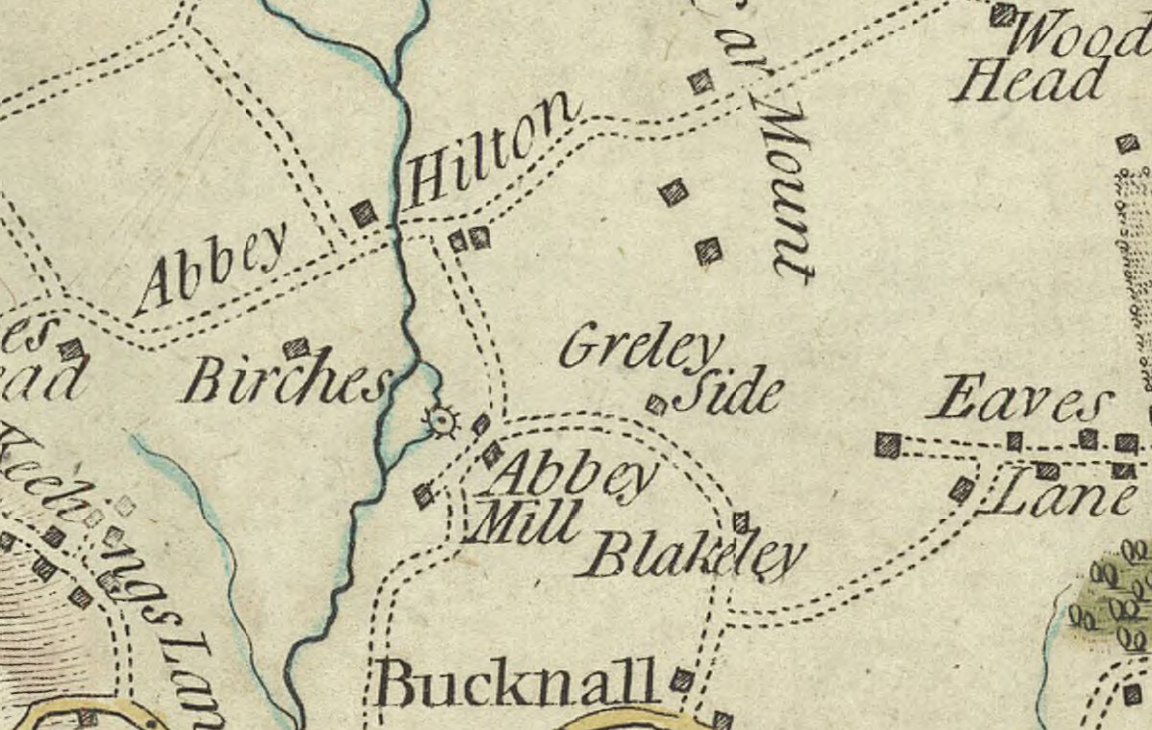

Hulton Abbey, a former Cistercian monastery, is a relic of medieval England and the country's rich monastic history. Established between 1219 and 1223 by Henry de Audley, it is located in Abbey Hulton, a suburb of Stoke-on-Trent. It encapsulates over seven centuries of religious devotion, economic challenges, and social transformations. This area was originally known as 'Heltone' in the Domesday Book, which signifies 'hill town'. The abbey reflected the typical Cistercian preference for remote, tranquil sites conducive to their ideals of self-sufficiency and spiritual contemplation. It is also shown on some maps as Abbey Hilton, or Hilton Abbey.

Watch my video about Hulton Abbey on YouTube

As a daughter house to the Cistercian Combermere Abbey in Cheshire, Hulton Abbey was the last of three such monasteries founded in Staffordshire, the others being Croxden Abbey and Dieulacres Abbey. Despite its noble beginnings and the continuous patronage from the Audley family and other local landowners, Hulton Abbey struggled financially. It was among the poorest in England, with its monastic income consistently lower than that of its peers, rarely exceeding the modest sums that marked its economic struggles through the ages.

Origins and Foundation

The foundation of Hulton Abbey in 1223 by Henry de Audley marks a significant chapter in the expansive history of monasticism in England, where over 700 monastic communities were established from the late 6th century until the dissolution under Henry VIII. This era, characterized by intense religious fervour, saw the Cistercians emerge as a major monastic order, renowned for their strict adherence to austerity and self-sufficiency.

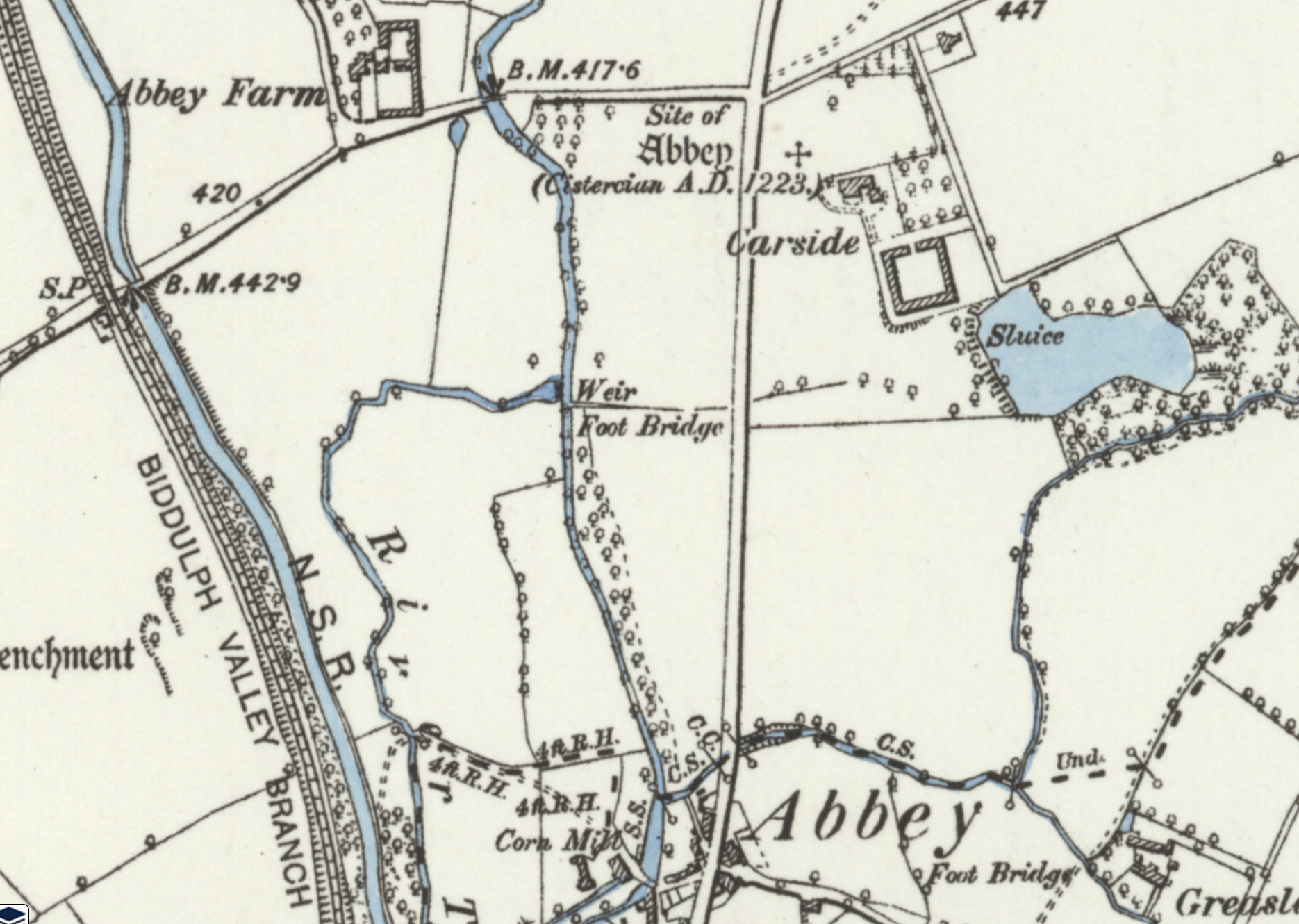

Chosen for its remote location in the secluded Trent Valley, the site of Hulton Abbey portrayed the Cistercian ideal of isolation which was believed to enhance spiritual focus and communal self-reliance. This setting was not only strategic but also symbolic, representing a withdrawal from worldly affairs to achieve greater spiritual purity. The abbey was strategically placed on the eastern side of the upper Trent Valley.

The foundation of Hulton Abbey was also deeply rooted in the social and spiritual aspirations of its patron. Henry de Audley, a local nobleman, established the abbey to ensure the spiritual welfare of his family—an act reflecting a common motive among the nobility of the time. This practice of founding religious houses was often seen as a way for noble families to secure divine favour and eternal salvation for themselves and their descendants. Indeed, the abbey was intended to serve as a spiritual haven where prayers for the Audley family's souls would be perpetually offered.

The initial endowment by Henry de Audley included not only land inherited from his mother but also additional tracts that were purposefully acquired to form a sufficient estate to support the abbey. This foundation was followed by further grants from local landowners such as Simon de Verney and Henry de Verdon, who contributed lands in Normacot and Bucknall respectively, enriching the abbey’s holdings and ensuring its economic viability, at least in its early years.

These endowments included not only substantial tracts of land but also the earnings of several churches, which provided the abbey with vital sources of revenue. The rights to these churches allowed the abbey to collect tithes and other ecclesiastical dues, which were essential for its financial survival.

However, the economic reality of the abbey was one of constant struggle. The patronage it received, while generous, was not sufficient to secure its financial prosperity. The abbey's income was significantly lower compared to other religious houses in the region. For instance, records from 1291 show the abbey’s annual income was over £26, but by 1354, after the devastation of the Black Death, this had plummeted to just £14. This was indicative of the wider economic hardships faced during the era, which severely impacted the abbey's financial stability.

Economic Diversity

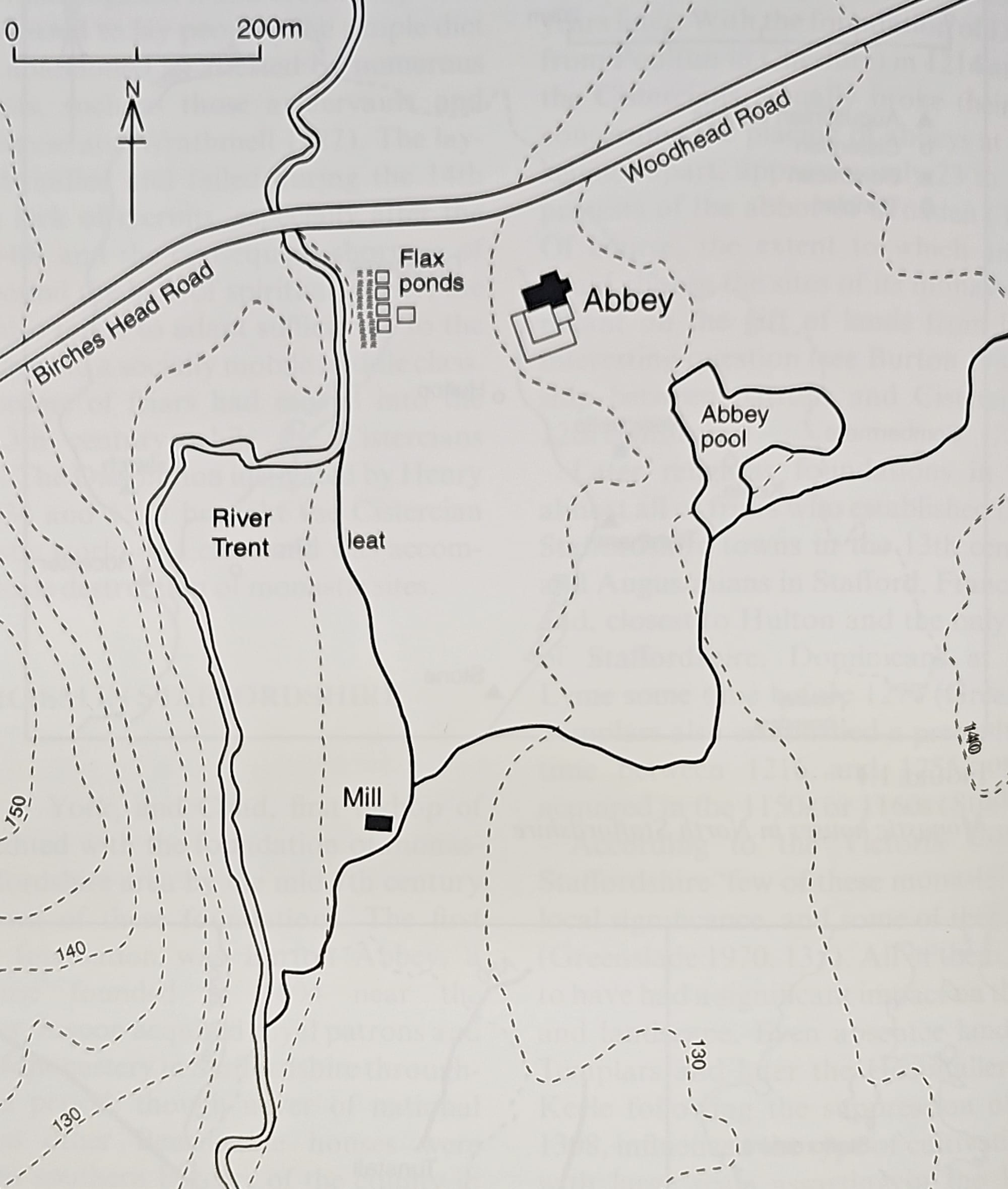

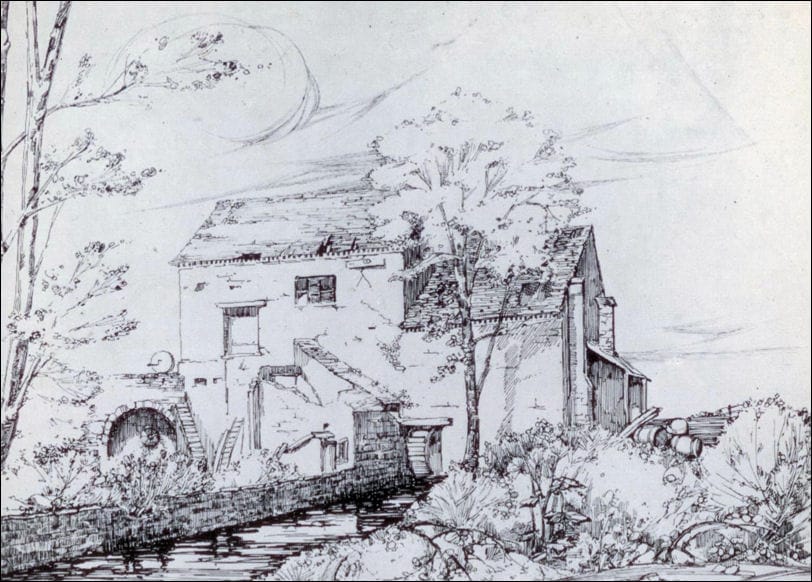

To cope with these financial challenges, the monks of Hulton Abbey engaged in various money-making activities. Initially, they focused on sheep farming, which was a common economic backbone for many monastic communities due to the wool trade's profitability. The abbey also operated a fulling mill on the River Trent and a tannery, further diversifying its income sources to include agricultural processing and leather production, which were essential for local economies.

Fulling, also known as tucking or walking, is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven cloth to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and to make it shrink by friction and pressure. The work delivers a smooth, tightly finished fabric that is insulating and water-repellent.

By the 16th century, in response to continuing economic pressures, the abbey further diversified its operations into coal mining and smithing. These ventures were part of a broader trend among monastic institutions to explore new opportunities. The abbey's engagement in coal mining was particularly noteworthy, reflecting the region's growing importance as a mining centre. This not only provided the abbey with additional revenue but also integrated it more deeply into the industrial fabric of the area.

Early Ceramics and Pottery Creation

The monks of Hulton Abbey were also involved in the production of pottery and encaustic tiles, particularly during the Middle Ages. This activity was part of their broader economic efforts to support the abbey. Encaustic tiles, which are ceramic tiles inlaid with patterns made from different colours of clay, were among the products made by the monks. These tiles were often used to create decorative floorings in churches and other significant buildings, reflecting a common practice among monasteries of the period which often engaged in crafting religious and ornamental objects. Many of these tiles were found during excavation and it is thought that this is one of the earliest examples of ceramics made in North Staffordshire.

The production of such tiles at Hulton Abbey is particularly notable because it highlights the monks' skills in crafts that were essential both for their self-sufficiency and for generating income. The tiles from Hulton Abbey, like those from many monastic sites, would have been distinctive, featuring designs that might include geometric patterns, floral motifs, and heraldic emblems, which were popular during the medieval period in Europe.

Water Power

About 150 meters southeast of the church, the remnants of a large dam, roughly 80 meters in length and made from earth and stone, are visible. The dam's outer face reaches up to 3.2 meters in height and features a stepped profile at both its northwestern and southeastern ends. It originally held back a significant pond that powered the abbey mill. This pond has since been drained and filled in during recent times. While the dam itself is protected as a scheduled monument, the former site of the pond is not. Water from this pond once flowed westward into the River Trent. South of the monastic core buildings, this locale likely served as a centre for industrial activities, essential to the monastery’s economic foundation, as suggested by historical records. Archaeological digs have revealed well-preserved medieval water channels here, and this area is also under protection.

West of the monastic core, near the River Trent in the valley's bottom, were fishponds owned by the abbey. These have now been replaced by residential developments along a road aptly names Fishpond Way and are not part of the protected site.

Architectural Evolution

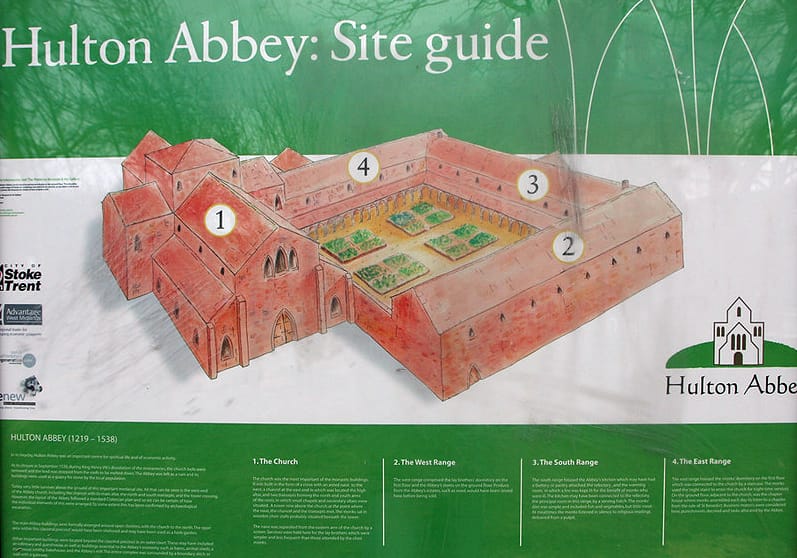

Hulton Abbey's architecture, while adhering to the characteristic Cistercian layout, adapted over the centuries, mirroring broader trends in Gothic architecture and the specific needs of its community. Initially constructed with a cruciform church positioned at the north, the abbey was designed around a central cloister, which served as the heart of monastic life. This layout not only facilitated the monastic routine of prayer and labour but also reflected the Cistercian ethos of simplicity and functional elegance.

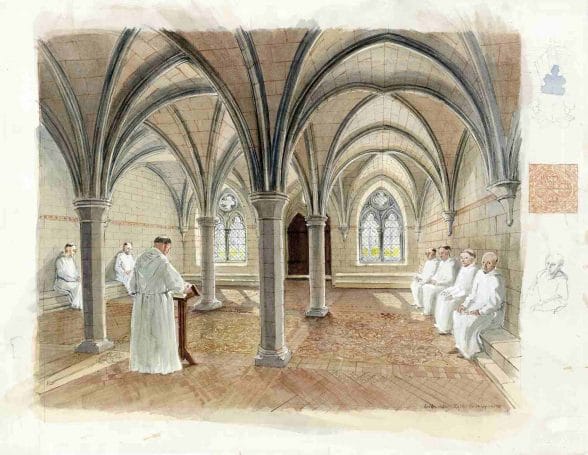

The core architectural elements of Hulton Abbey included a chapter house, dormitories, a refectory, and various ancillary structures. The chapter house, typically a venue for daily monastic meetings and a repository for the abbey's records, was constructed in 1270, showcasing the early adoption of Gothic architectural elements. This building was integral to the governance of the abbey, reflecting its role as a centre of religious and administrative activity.

The abbey church, the most prominent feature of the abbey, was built to a standard cruciform design. This included a relatively short nave and a transept with two adjoining chapels at each end, a typical feature in Cistercian abbeys aimed at accommodating the liturgical practices and communal gatherings of the monks. The church measured 42.5 meters in length and 32 meters in width, which underscored the abbey's modest scale compared to larger Cistercian establishments.

Architectural modifications over the years were particularly evident in the evolution of the abbey's windows. Initially, the abbey featured simple lancet windows, which are narrow and pointed arch windows typical of early Gothic architecture. These provided sufficient light while maintaining the austerity favoured by the Cistercian order. However, as architectural styles evolved during the Gothic period, the abbey's windows were gradually replaced with more complex bar tracery designs. This transition not only allowed more light to enter the sacred spaces but also enhanced the aesthetic appeal of the buildings, aligning them with the ornate styles becoming prevalent in the architecture of the time.

The chapter house and church at Hulton Abbey featured some of the earliest examples of bar tracery windows in the British Isles.

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The arrival of the Black Death in the mid-14th century exacerbated the abbey’s precarious situation. This devastating plague led to significant loss of life, including among the monastic community at Hulton Abbey, which reduced the number of active members involved in productive and administrative tasks. Furthermore, the widespread mortality reduced the labour force available, impacting agricultural output and, consequently, the abbey’s revenues from land holdings.

In addition to the direct impacts of the Black Death, subsequent outbreaks of plague in the following decades continued to diminish the abbey's population and economic strength. Each wave of disease not only decreased manpower but also disrupted social and economic structures, leading to reduced agricultural productivity and less income from tenant farmers.

By the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, initiated by Henry VIII in the 1530s, Hulton Abbey was in a financially vulnerable state. The abbey’s income had dwindled to a point where it could no longer sustain its operations independently. The Dissolution itself was a political and religious manoeuvre intended to consolidate the wealth and property of the monasteries under the crown, but for Hulton Abbey, it also marked the end of its struggle for economic survival. The abbey, unable to generate sufficient income to justify its exemption, was among the many religious houses that were dissolved and appropriated by the state. The king granted the monks pensions, with the last abbot, Edward Wilkyns, receiving a sum of £20 a year.

The abbey's assets, primarily its land and physical structures, were seized and sold off, leading to the dispersal of its territories. The bells were sold the roof tiles removed and the lead roof melted down. There was melted lead waste found during one of the excavations, which meant that they melted the lead down on the site in a circular lead-melting hearth that was also found, using wood from the roof for the fire.

In the years following the dissolution, the physical remnants of Hulton Abbey fell into disrepair and served local needs. Stone and other materials from the abbey’s structures were repurposed as quarry materials, and used in local construction projects such as Abbey Farm, which was in existence by the early 18th century when it was the home of John Bourne, grandfather of the Primitive Methodist leader Hugh Bourne.

After the Dissolution

The crown quickly moved to dispose of its assets, and in 1539, the abbey’s site, its lands in Hulton and Stoke, and a coal mine were leased to Stephen Bagot of London, who had purchased the abbey's movables during the dissolution.

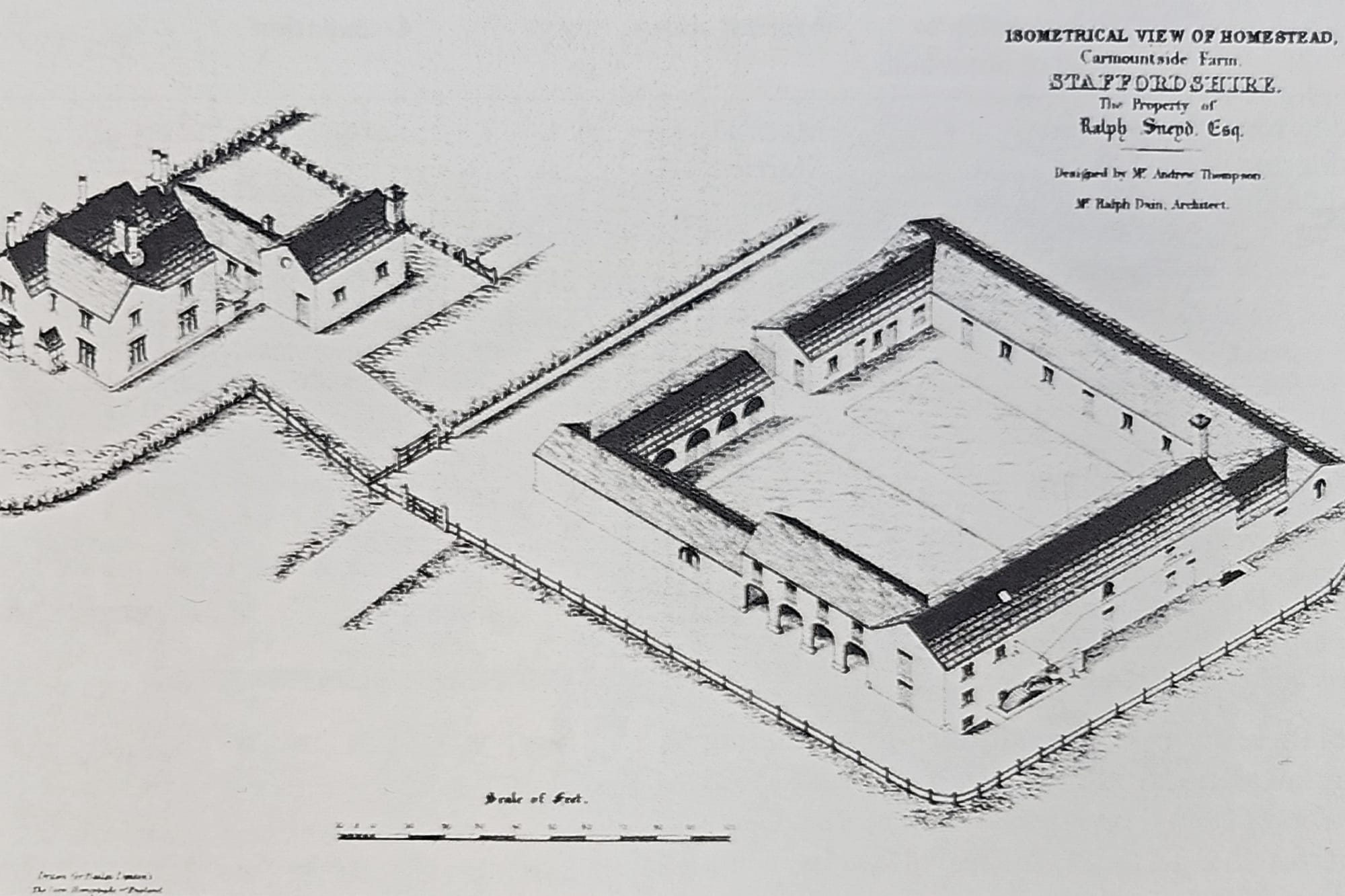

By 1543, the Crown formally granted the manor of Hulton, the site of the abbey and all its other possessions in Hulton, Sneyd, Baddeley, Milton, and Burslem to Sir Edward Aston of Tixall. He later sold it in 1611 to William Sneyd of Keele, marking the beginning of a long tenure by the Sneyd family over these lands. This transition from monastic to private hands signalled a new chapter in the usage and administration of the former abbey lands.

Throughout the 17th century, the Sneyds maintained control, with Ralph Sneyd reported to own approximately 1,100 of the 1,400 acres in Abbey Hulton by 1838. This period also saw the utilization of the land for various industrial activities known to be associated with the monastic community before the dissolution; these included the tannery in operation by the end of the 13th century, the fulling mill on the River Trent, and early pottery-making efforts which included the production of encaustic tiles.

The Adams family, who are the oldest potting family whose records exist, worked the pot works of the abbey for many generations after the dissolution and by the mid-17th century, the Adams family, were still active in the area, with Thomas Adams of Birches Head exploiting a coal mine on his estate at Abbey Hulton. This mining tradition continued under different ownership, evolving into a significant economic activity with the Abbey Hulton Colliery still operational by 1800.

By 1951, the Sneyd family decided to sell the remaining portions of their agricultural holdings, which included the 150-acre Abbey Farm, the 26-acre Mill Farm, and the 78-acre Birches Head Farm. These properties were part of the broader dispersal of the Keele estate that year. Originally part of the ecclesiastical lands associated with Hulton Abbey, these farms had long since been repurposed for agricultural use, reflecting a significant transformation in both their function and economic contribution to the region.

Carmountside Farm and the Rediscovery of the Abbey

At some point after the abbey was dissolved a farm was built on the site and in 1611, Carmountside Farm was under the stewardship of Beatrice Smith, a widow, and likely her son Roger Smith. A lease was granted to Roger's son, Thomas, by the Sneyds in 1650. Thomas paid taxes on two hearths in Hulton in 1666 and paid £4 18s for the Hulton Abbey rental in 1680. He passed away in 1693, with his estate valued at £27 0s 8d.

Subsequently, the farm transitioned to the Heath family. John Heath was recorded as the occupant in 1698. His son, also named John, died in 1738, the same year as his widow, Sarah. William and Hannah Heath maintained the farm until at least 1748. By 1758, Robert Clarke was the tenant, followed by Samuel Worthington from 1781 until he died in 1812 at the age of 79. John Worthington and his family then inhabited the farm from 1813 to 1831.

By then, no traces of the abbey ruins were visible above ground. Historian John Ward noted in 1843 that although no structures remained, the original site of the Abbey was identifiable by the uneven ground, a testament to where the foundations once lay. He mentioned that the materials had been used about a century prior for constructing the nearby Bucknall Church.

In 1854, the farm site was disturbed during the construction of a new farmhouse and outbuildings commissioned by Ralph Sneyd Esq. Workers unearthed remains of monks, still clad in leather shoes or boots, with hazel rods used in place of coffins, during cellar excavations.

This new farm, completed in 1855 to the west of the original farmhouse, was initially leased to William Blackshaw in 1861 and later to the Chadderton family by 1881.

The rediscovery of Hulton Abbey in the 19th century initiated a new chapter in its history, focusing on archaeological investigation and heritage conservation. This period marked the transition from obscurity back into historical significance, as archaeologists began to explore and uncover the physical remnants of the abbey's past.

In 1884, during drainage work at Carmountside Farm by workmen employed by the owner Reverend Walter Sneyd, the ruins of the abbey were again uncovered. This led the Reverend and Charles Lynam to have more thorough excavations that mapped out the main structures. These included the church, chapter house, dormitories, kitchen, and refectory, all organized around a square cloister with the church positioned to the north, known collectively as claustral buildings.

Decorative coffin lids, medieval floor tiles, and pottery shards were found, along with human remains in the church area. These finds were removed and taken to Keele Hall and some of the fragments of the abbey were made into a garden folly which was unfortunately demolished in 1950.

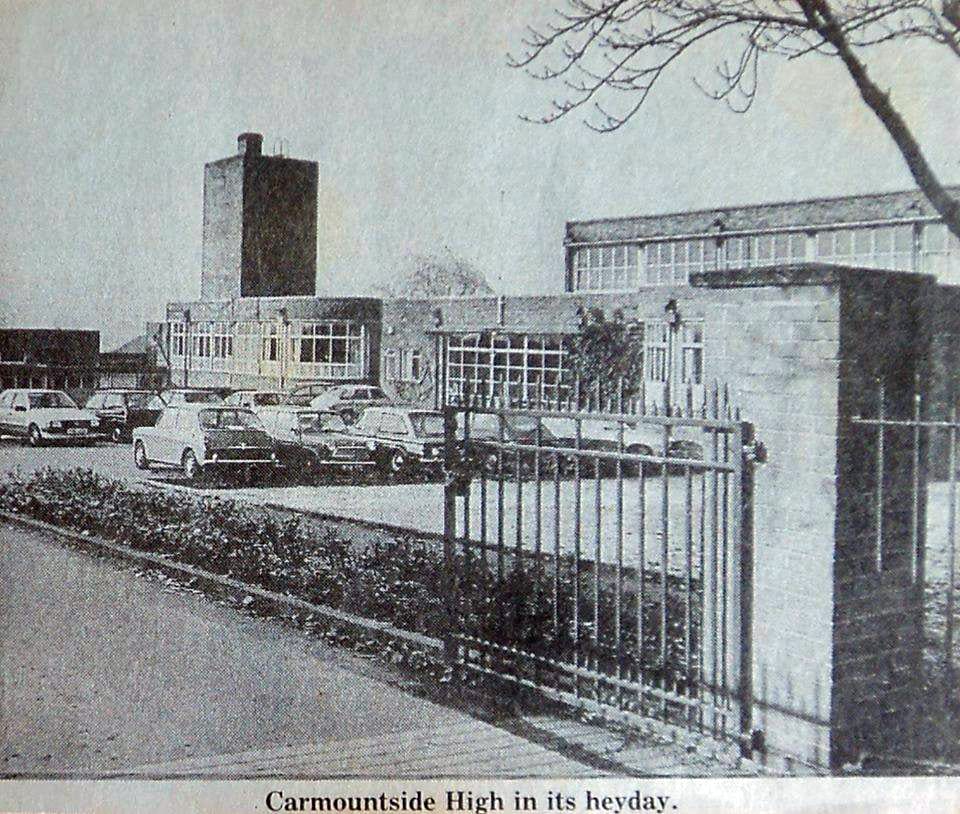

From 1889 to around 1900 the farm was occupied by the Goodwin family. It was this family that was working the farm when the council acquired the land to build the current housing estate of Abbey Hulton, which was completed in 1936. This led to more archaeological digs and there was talk of the farmhouse becoming a museum for the site. Because of the large population of the area, a school was built and Carmountside Farm was demolished and replaced with Carmountside High School in 1938.

From 1930 to 1983 more focused digs further explored the church and its surrounding buildings. The school was demolished in 1987 and this gave space for major excavations between 1987 and 1994 which expanded on the earlier discoveries, providing greater insights into the layout and monastic life of the abbey.

Burials

Moreover, numerous burials found on-site have provided profound insights into the demographics, health, and mortuary practices of the monastic community and its associates. These burials allow researchers to study aspects of medieval life such as diet, disease, and social structure, enriching our understanding of the population that once inhabited the abbey.

The primary burial site was located to the northeast of the church. During archaeological investigations from 1987 to 1994, the remains of 91 individuals were unearthed, predominantly men, although women and children were also found among the deceased. Various artefacts accompanied these burials, such as a pilgrim's staff and a wax chalice, enhancing the historical context of these interments. Particularly notable was a wax seal bearing the impression of the church of Santo Spirito in Sassia, Rome, discovered with one of the remains. Professor John Cherry suggested that this seal was likely affixed to a document granting an indulgence, typically obtained during a pilgrimage.

Within the church, the resting places of the Audley family, as well as those of other local aristocrats and prominent clergy members, were established. Initially, these burial spots were exclusively for the Audleys. By 1322, the church had expanded burial rights to any benefactor who supported its construction, illustrating a widening of community engagement and the growing importance of such donations. Sir James de Audley, renowned for his valiant service under the Black Prince at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, was laid to rest with his wife in the abbey church's choir, near the high altar.

Hugh Despenser the Younger

In the 1970s, archaeologists at Hulton Abbey unearthed the fragmented remains of a male, decapitated and disarticulated, missing several vertebrae and a thighbone. The placement of these remains in the chancel indicated they likely belonged to a person of significant status, possibly a wealthy member of the congregation or a member of the benefactor’s family. Subsequent analyses conducted in 2004 at the University of Reading suggested that the individual had been subjected to hanging, drawing, and quartering, with radiocarbon dating placing the remains between 1050 and 1385. Additional testing indicated the man was over 34 years old at the time of his death.

In 2008, Dr Mary Lewis of the University of Reading identified these remains as those of Hugh Despenser the Younger, based on various factors including his known familial connections through marriage to the Audley family. Hugh Despenser, son of Hugh Despenser the Elder, Earl of Winchester, was a prominent figure at the court of Edward II, reputedly also his lover. His significant influence and political manoeuvres made him many enemies, including Queen Isabella, the king’s estranged wife. In 1326, Isabella and Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, overthrew Edward II and condemned Despenser to death for treason. Following Isabella’s orders, Despenser suffered a gruesome execution; he was hung, drawn, and quartered, a fate detailed vividly in contemporary and later accounts, including one by Froissart that graphically described his castration and disembowelment before his heart was removed and burnt.

Following his execution, Despenser's body was mutilated further; his head was displayed above London’s gates, while his torso was quartered and displayed across various cities. In 1330, his widow Eleanor de Clare was permitted to collect his remains, though she only retrieved his head, a thigh bone, and some vertebrae.

The remains found at Hulton Abbey, missing significant parts and bearing signs of violent death, aligned with historical records of Despenser’s execution and the subsequent handling of his body and were missing the bones that his widow collected.

This connection is underscored by the abbey’s location on lands owned by Hugh de Audley, Despenser’s brother-in-law, enhancing the plausibility that these were indeed the remains of Hugh Despenser the Younger. The age of the remains supported Dr. Lewis's identification, the historical context of their interment, and the nature of the injuries they exhibited, consistent with the documented brutality of Despenser’s death.

Hulton Abbey Today

The passage of the Housing Act of 1919 marked a pivotal turning point for the area surrounding Hulton Abbey. This legislation addressed the severe housing shortages following World War I by providing government support for local authorities to build new housing. As a result, Stoke-on-Trent, like many other British cities, experienced substantial suburban expansion during the post-war period. The land that once belonged to Hulton Abbey was gradually incorporated into the growing urban fabric, transforming it into a residential suburb.

Today, Hulton Abbey occupies a unique position within this suburban landscape. It has been repurposed into a public open space, serving as a historical landmark and a green refuge amid residential developments. The abbey is recognized as a site of historical importance and is protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979. This protection is vital for preserving its remains for future study and public education. However, despite this status, Hulton Abbey is listed as Heritage at Risk. This designation indicates that the site is in a fragile condition and at risk of further degradation due to environmental and human factors. It underscores the need for ongoing conservation efforts to stabilize and restore the site as much as possible.

For those interested in seeing artefacts recovered from the site, the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in nearby Stoke-on-Trent houses a collection of items excavated from Hulton Abbey. Visitors to the museum can view encaustic tiles, pottery, and other remnants that offer insights into the daily life and artistic endeavours of the abbey's inhabitants. The museum also provides additional historical context about the area and its development, enhancing the visitor's understanding of the regional heritage. This combination of on-site exploration and museum exhibition visits Hulton Abbey and its surrounding areas a complete historical experience.

If you would like to visit Hulton Abbey, you can find it here;

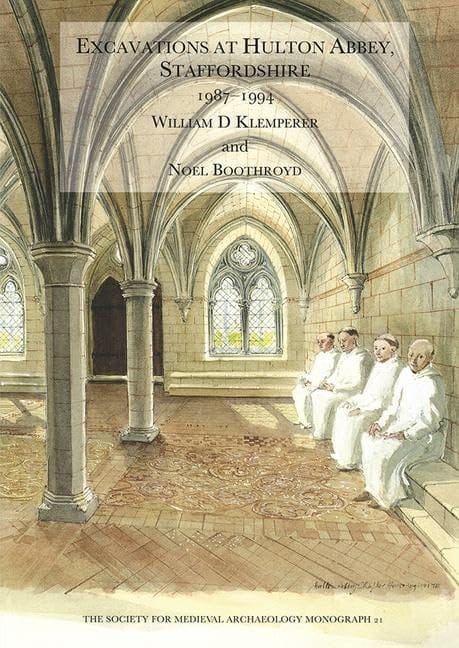

Excavations at Hulton Abbey, Staffordshire

I would also highly recommend reading the book Excavations at Hulton Abbey, Staffordshire by William D Klemperer and Noel Boothroyd if you would like an in-depth look at Hulton Abbey, the excavations throughout the years and the finds.

Please sign my petition to help save buildings like this

Thank you for reading!

If you like what you have read, please feel free to support me by following and signing up for my newsletter and/or buying me a coffee!

If you love our local history, don't forget to follow me, check out more of my videos and my website http://www.theredhairedstokie.co.uk

Don't forget to subscribe to my YouTube channel - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCCA246yaLXVDHSB-MrFMB2A

Check out my recommended reading list