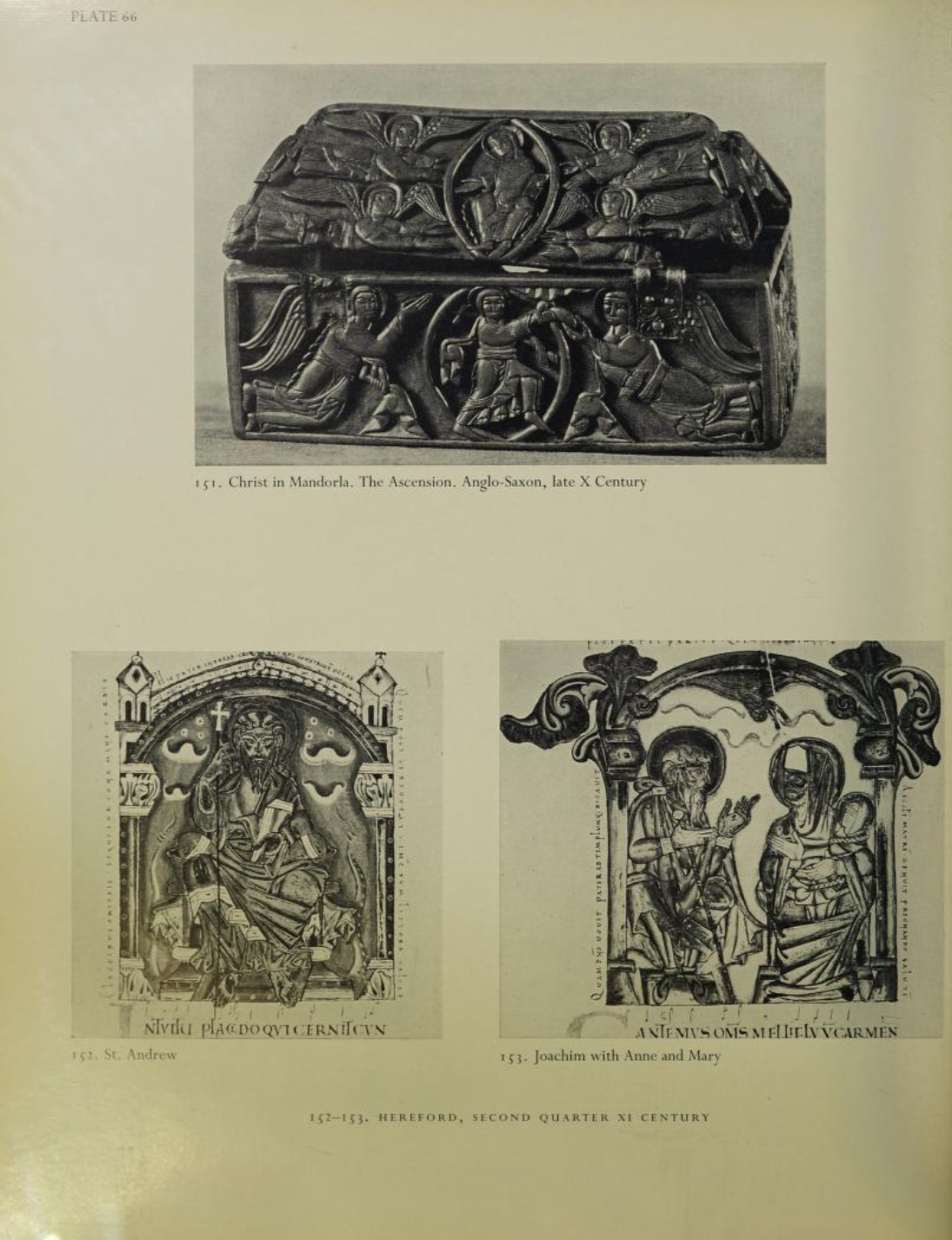

The Uttoxeter Casket, carved in England around 1050, is a rare and remarkable glimpse into the world of late Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship. This beautifully carved wooden artefact, now housed in the Cleveland Museum of Art, weaves together art, religion, and history in an object that feels almost timeless.

Crafted from boxwood, the casket is small but mighty, measuring just 15.7 cm in length, 7.8 cm in width, and 9 cm in height. Its detailed carvings depict key moments from the life of Christ, scenes such as the Nativity, Crucifixion, Baptism, Ascension, and Entry into Jerusalem. Each intricate carving tells a story, blending symbolism with stunning detail that reflects the artistry of its unknown maker. Likely created to hold sacred relics, this precious object would have taken pride of place in a church or monastery, a focal point of devotion and faith.

The journey of the Uttoxeter Casket is just as fascinating as its craftsmanship. Discovered in pieces, the lid found in Uttoxeter, Staffordshire, and the base in Cheshire, it was reunited in the 20th century thanks to the tireless efforts of Dr. Philip Nelson, a passionate collector and scholar. Now housed at the Cleveland Museum of Art, it offers a unique insight into Anglo-Saxon religious practices and the artistic skill of a time when faith and art were inseparable.

Historical Context: The Uttoxeter Casket in Anglo-Saxon England

The Uttoxeter Casket is more than just a beautiful relic of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship, it’s a tangible link to a transformative period in English history. Carved around 1050, during the late Anglo-Saxon era, the casket emerged at a time when religious devotion and artistic expression were deeply intertwined.

This was the Romanesque period, a time when religious art and architecture flourished across England. Churches and monasteries were not just places of worship, they were centres of learning, creativity, and community life. The Uttoxeter Casket, with its intricate carvings and symbolic imagery, offers a fascinating glimpse into this world, where faith was at the very heart of society.

A Time of Artistic and Religious Flourishing

In 11th-century England, Christian beliefs shaped every aspect of life. Monasteries weren’t just places for prayer; they were cultural hubs where art, literature, and craftsmanship thrived. From illuminated manuscripts to stone carvings and metalwork, Anglo-Saxon artisans infused their creations with Christian symbolism, turning everyday objects into expressions of faith.

Relics or physical objects linked to saints or key events from the life of Christ were considered powerful connections to the divine. These sacred items were housed in intricately crafted artefacts, like the Uttoxeter Casket, which served both a protective and symbolic purpose.

The casket’s size and detailed carvings suggest it was created to house a relic, possibly a fragment of the True Cross. Placed on an altar, it would have inspired devotion, reminding worshippers of the central stories of their faith and bringing them closer to the divine.

A Possible Connection to Croxden Abbey

Dr Philip Nelson thought that it was most likely made in Lichfield, judging by how close it was found in Uttoxeter. At the turn of the 9th century, Lichfield was located in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, whose heartlands flanked the River Trent. Chad, the first known bishop of Lichfield, was appointed by King Wulfhere of Mercia 675.

There’s a possibility that the Uttoxeter Casket has links to Croxden Abbey, a Cistercian Abbey founded in 1176 by Bertram de Verdun of Alton Castle. While the casket predates the abbey by over a century, it it likely it may have found a later home there.

Monasteries like Croxden were guardians of religious treasures, and the casket would have been a prized item. However, the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII in 1538 brought this era to a brutal end. Abbeys were dismantled, treasures looted or hidden, and centuries of religious heritage were lost.

Discovery and Rediscovery: The Journey of the Uttoxeter Casket

The fragmented journey of the Uttoxeter Casket is as captivating as the artefact itself, mirroring the turbulence of English history. Discovered in pieces, the lid in Uttoxeter, Staffordshire, and the base in Cheshire, the casket’s story spans centuries of upheaval, concealment, and rediscovery. Thanks to the efforts of scholars, collectors, and museums, this remarkable piece of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship has been preserved and appreciated by generations.

The two main sections of the casket were reunited in the 20th century through the dedication of Dr. Philip Nelson, an antiquarian and scholar. From its origins in Anglo-Saxon England to its eventual home at the Cleveland Museum of Art, the casket’s journey is a testament to the enduring value placed on cultural heritage.

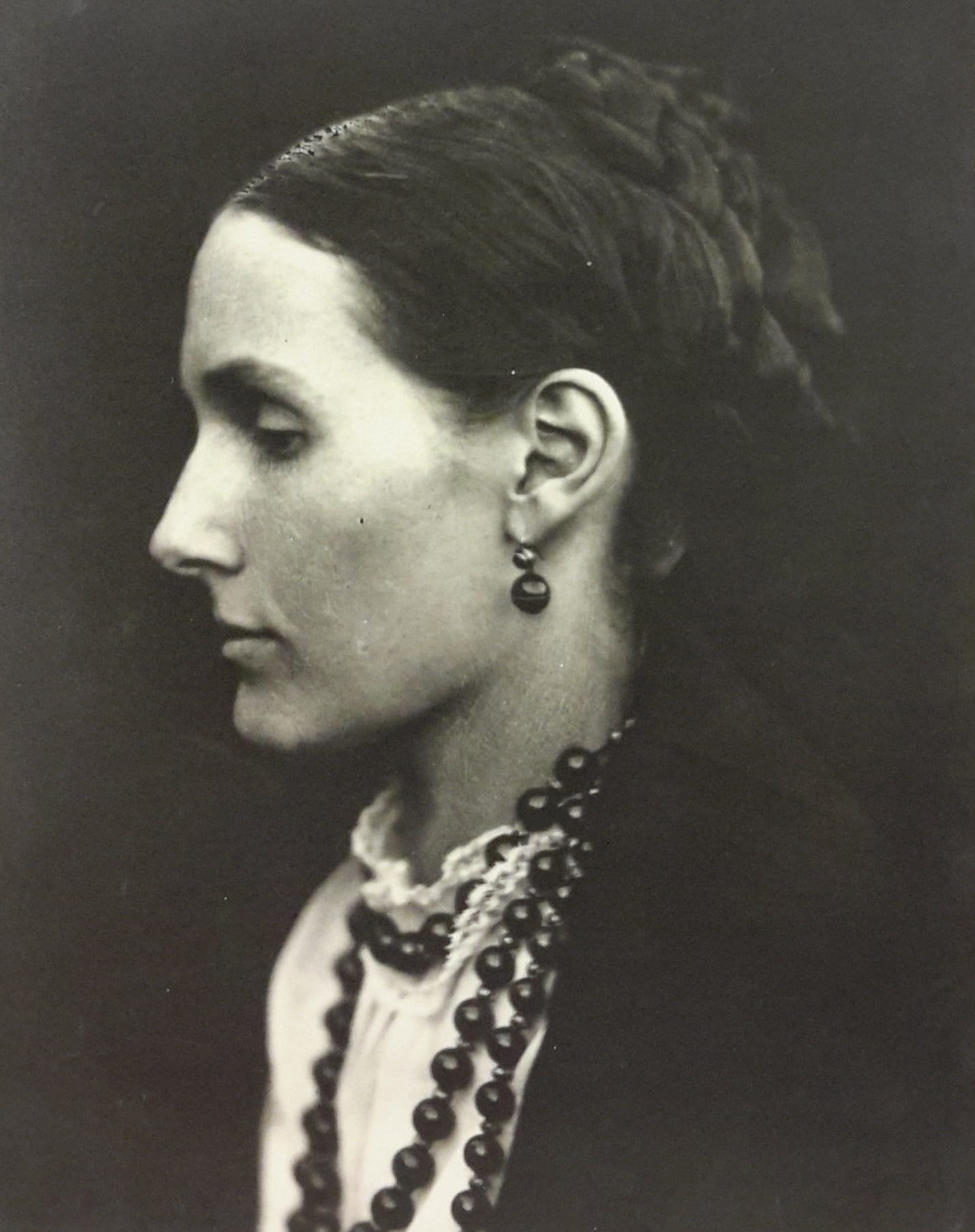

Mary Howitt's home, Balance Street, Uttoxeter, where the lid to the Uttoxeter Casket was found

Discovery of the Lid

The earliest record of the casket’s lid dates back to the late 18th century when it was reportedly found by Ann Botham in a cottage on Balance Street, Uttoxeter. The house, which still stands today, has a plaque commemorating Mary Howitt, the renowned poet who later inherited the casket.

Ann Botham, who lived in the house, is believed to have discovered the lid, possibly passed down through local generations after being hidden during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Croxden Abbey, a Cistercian monastery near Uttoxeter, is a likely origin. After the abbey's dissolution in 1538, many religious artefacts were destroyed or hidden to protect them from Henry VIII’s agents.

The lid remained with Ann Botham’s family, eventually passing to her granddaughter, Mary Howitt (1799–1888), a famous poet and writer best known for The Spider and the Fly and her translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales. Deeply connected to Uttoxeter, Mary took great pride in the family’s history and heritage.

Mary’s daughter, Margaret Howitt (1839–1921), inherited the casket lid and took care to document its provenance. A handwritten note, attached to the inside of the lid, reads:

“This top of an ancient casket was found in a cottage in Uttoxeter, in the early part of this [19th] century, by my grandmother, Ann Botham.”(Signed) Margaret Howitt

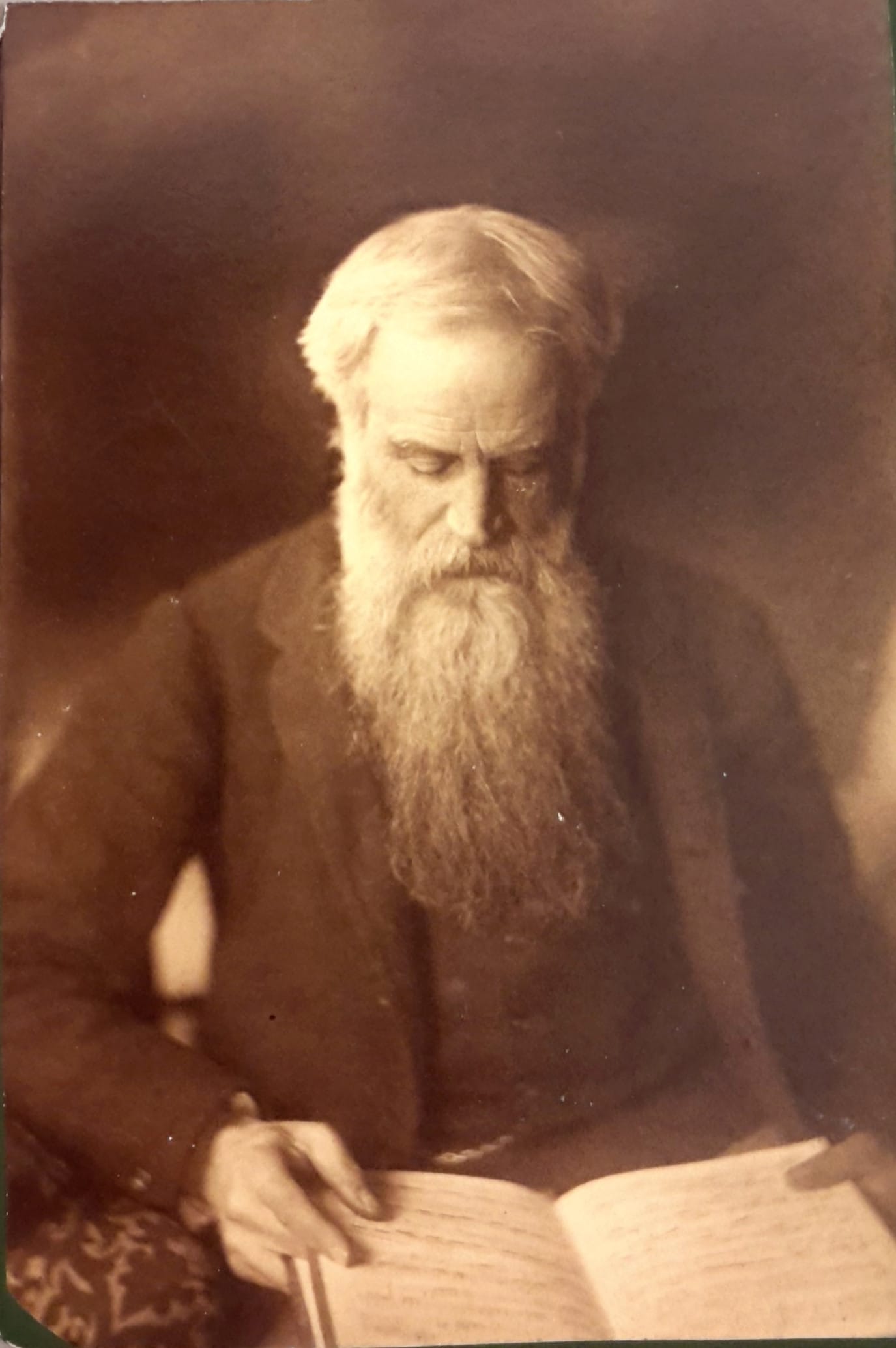

John Hungerford Pollen and the Convent of the Sacred Heart

At some point, the lid left the Howitt family and was acquired by John Hungerford Pollen (1820–1902), a prominent scholar and art historian with a deep interest in medieval antiquities. Pollen spent time in Rome, where Mary Howitt and her husband William had lived for several years before their deaths, suggesting that the casket lid may have passed to him during this period.

After Pollen’s death, his widow, Maria Margaret La Primaudaye Pollen (10 April 1838 – c. 1919), donated the casket lid to the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Hammersmith, London. Given its religious nature, it was likely regarded as a sacred relic by the convent.

In 1936, the convent took the lid to the Victoria & Albert Museum for expert evaluation. It was here that the casket’s significance as a rare Anglo-Saxon artefact was formally recognised, drawing attention from collectors and scholars.

Philip Nelson and the Reunification of the Casket

The base of the Uttoxeter Casket surfaced much later. In 1921, Dr. Philip Nelson, a wealthy antiquarian and scholar of medieval art, purchased the base from a private owner in Cheshire for £175, a considerable sum at the time.

At first, Nelson didn’t realise the base was part of a larger object. However, after learning about the lid held by the Convent of the Sacred Heart, he began to piece the story together. He recognised that the two parts belonged to the same casket and approached the convent to purchase the lid. In 1936, he successfully acquired it for £120, finally reuniting the two halves after centuries of separation.

Following the reunification, Nelson wrote a detailed article titled “An Ancient Box-Wood Casket”, published in the journal Archaeologia in 1937. He meticulously described the casket’s carvings, construction, and historical importance, helping to bring the artefact to wider public attention.

Nelson also loaned the casket to the Victoria & Albert Museum, where it remained on display from 1937 until he died in 1953.

From England to America

After Dr. Nelson’s death, the casket was sold to an American dealer and eventually acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio, where it became part of their renowned medieval art collection.

The Cleveland Museum has ensured the long-term preservation of the casket, featuring it in major exhibitions that highlight its significance as a medieval reliquary. Notably, it was part of the “Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe” exhibition held from 2010 to 2011, which showcased the role of reliquaries in Christian worship.

The casket also made a notable return to England when it was displayed at the British Museum as part of the The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art 966-1066 (November 7, 1984-March 10, 1985) exhibition in London. This allowed the artefact to be appreciated by a British audience once more, reconnecting it with its historical roots.

Challenges of Preservation: An Enduring Legacy

The survival of the Uttoxeter Casket is nothing short of extraordinary. Crafted from a single piece of boxwood, the casket’s intricate carvings have endured centuries of upheaval and environmental change. Unlike stone or metal artefacts, wooden objects are far more vulnerable to decay, making the preservation of this piece a rare achievement.

Time has left its mark. The casket is missing its original lock and one hinge, while the remaining copper alloy hinge shows signs of wear. The lid, slightly darker in tone than the base, may have been hidden in a chimney or another sheltered space, which likely helped protect it from the elements during centuries of concealment.

Despite its imperfections, the casket’s craftsmanship remains awe-inspiring. The skill of its unknown maker, who carved scenes from the life of Christ with astonishing precision, still resonates, reminding us of the artistic and spiritual devotion that defined Anglo-Saxon England.

Detailed Description of the Uttoxeter Casket

The Uttoxeter Casket is a stunning example of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship, a masterpiece that blends religious devotion with artistic excellence. Carved from a single piece of boxwood around 1050, it captures key moments from the life of Christ in intricate detail. This small reliquary offers a rare insight into the spiritual and artistic priorities of medieval England, standing as one of the most significant surviving wooden artefacts of its time.

With its narrative carvings and careful craftsmanship, the casket tells a story that is both deeply personal and profoundly universal, reflecting the faith and artistry of its unknown creator.

Materials and Dimensions

Crafted from boxwood, a material prized for its fine grain and durability, the Uttoxeter Casket is a testament to the skill of its maker. Boxwood’s smooth texture allows for precise, detailed carving, making it an ideal choice for an object of such importance.

The casket is small but significant, measuring 15.7 cm in length, 7.8 cm in width, and 9 cm in height. Its size suggests that it was designed for portability, likely displayed on an altar or carried in religious processions.

Artistic Style and Techniques

The carvings on the Uttoxeter Casket reflect the Romanesque style, which was prevalent during the period. This style is characterised by bold lines, clear compositions, and an emphasis on storytelling.

The figures are depicted with elongated forms and expressive gestures, a hallmark of Anglo-Saxon art. These shared stylistic elements suggest that artists of the time worked within a common visual language, blending influences from both local traditions and wider European trends.

The casket’s creator employed a range of carving techniques to achieve depth and detail. Incised lines outline the figures, while low-relief carving adds dimension. The surfaces are carefully smoothed, creating a contrast that enhances the clarity of the narrative.

Each scene is framed to guide the viewer’s eye, ensuring that the story unfolds in a logical and harmonious sequence. The attention to detail is remarkable, from the folds of clothing to the expressive faces of the mourners and the delicately carved feathers of the angels.

These intricate details reflect not only the skill of the artist but also the importance of the object’s religious function. The casket was designed to inspire contemplation and devotion, making it much more than a mere container, it was a spiritual and artistic treasure, intended to connect worshippers with the divine.

Theological Significance and Narrative Carvings

The carved scenes on the Uttoxeter Casket are more than decorative, they are a carefully chosen sequence of moments that encapsulate the core beliefs of Christianity. Each scene carries deep theological meaning, forming a narrative that invites contemplation and reflection on Christ’s life, mission, and divine authority.

These carvings would have guided medieval worshippers through key moments of the story of salvation, reminding them of God’s presence in the world and Christ’s role in their redemption. The artistry of the casket goes beyond craftsmanship; it serves as a spiritual guide for the faithful.

The Nativity: God Among Us

One of the long sides of the casket depicts the Nativity, showing the infant Christ resting in a manger. This tender and intimate scene emphasises the mystery of the Incarnation, God becoming human and entering the world in the humblest of circumstances.

Mary and Joseph are positioned protectively around the Christ child, embodying care and reverence. The simplicity of the manger scene invites worshippers to reflect on God’s closeness to humanity and the profound humility of Christ’s birth. It is a reminder that salvation comes not through power, but through love and sacrifice.

The Crucifixion: Sacrifice and Redemption

Above the Nativity, the Crucifixion is depicted, a central and powerful theme in Christian theology. Christ hangs on the cross, flanked by mourning figures below and angels above, symbolising both the sorrow of His death and its divine purpose.

The mourners’ expressions of grief and sorrow capture the emotional weight of the moment, while the angels remind the viewer of the heavenly significance of Christ’s sacrifice. This scene reflects the dual nature of the Crucifixion, both human tragedy and divine triumph.

The Ascension: Triumph Over Death

On the opposite side, the casket shows the Ascension, a dynamic scene in which Christ is pulled heavenward by the hand of God. This image captures the moment of transition as Christ leaves the earthly realm to take His place at the right hand of the Father.

Above the Ascension is a depiction of Christ in Majesty, seated in divine glory. This powerful image represents the culmination of His earthly mission and His eternal reign as the ruler of heaven and earth.

Together, these scenes reinforce the hope of eternal life for believers, reminding them that Christ’s victory over death offers the promise of salvation for all.

The Baptism and Entry into Jerusalem: Beginning and Fulfilment

The shorter sides of the casket continue the narrative with two additional key moments from Christ’s life.

One side shows Christ’s Baptism in the River Jordan, marking the beginning of His public ministry. This event symbolises His acceptance of His divine mission and serves as a reminder of spiritual renewal and commitment for believers.

The other side depicts Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, a moment of joy and anticipation. Christ is welcomed by the faithful as the Messiah, in a scene filled with celebration and hope.

These two moments act as bookends to Christ’s earthly ministry, His preparation for the work ahead and the culmination of His mission as He approaches His Crucifixion.

A Narrative of Faith and Salvation

The carved scenes on the Uttoxeter Casket are carefully arranged to guide viewers through Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. Each moment was chosen to reflect the core themes of Anglo-Saxon Christianity, the Incarnation, sacrifice, and divine authority of Christ.

Together, they form a visual narrative of salvation, inviting worshippers to meditate on their own faith journey. The presence of Christ in every scene reinforces the central message of hope and redemption, reminding believers that through Christ’s life and teachings, they too can share in the promise of eternal life.

Far from being a simple decorative object, the Uttoxeter Casket is a theological statement in wood, crafted to inspire reflection, devotion, and a deeper connection to their faith.

A Sacred Purpose: The Casket as a Reliquary

The Uttoxeter Casket wasn’t just a beautiful object, it had a deep spiritual function. It likely served as a reliquary, designed to house sacred relics. These could have included a fragment of the True Cross or another item associated with Christ, objects believed to provide a direct connection to the divine.

The casket’s small size and portability suggest it was intended for use in ceremonies, possibly displayed on an altar during significant religious occasions. It may also have been used for private worship by clergy or pilgrims, offering a tangible focus for prayer and reflection.

Comparison to Other Anglo-Saxon Artefacts

The Uttoxeter Casket stands out even when compared to other notable Anglo-Saxon works. One of the most famous is the Franks Casket, carved from whalebone in the early 8th century. While both caskets feature intricate narrative carvings, the Uttoxeter Casket’s use of wood makes it particularly remarkable, given the fragility of the material and the rarity of wooden artefacts surviving from this period.

The casket’s artistic style and storytelling elements share similarities with illuminated manuscripts like the Hereford Gospels and with carved objects such as the Brescia Casket, a late Roman ivory artefact. These works reflect a broader tradition of narrative art that was deeply connected to Christian teachings. However, the Uttoxeter Casket’s small size and portability make it unique among these objects, suggesting a more personal or ceremonial use.

Unlike the larger and more elaborate reliquaries seen in grand cathedrals, the Uttoxeter Casket may have been intended for more intimate veneration, perhaps by clergy, pilgrims, or a smaller religious community. Its carved scenes, carefully chosen to convey core Christian beliefs, make it a symbolic and devotional object, reflecting the theological priorities of its time.

While each of these artefacts offers valuable insight into the artistic and religious practices of early medieval Europe, the Uttoxeter Casket’s combination of craftsmanship, narrative clarity, and religious significance sets it apart as a truly extraordinary example of Anglo-Saxon woodcarving.

The Symbolism of Wood as a Material

The choice of boxwood for the casket may hold symbolic significance. In Christian tradition, wood often represents the cross, the instrument of Christ’s sacrifice. A reliquary made from wood might have been especially appropriate for holding a relic of the True Cross, as some scholars have suggested. The use of a relatively humble material also reflects the Anglo-Saxon aesthetic, which often combines simplicity with profound meaning.

Benedictional of St. Æthelwold

A Reflection of Anglo-Saxon Devotion

The casket’s creation in 1050, just before the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, places it in a period of significant cultural and religious development. Anglo-Saxon England was a deeply Christian society, and its art often reflected a synthesis of religious devotion and local tradition. The Romanesque style of the carvings on the casket, characterized by bold forms and clear narrative elements, demonstrates an emphasis on teaching and storytelling within the context of faith.

This emphasis on narrative aligns with other Anglo-Saxon works, such as illuminated manuscripts like the Hereford Gospels and the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold, which used imagery to convey spiritual truths. The Uttoxeter Casket fits into this tradition, acting as both a sacred object and a teaching tool.

Enduring Significance

Today, the Uttoxeter Casket serves as a powerful symbol of the intersection of art and faith in Anglo-Saxon England. Its carvings continue to inspire and educate, offering modern viewers a glimpse into the spiritual priorities and artistic achievements of a long-lost world. By preserving and studying the casket, we honour not only the craftsmanship of its maker but also the devotion of the community for whom it was created.

The Importance of Preservation and Future Opportunities for the Uttoxeter Casket

The Uttoxeter Casket is an extraordinary artefact, not just because of its artistic and religious significance, but also due to its remarkable survival over nearly a millennium. Wooden objects from the Anglo-Saxon period are exceedingly rare, as wood is highly susceptible to decay. The preservation of the casket is a testament to the dedication of collectors, scholars, and institutions who have worked to ensure its survival and accessibility.

It has survived centuries of neglect, dispersal, and environmental threats, a remarkable feat for an object crafted from boxwood. Unlike stone or metal, wood is vulnerable to humidity, pests, and physical damage, making its long-term preservation particularly challenging. Over the years, the casket has experienced some losses, its lock and one hinge are missing, and the lid shows evidence of having been hidden in a chimney or other protected space, contributing to its darker colour. Despite these imperfections, the casket remains structurally sound, and its carvings are well-preserved, allowing modern viewers to appreciate its artistry.

The Role of Museums in Safeguarding Heritage

Museums play a critical role in the preservation and interpretation of artefacts like the Uttoxeter Casket. By housing the casket in a controlled environment, the Cleveland Museum of Art protects it from environmental damage and ensures its availability for future generations. In addition to physical preservation, museums facilitate scholarly research, enabling historians and art experts to uncover new insights about the casket’s origins, use, and broader historical context.

A Vision for the Casket’s Return to Staffordshire

Given the casket’s deep connection to Staffordshire, there is a compelling case to bring it back, even temporarily, to its place of origin. The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent, known for its outstanding collections and commitment to local history, would be an ideal venue for an exhibition featuring the Uttoxeter Casket.

This is something I’m working on to get the ball rolling, to see if it is possible.

Such an exhibition would not only allow local communities to reconnect with this extraordinary piece of their heritage but also enhance the casket’s story by situating it in the broader context of Anglo-Saxon history in the Midlands. The Potteries Museum has a strong reputation for hosting successful exhibitions, and featuring the casket alongside other artefacts from the region could provide a richer understanding of the area’s historical significance.

The Significance of Reconnecting the Casket with Its Origins

Bringing the Uttoxeter Casket back to Staffordshire would serve several important purposes:

- Cultural Reconnection: The casket’s discovery near Uttoxeter ties it directly to the local community. Displaying it in Staffordshire would strengthen public awareness and pride in the region’s Anglo-Saxon heritage.

- Educational Opportunities: Hosting the casket would allow schools, historians, and the general public to engage with an artefact that vividly illustrates the art and faith of medieval England. Educational programs and talks could delve into its artistic, religious, and historical aspects.

- Increased Accessibility: While the Cleveland Museum of Art has done a remarkable job preserving and studying the casket, bringing it to the Potteries Museum would provide access to audiences in the UK, particularly those with a personal connection to Staffordshire and its history.

- Highlighting the Midlands’ Historical Importance: The Midlands was a vital centre of Anglo-Saxon culture, as evidenced by other significant finds like the Staffordshire Hoard. The casket would complement existing collections and help to tell a more comprehensive story of the region’s past.

Planning for the Exhibition

To bring the Uttoxeter Casket to the Potteries Museum, careful planning would be required. Key steps might include:

- Collaborating with the Cleveland Museum of Art: Building a relationship with the Cleveland Museum and proposing a loan agreement that ensures the artefact’s safety and proper care during transport and display.

- Securing Funding: Applying for grants and sponsorships to cover costs associated with insurance, transportation, and exhibition preparation.

- Creating an Engaging Exhibit: Designing an exhibition that contextualises the casket within Anglo-Saxon history and culture, perhaps including related artefacts, digital reconstructions, and educational materials.

- Community Engagement: Involving local schools, historical societies, and the general public to create a sense of excitement and connection around the exhibition.

A Future Filled with Possibility

The potential to bring the Uttoxeter Casket back to Staffordshire represents an exciting opportunity to celebrate the region’s heritage and share a piece of Anglo-Saxon history with a new audience. Such an initiative would honour the casket’s origins while contributing to its legacy as a bridge between the past and the present.

The Legacy of the Uttoxeter Casket

The Uttoxeter Casket is far more than a beautifully carved wooden box, it is a rare and extraordinary link to the faith, artistry, and history of Anglo-Saxon England. Crafted around 1050, the casket’s journey has taken it from a time of deep religious devotion through centuries of obscurity and rediscovery. Along the way, it has endured as a symbol of resilience and devotion, a reminder of the enduring power of art to transcend time and connect us with the past.

As the casket continues to inspire awe and curiosity, it stands as a testament to the interwoven relationship between faith, craftsmanship, and history. Its intricate carvings and carefully chosen narrative scenes invite us to reflect on the beliefs and values of those who came before us, while also prompting us to consider the importance of preserving such treasures for future generations.

Bringing the Uttoxeter Casket home, even temporarily, could offer a renewed sense of pride and connection to the rich heritage it represents. It would serve as a tangible link to Staffordshire’s history, fostering a deeper appreciation for the region’s contribution to medieval art and culture.

This casket is more than a relic of the past, it is a living piece of history. It reminds us that, despite the passage of centuries, art and faith remain powerful forces, capable of bridging the divide between past and present, belief and identity.

In the story of the Uttoxeter Casket, we see a timeless truth: the power of stories, symbols, and craftsmanship to inspire, endure, and connect us across the ages.

Love local history? Support my work and uncover Stoke-on-Trent's stories here;

Thank you.