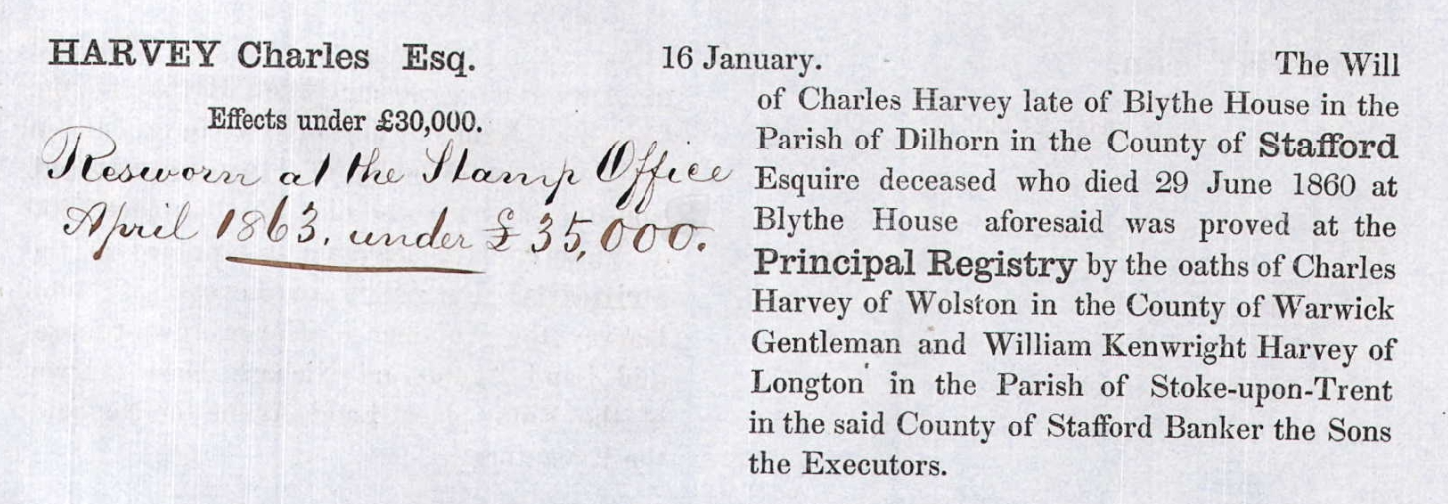

Charles Harvey was not only a prominent figure in the pottery industry of Stoke-on-Trent but also a key player in the banking sector in Longton, where he established a private bank alongside his pottery business. His bank played a crucial role in the local economy, offering financial services such as loans, savings accounts, and financing for local industrial projects, which were vital during the Industrial Revolution.

After Charles Harvey died in 1860, the bank faced challenges under the management of his son, William Kenwright Harvey, whose financial mismanagement led to significant difficulties for the bank. In 1866 Harvey's bank was absorbed by a larger institution, the Birmingham District and Counties Bank, as part of a trend towards consolidation in the banking industry to ensure stability and growth.

The Birmingham District and Counties Bank, which later became known as the United Counties Bank, was eventually taken over by Barclays Bank. This series of mergers and acquisitions reflects the broader trends of the 19th-century banking industry in Britain, where many small private banks merged into larger entities to cope with economic fluctuations and to expand their reach. Through these transformations, Charles Harvey’s initial banking venture ultimately became part of Barclays, linking his local financial activities to a global banking name.

Charles Harvey's death in 1860 marked the beginning of the decline of Blythe House. The younger Harvey's poor financial management led to substantial debts and the eventual loss of the family fortune. Despite this troubled end, Charles Harvey’s contributions to the local economy and the pottery industry had already cemented his legacy as a significant figure in the region’s history, setting the stage for its future development even beyond his era.

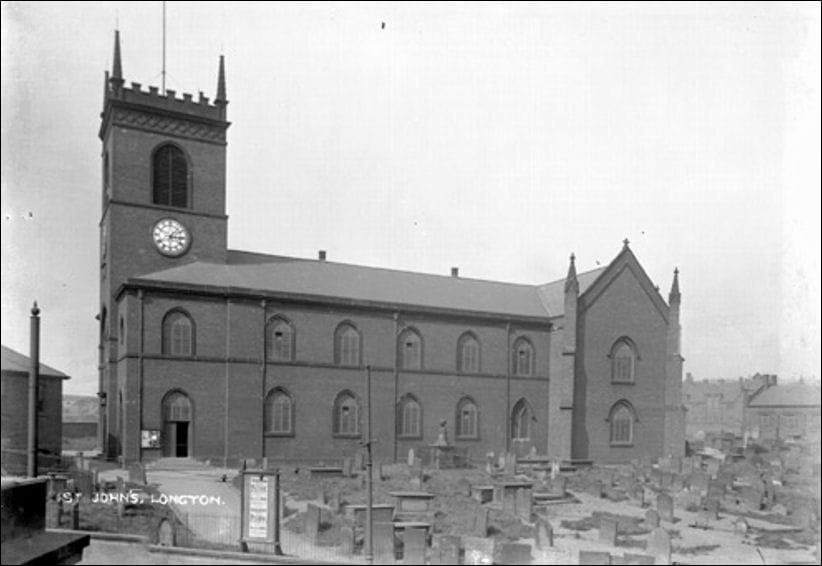

St John's Church and the loss of Charles Harvey's Memorial

St. John's Church in Longton, where Charles Harvey was laid to rest, was an important landmark in the community for nearly two centuries, being built in 1792. He was one of the original trustees for the expansion of the church in 1827. However, in 1979, this historic church was demolished due to mining subsidence, a problem endemic to the Staffordshire area, which has a rich but geologically disruptive coal mining heritage. The extensive mining operations beneath the town over the years weakened the ground, ultimately making the area prone to subsidence and rendering many old buildings unsafe, including St. John's Church.

With the demolition of the church, many memorials and inscriptions within were lost, including the one dedicated to Charles Harvey that was in the Lady Chapel. His memorial plaque, which commemorated his contributions to the local community as a prominent businessman and a respected local figure, was among those that could not be preserved.

His memorial read;

UNDERNEATH

LIE THE REMAINS OF

CHARLES HARVEY, ESQUIRE

OF BLYTHE HOUSE, STONE

BORN 3rd JULY, 1789 DIED 29th JUNE, 1860

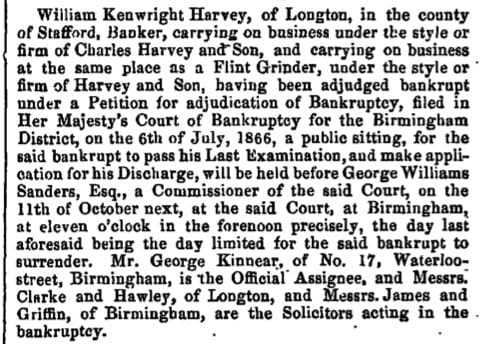

William Kenwright Harvey: The Downfall

William Kenwright Harvey's inheritance of Blythe House marked a significant turning point in the history of this grand estate. As Charles Harvey's son, William was bequeathed not only the physical property but also the responsibility for upholding his father's legacy in both the pottery industry and banking. Unfortunately, William lacked his father's business acumen and financial management skills, leading to a series of poor decisions that would ultimately tarnish the Harvey family's name and legacy.

Taking over the reins in 1860, William Kenwright Harvey initially tried to manage both the pottery operations and the family's banking business. However, his lack of experience and perhaps overconfidence led to risky financial practices. Unlike his father, who had successfully balanced the demands of a growing industrial enterprise with those of a private bank, William struggled to navigate the complex economic landscape of the time. His ventures began to haemorrhage money, exacerbated by broader economic pressures that were common in the mid-19th century, including market volatility and competitive pressures in both banking and pottery.

The Bank Scandal

The situation reached a crisis point when it was discovered that there was a significant amount of gold missing from the bank William managed. This scandal not only shocked the local community but also undermined confidence in the bank's stability. Rumours and accusations swirled, pointing to possible embezzlement or mismanagement by William as the cause of the missing funds. The scandal was a public spectacle, casting a long shadow over the Harvey family's reputable name.

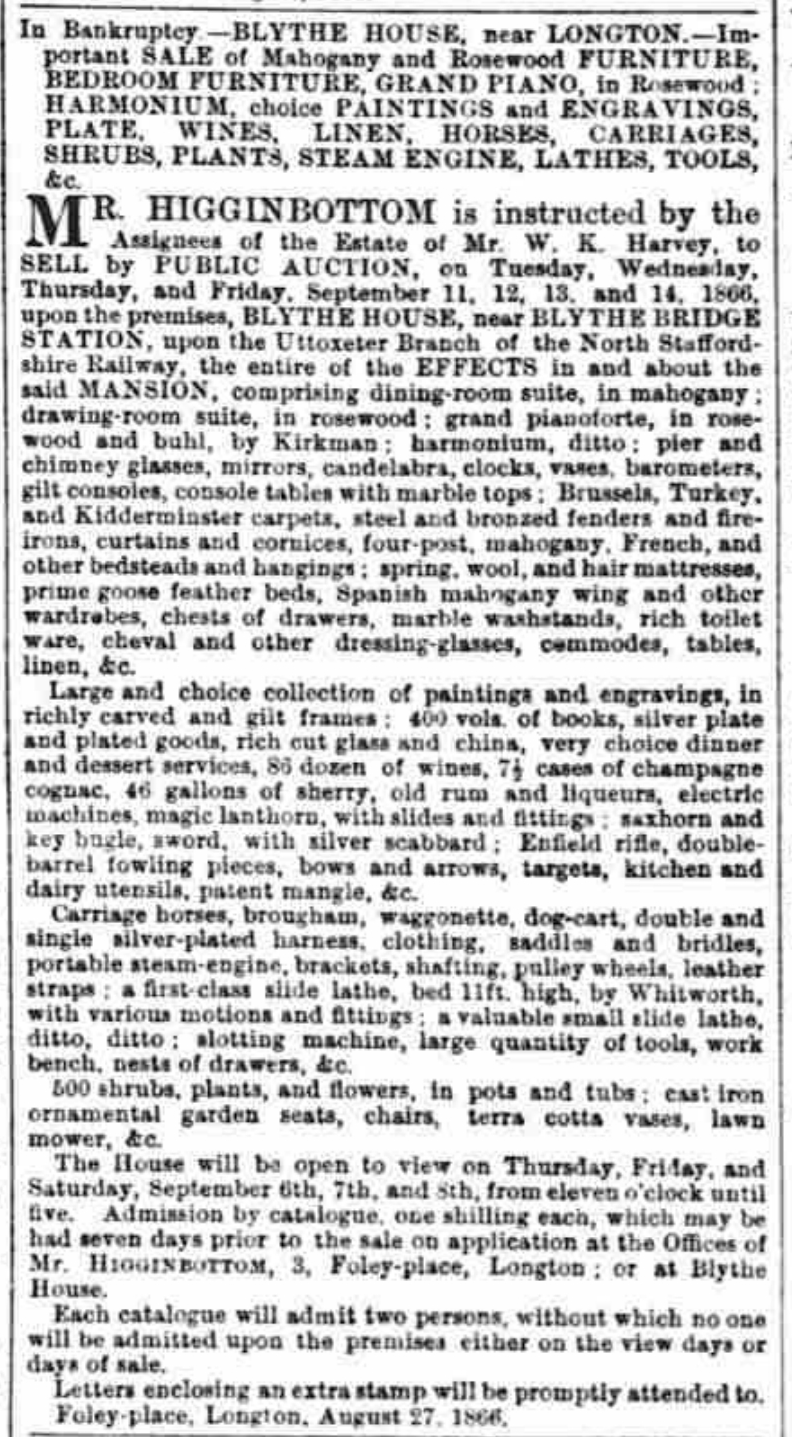

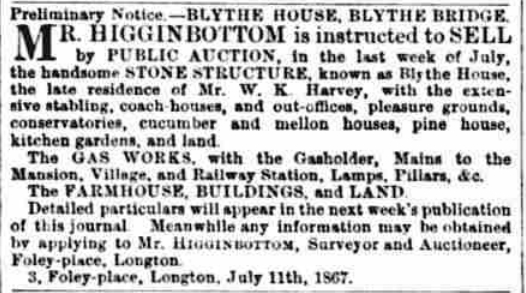

As the financial losses mounted, the Harvey estate, including Blythe House, could no longer sustain the economic burden imposed by William's mismanagement. In 1866, the same year as the gold scandal, the estate was forced into public auction as a means to settle the overwhelming debts accrued under William's control. This auction symbolized the tragic downfall of the Harvey family's fortunes and their association with Blythe House.

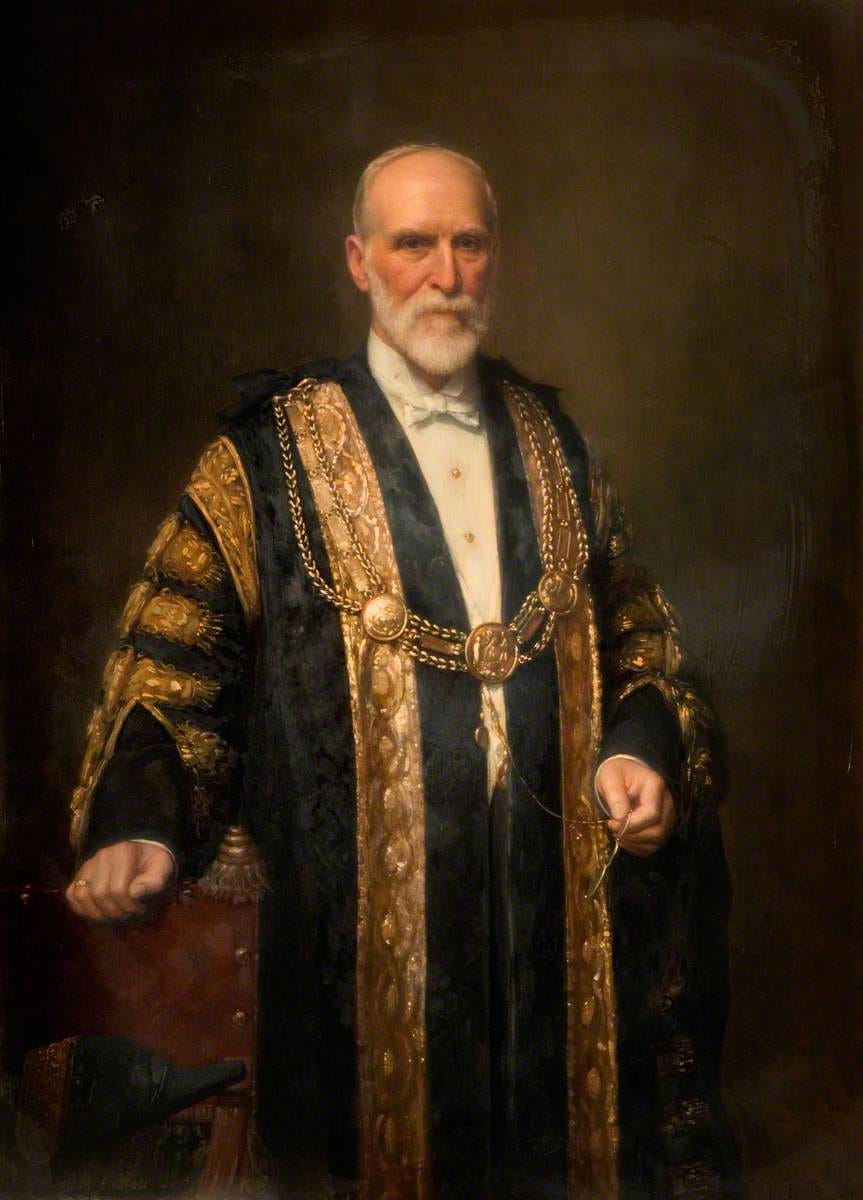

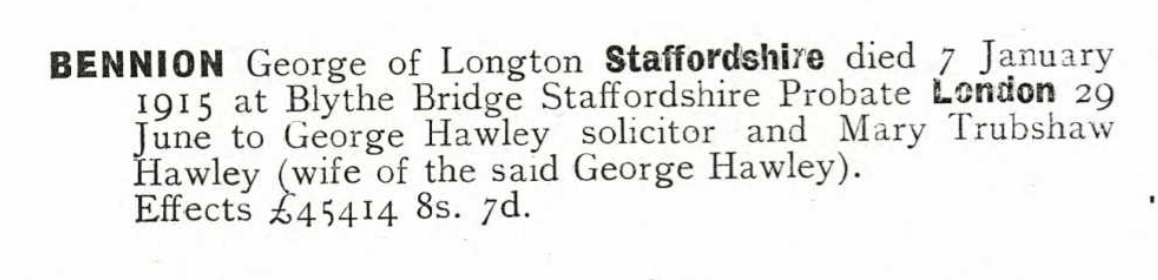

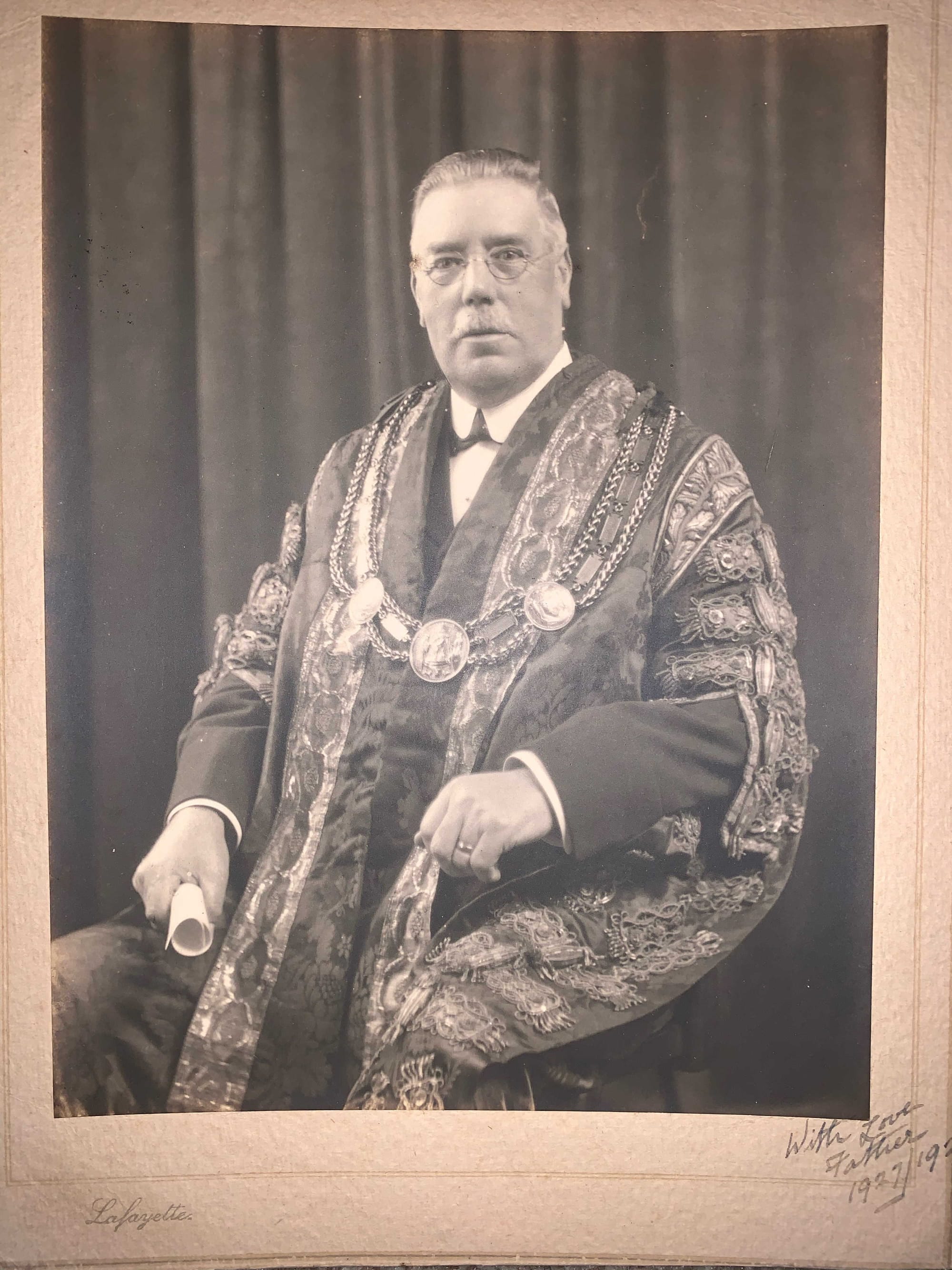

George Bennion: The Civic Leader

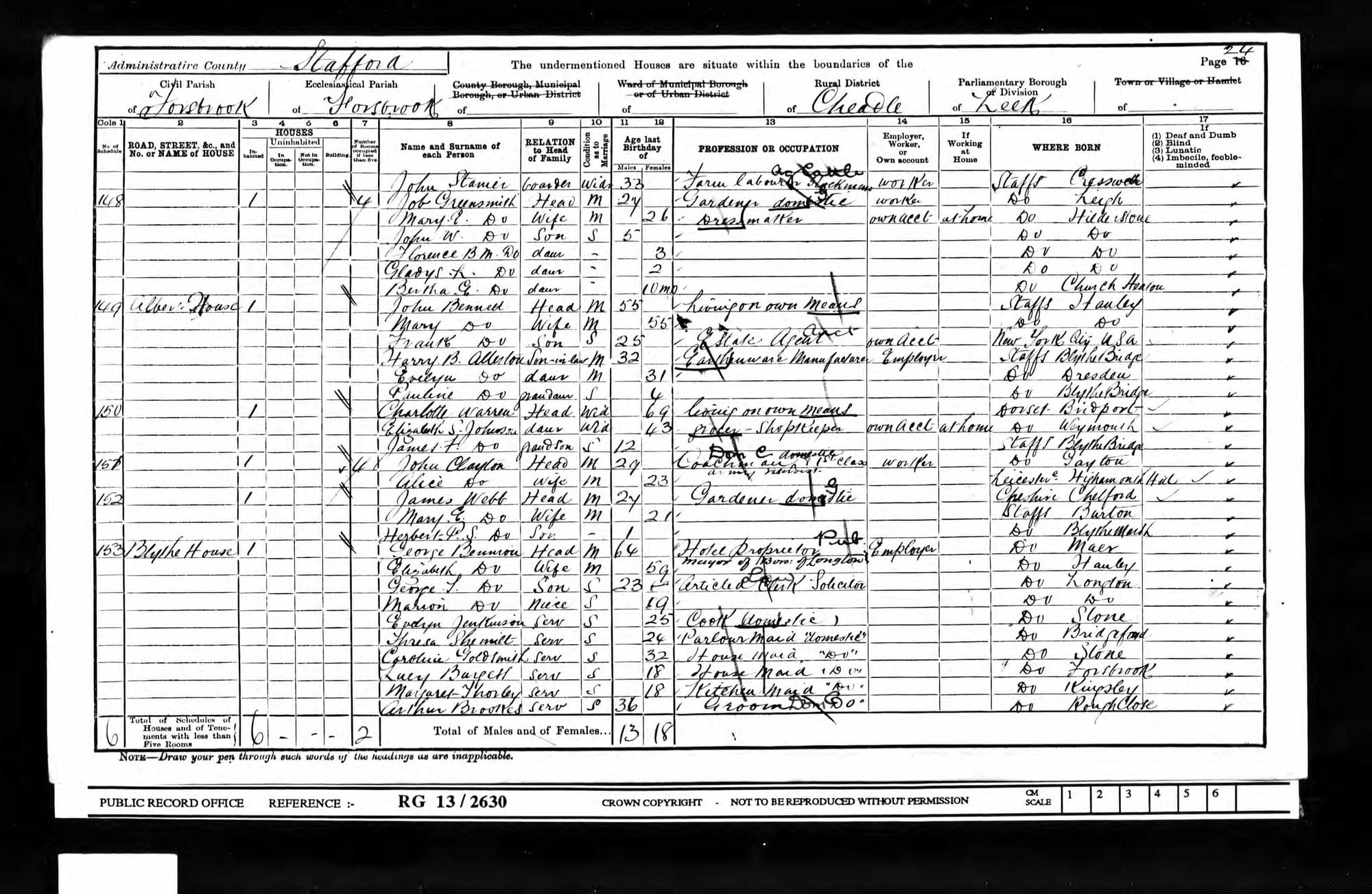

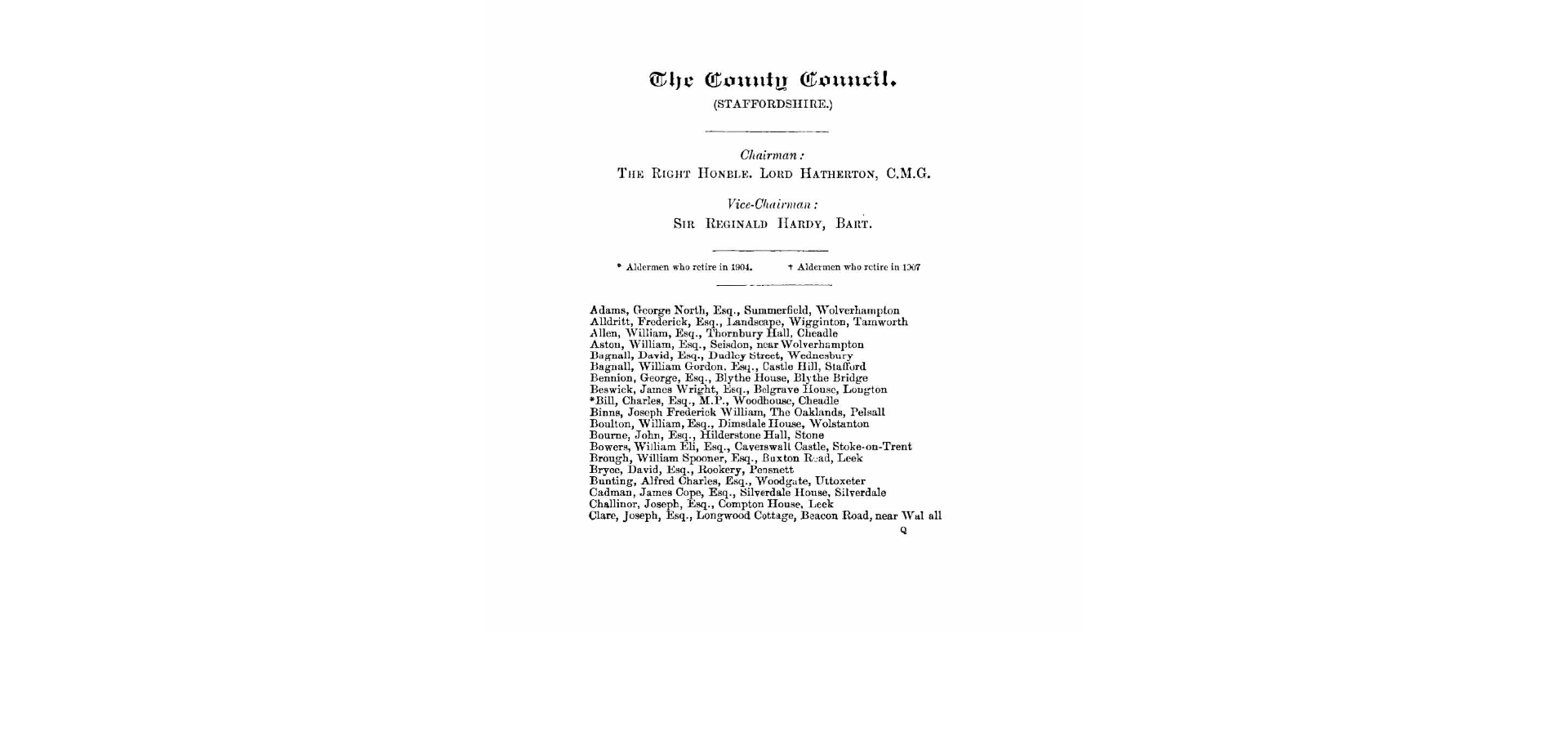

George Bennion, a figure of considerable repute in local governance, became the new steward of Blythe House after acquiring it at the public auction. Bennion's acquisition marked a new chapter for the historic property, which he aimed to restore to its former glory and integrate into the community life of Longton and Blythe Bridge.

George Bennion was well-known in the community for his extensive civic involvement, particularly in Longton, where he served as mayor four times. He was also the proprietor of Longton’s Crown Hotel, which at that time was an important and well-situated hotel. His repeated elections underscored the trust and respect he commanded in local society. His leadership style was characterized by a proactive approach to civic duties, focusing on public welfare and community development. His tenure as mayor coincided with a period of significant growth and change within the region, driven by the ongoing Industrial Revolution, which demanded thoughtful urban management and infrastructure development.

As the owner of Blythe House, Bennion extended his civic spirit to the estate itself. He was keen on stabilizing the mansion and its expansive grounds following the tumultuous period under William Kenwright Harvey. By restoring Blythe House, Bennion not only preserved a local architectural treasure but also reinforced its status as a symbol of community pride and history. He often used the mansion for public gatherings and social events, which helped integrate it into the social fabric of the area, making it a centre for local activities and celebrations.

Under Bennion's care, Blythe House regained its status as one of the area's premier estates. He maintained the property meticulously, ensuring that the gardens and outbuildings were kept in excellent condition. This attention to detail helped restore the house's reputation as a well-managed and beautiful place, erasing memories of its recent past marred by financial scandal and neglect.

Thomas Clarke Wild: The Potter and Philanthropist

Thomas Clarke Wild, renowned for his contributions to the English Bone China industry, notably through the Royal Albert brand, acquired Blythe House in 1916. His leadership in pottery manufacturing had already established him as a major industry player in Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, where he began his china manufacturing at Albert Works in 1893. Under his guidance, Royal Albert became synonymous with high-quality, intricately designed bone china, beloved both domestically and internationally.

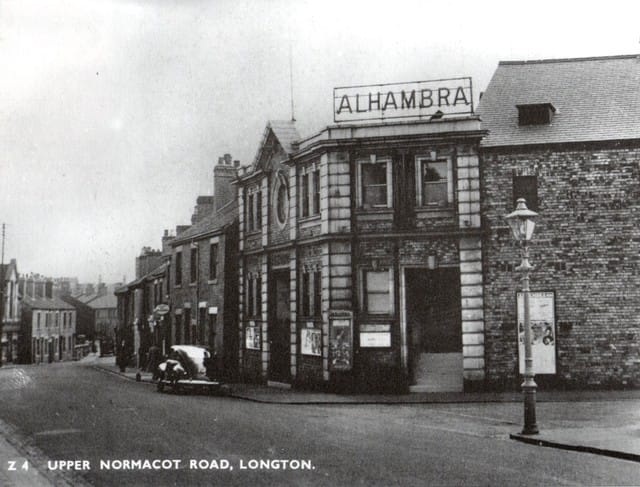

Alongside his achievements in pottery, Wild was a dynamic entrepreneur with diverse interests. In 1914, he expanded into entertainment by building the Alhambra Cinema in Longton, reflecting his commitment to enhancing local cultural life. This cinema not only served as a popular local venue but also underscored Wild’s role as a community benefactor and patron of the arts.

His civic engagement extended further when he served as the mayor of Stoke-on-Trent, a role that allowed him to influence local governance and public policy significantly. His tenure as mayor coincided with his years at Blythe House, during which he continued to promote prosperity and cultural enrichment in the community.

During his time at Blythe House, Wild's success in business allowed him to host and support various community events, making the mansion a social hub in the area. His philanthropy and involvement in local initiatives were well-regarded, and he used his resources to support the community extensively.

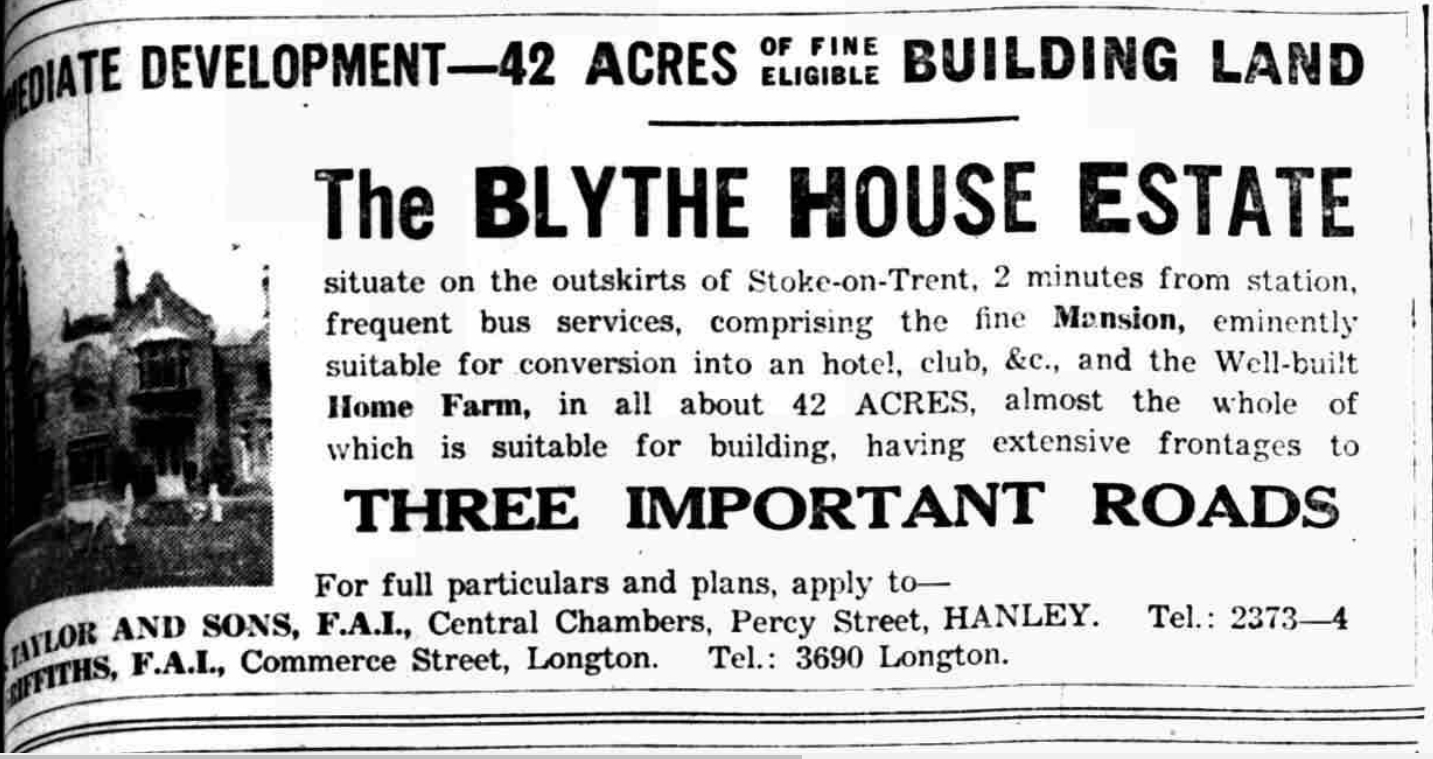

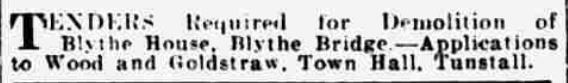

Wild resided in Blythe House until 1932. After he moved out, the mansion stood vacant and was eventually demolished in 1939, signalling the end of an era for the grand estate. Despite the demolition of Blythe House, Thomas Clarke Wild’s legacy in the pottery industry and his contributions to the Stoke-on-Trent community remained impactful. His diverse business interests, including his significant expansions and acquisitions in pottery manufacturing and his venture into cinema, left a lasting mark on the region. As a former mayor and a cultural patron, his efforts to foster community development and engagement helped shape the cultural landscape of Longton and beyond.

The Legacy and Its Disappearance

Blythe House, once a beacon of Victorian grandeur and a testament to the economic and social prowess of its various owners, has now largely faded from the collective memory of the public.

A stained glass window in St. Peter’s Church, Forsbrook, dedicated to the mansion’s first owner, Charles Harvey, remains the sole homage to its storied past, offering only a subtle hint at the grandeur that once characterized the area.

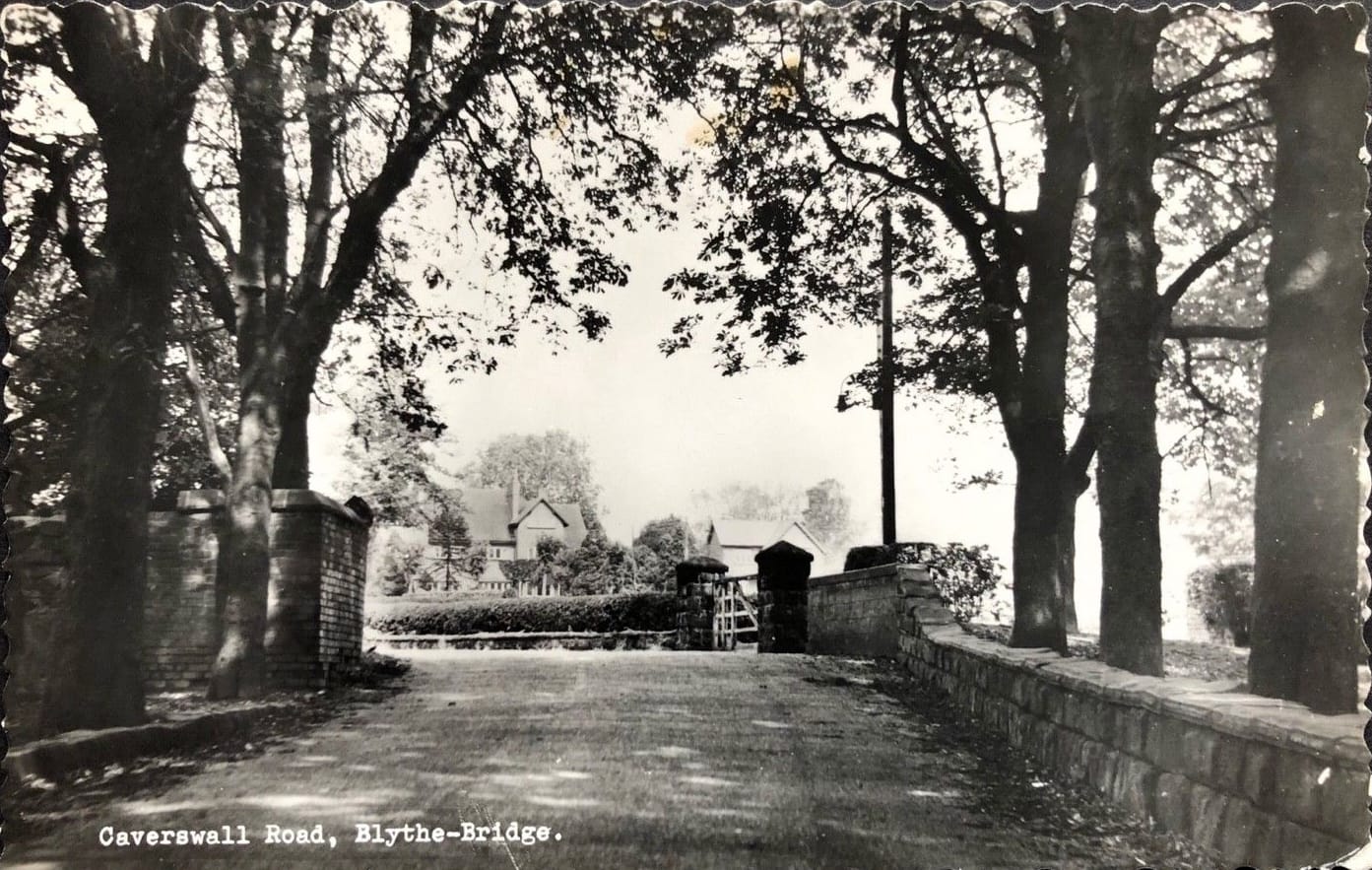

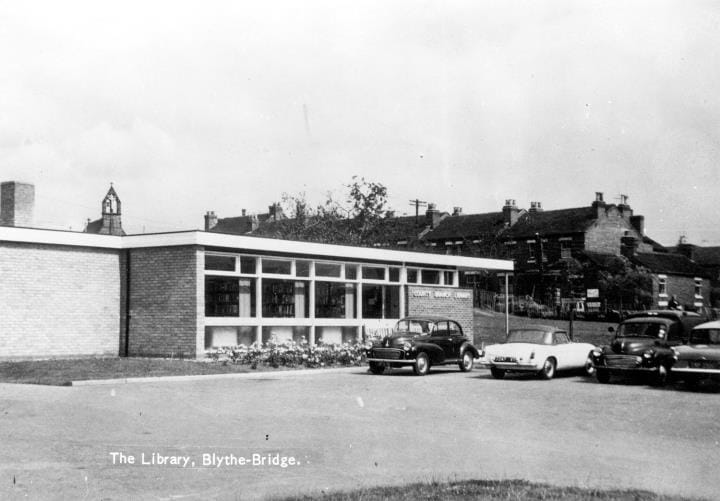

Despite its historical significance and the grandeur it once boasted, Blythe House was demolished in 1939. Today, the estate's rich history is largely unrecognized by the general public. The land where the majestic mansion once stood is now occupied by a high school and library, which serve vital educational and communal roles but have effectively replaced the physical evidence of the house's illustrious past. This transformation highlights a common narrative of progress overshadowing heritage, as modern utility supplants historical legacy.

Although Blythe House itself was demolished in 1939, not all traces of the estate have vanished completely. Subtle remnants still linger on the site, offering a faint glimpse into its storied past. Portions of the original boundary wall still stand, marking the periphery of what was once an expansive and grand property. Additionally, some of the gate posts that once heralded the entrance to the estate remain, standing as silent sentinels to history. These elements, though minimal, serve as physical links to the era of Blythe House's prominence, providing tangible connections to the history that the current educational and communal facilities have largely overwritten.

The tale of Blythe House is a poignant reminder of the impermanence of legacy in the face of relentless modernization, serving as a case study in the loss of cultural heritage to progress and redevelopment.

Thank you for reading!

If you like what you have read, please feel free to support me by following and signing up for my newsletter and/or buying me a coffee!

Explore a unique collection of Stoke-on-Trent and Staffordshire-themed art, photography and more at The Red Haired Stokie’s online shop. Discover my selection of locally inspired photographs, bespoke artwork, and original designs that celebrate the rich heritage and vibrant culture of the region.

https://www.theredhairedstokie.com

Check out my on-line shop for my local photography and art

Check out my recommended reading list