Join me on a captivating journey as we delve into the remarkable life of Molly Leigh, the Burslem Witch. Uncover the true history of this extraordinary woman—a fiercely independent, wealthy landowner who defied societal norms in 18th-century England. We shed light on Molly's life, her alleged witchcraft, and the enduring legacy she left behind. Discover a story of strength, resilience, and the pursuit of personal freedom as we unravel the enigma of Molly Leigh, the trailblazing woman whose legend still echoes through the centuries.

This article is part of this week's podcast which you can listen to here;

Or if you prefer, you can watch it on YouTube here;

Don't forget to subscribe on YouTube so you don't miss an episode or video!

If you grew up in or around Stoke-on-Trent, it is more than likely you have heard the stories of Molly Leigh, the supposed witch of Burslem. Here are the myths and stories that most people have heard.

Born in 1685 in a cottage on the edge of the moors, it is said that a few hours after she was born she could chew a piece of bread crust. It is also said that she refused her mother's milk and fed from animals.

Molly had a facial disfigurement and was allegedly so ugly that she was shunned by the locals, her only friend being a blackbird. She made her living selling milk from her herd of cows, although she was accused of watering down her milk.

The local parson, Reverend Spencer, was not happy that she did not attend church every Sunday and so accused her of witchcraft. He claimed that she made her blackbird sit on the sign of The Turk's Head pub which made the beer sour and gave the patrons rheumatism. She also apparently put a spell on the Reverend Spencer when he tried to shoot her bird which kept him drunk for three weeks.

When Molly died in 1748, the story goes that the funeral was led by the Reverend Spencer, and then drinks were had afterwards in The Turk's Head. When the party went back to her cottage, it seems that Molly was sitting in her nook by the fire knitting.

Spencer, along with some local clerics exhumed her body at 1 am in the morning, threw her live blackbird in the coffin and reburied her, north to south, to appease her ghost.

Her Life

The truth about Molly Leigh's life, however, is somewhat different.

Born Margarett Leigh in 1685, she lived in the family home, Jackfield Farm. Made up of a thatched cottage and farm buildings, it had been in the family for some time. The house was occupied by Richard Leigh in 1640 and the land had probably been in the family since at least the beginning of the century.

It seems that Richard Leigh was her father and her mother was Sarah Leigh, who re-married after what must have been Richard's death. She married Joseph Booth, who became Molly's stepfather and her mother became Sarah Booth. She grew up with her mother and stepfather, although it seems that she did not get on with the latter at all.

Because she was an only child, there is no record of her having any siblings, the farm was left to her and it had substantial land with other holdings nearby. She was undoubtedly an astute and independent businesswoman. Her farm generated income by selling hay and straw, and dairy farming. Molly also generated further income by leasing out her other lands such as Wall Flatt, Burslem, which she leased out to a friend called Alice Beech.

The fact that her face was deformed seems to be true, although there are a few explanations as to why. The most likely scenario is that she contracted smallpox as a child, which left many survivors disfigured, especially on their faces. Children and people are hurtful even today to people that look different, so I imagine it would have been even worse for her back then.

Molly was also not a lonely woman, in her will she left her estate to her mother who outlived her, her cousins, her friends and her aunt and uncle. In fact, by the time Molly died, she was a very wealthy woman and well-known woman.

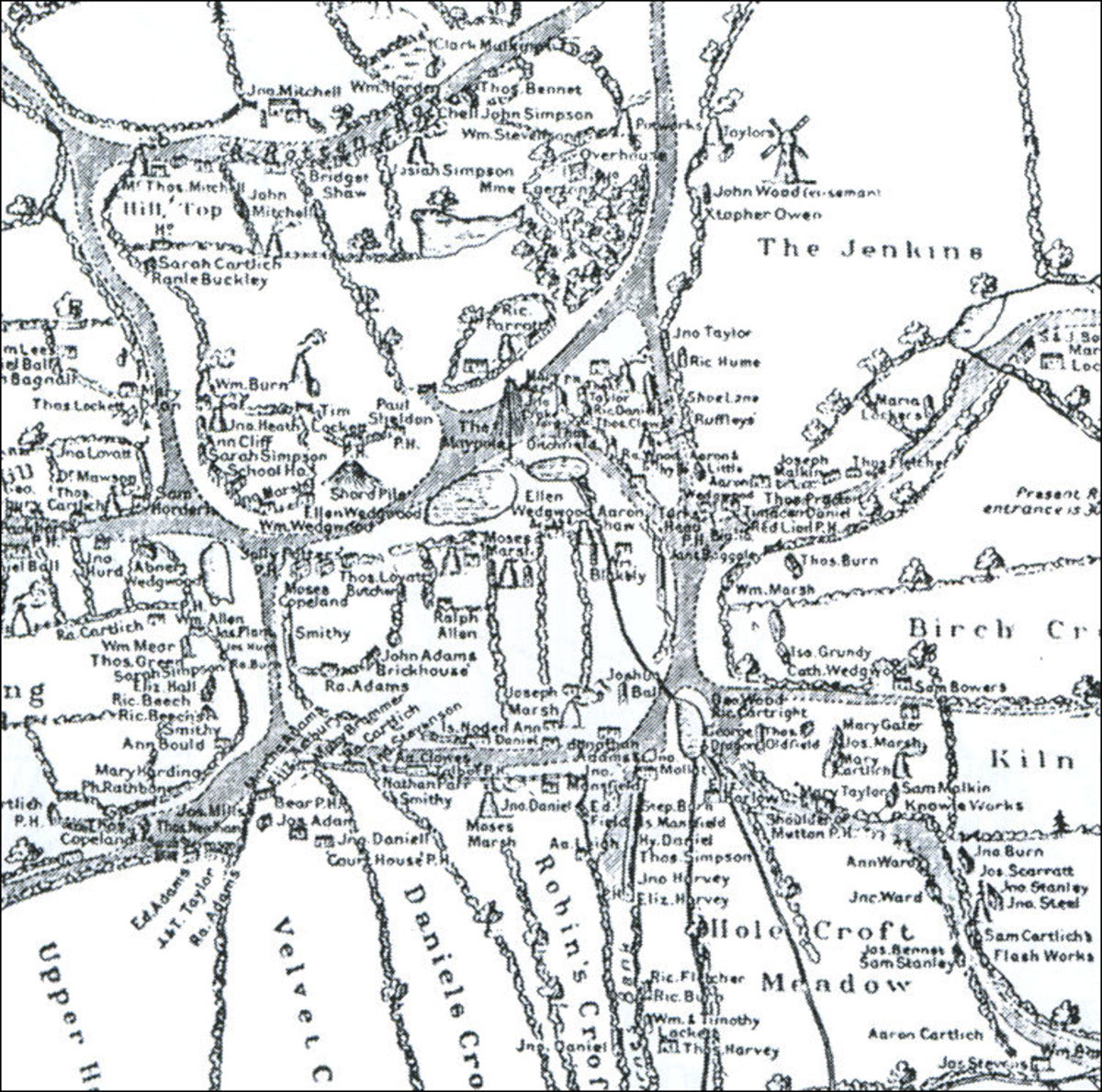

Jackfield Farm

Jackfield Farm in Molly's time would have sat in a rural area, surrounded by woods, moorland, mine shafts and marl holes, very different from the Burslem that we know today. The cottage itself was a long, low building, made of a half-timber frame, with a thatched roof. The windows were small and the roof was low, so it was probably quite dark in the cottage.

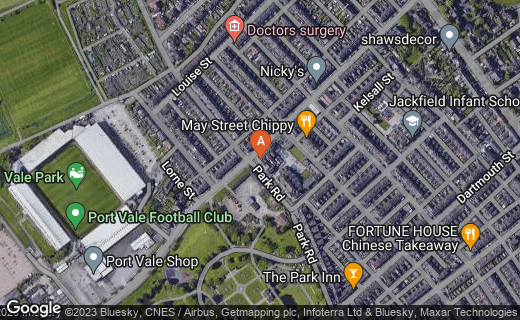

The modern-day area where the farm would have sat is at the junction of Hamil Road and Park Road, where the terraced houses now sit. Unfortunately, there is no trace of the farm or the cottage left.

After Molly's death in 1748, the farm seems to have ended up in the hands of Joseph Booth, her stepfather, which is the opposite of what Molly requested in her will. There is no evidence to say how Joseph ended up with Jackfield Farm. By 1760 the estate was held by the Bennett family and by the late 1830's John Bennett was the owner as well as the occupier.

While it is not known when the farm was built, we do know that it was demolished in 1894. After being in Molly's family for many years, she was the last of her line, as she was unmarried and childfree so the farm would have been sold on the death of her mother and step-father.

The Location of Jackfield Farm

Molly's Death and Grave Stone

Molly died in 1748 of seemingly natural causes but before she died, she wrote and signed her will, on March the 25th 1748. She was buried on the 1st of April.

Her funeral was led by the Reverend Spencer, who, it seems, was quite the drinker.

Interestingly, there is a record of someone who went to Molly's funeral and could remember what happened there. A relative, Ralph Leigh, who was 82 at the time of the conversation that was had with John Tellwright, 70.

In 1810, John Ward wrote a record, verbatim, of the two men talking in Burslem Market Place. They moved to the Turks Head, bought a round of gin and discussed many things, one of which was the funeral.

Here is the conversation, word for word, in the glorious, unaltered Potteries dialect, an extract from John Ward's book, The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent, written in 1810.

A Burslem Dialogue, from The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent by John Ward

Between JOHN TELWRIGHT and RALPH LEIGH.

(They meet in Burslem Market-place, 1810.)

(They go to the Turk's Head tavern, and Tellwright orders half a pint of gin, and two glasses.)

T. Rafe, Oi remember thi cuzzn Peggy, ut liv'd at th' Jack-feilt, an' wur berrid cross-weys i'th' church-yord. Oi hay oaff"n, when oi wur a yunker, scampurt at a pratty rate past th' church, freet'n't o' seein hur buggut.

L. Whoi hâi cudst be sitch a foo ? forgi' me, surry; bu' thee metst ha' bin shoor an sartin as håi th' ghost wur fast enuf leyd.

T. Nay, oi did no' know that onny hài; for they sed'n as hài hur wur only leyd for se'en year; bu' thee knows moore abait th' matter, Rafy.

L. Whoy, t' be sure, oi deu; for oi wur at th' berrin, an seed hur leyd queitly inuff i' th' greive, reet est an west. Bu when we aw geet'n back ogen to th' Hamill, ther wurn a pratty scootherin among th' beearers, for thoons as went'n furst into' th' håhis, seed'n her sittin' i'th' nook, knitin at a foin rate, as hur wur yoost to' ha' dun. Oi did no' see hur miseln; bu' paäsn Spencer, as berrit hur, wur fatch't, an he wur sartin o' th' truth on't; an he thout as hâi t' would be reet to ley th' ghost, an peacifoy foke's moinds. So th' next dey he insenst Madam Egerton abait it, an they aw wurn a gud jel moythurt; bu' at th' last, they agreed'n theyd'n hay sum moore paäsons to' help 'em t' ley th' ghost i' th' jed o'th neet; an come wurn gett'n to come.

T. Wal, Rafy, an dust know what they did'n?

L. Oi dunna reetly know hải they oss't;" bu Mester Spencer geet th' clark an th' saxon, wi' a lantern an candle, an they tuk'n up th' coffin, and they dug'n th' greive cross-weys, an leyd'n hur i' th' shape o' an oozel,+ as they sed'n, for seven year i' th' Red Sey.

T. An wheer wurn aw th' tuther paäs'ns at th' teyme?

L. It wur sed as hài they aw run'd owey, an laft'n paäs'n Spencer by hisseln to doo th' job. Oi then wur a big lad, an us'nt to milk th' kae ; an arter that oi wur fur sum teyme queit a feeart o' gooin i' th? shippon lest oi mit see hur ghost; an yet oi ne'er seed nout at aw.

T. Ah Rafe, oi've yerd th' oud paäso sey, he hoped ut he shud no' live for t' see the' seen yer àit.

L. Whoy dun yo' think he wur afeeart heo wud cum ogen arter th' teyme wur up?

T. For sartin he wur; an yet he livt till arter th' teyme, an oi nare yerd as hâi th' ghost e'er trubbl't him.

L. Whoy, Mester Terrick, th' oud paäsn wur rayther loike we han oaff'n bin. He wur fond o' a drap o' drink, an oim seure hisseln, an aw th' beearers wurn fuddlet afore they laft'n th' hâhis wi' th' berrin; an when they coom'n back ogen, oi guess they had no' gett'n queit sober and steyd.

T. Then, Rafy, thee thinks as hâi they cud no' see reet.

L. Oi s'pose they cud no'. Th' oud paäsn had yoost t' get boozy pratty off, an then he'd leigh asleep on the' alehus screen tin he geet sober ogen.

T. Yer naunt Molly, Rafe, wad be berrit cross-weys, as wur yer cuzzn, an oi moind as hai heo wur.

L. Aye, hur livt 20 year arter Peggy; an then th' toomston wur bilt as it nåi stonds at th' saith soide o' th' Church, craws-weys, for foke a gown at.

T. Wal, to be sure, it wur a queer consarn; an oi think oi've heerd, ut yer cuzzu's berrin wur on April-foo dey; so oi s'pose it wur an aw foos' job.

L. Whey, sartin sure it wur o'th' furst o' April, jist two year arter th' Scotch rebels coomn as fur as Baygna', (Bagnall), t' th' oud

There are a few things to take away from this conversation. The first is that they called her Peggy, which is short for Margaret. This gives a feeling of familiarity, which says that Molly was close with her family, as Ralph Leigh went to her funeral. It would make sense that the rest of her family and friends would have too, especially the ones in her will.

Another thing is that it seems many people at the funeral were drunk. They went on to the Turks Head after the funeral and then back to Molly's cottage. It is well known that the Reverend Spencer was not fond of Molly. So was he just drunk, or did he scare people with reports of her ghost to spite her?

The story of the Reverend and local 'Clark and Saxon digging her up and turning her around is very unlikely, as it would have been illegal for them to do this without the relevant documents and a court case at the Court of Chancery. It seems that people were just superstitious and easily lead by stories of witches and ghosts.

Her tombstone would have been erected a reasonable amount of time after her death, as in those days the stone would have been hand-cut and shaped by stonemasons and transported to the site. This would all have taken time and would have been very expensive.

The reason for her grave facing the other way is nothing to do with witchcraft. If Spencer had truly thought that Molly was a witch, she could not have been buried in consecrated ground. The reality is that people were buried where it was convenient. It was not unusual at that time for graves to face different ways. There are many examples of this across Stoke-on-Trent.

Wealth and Charity

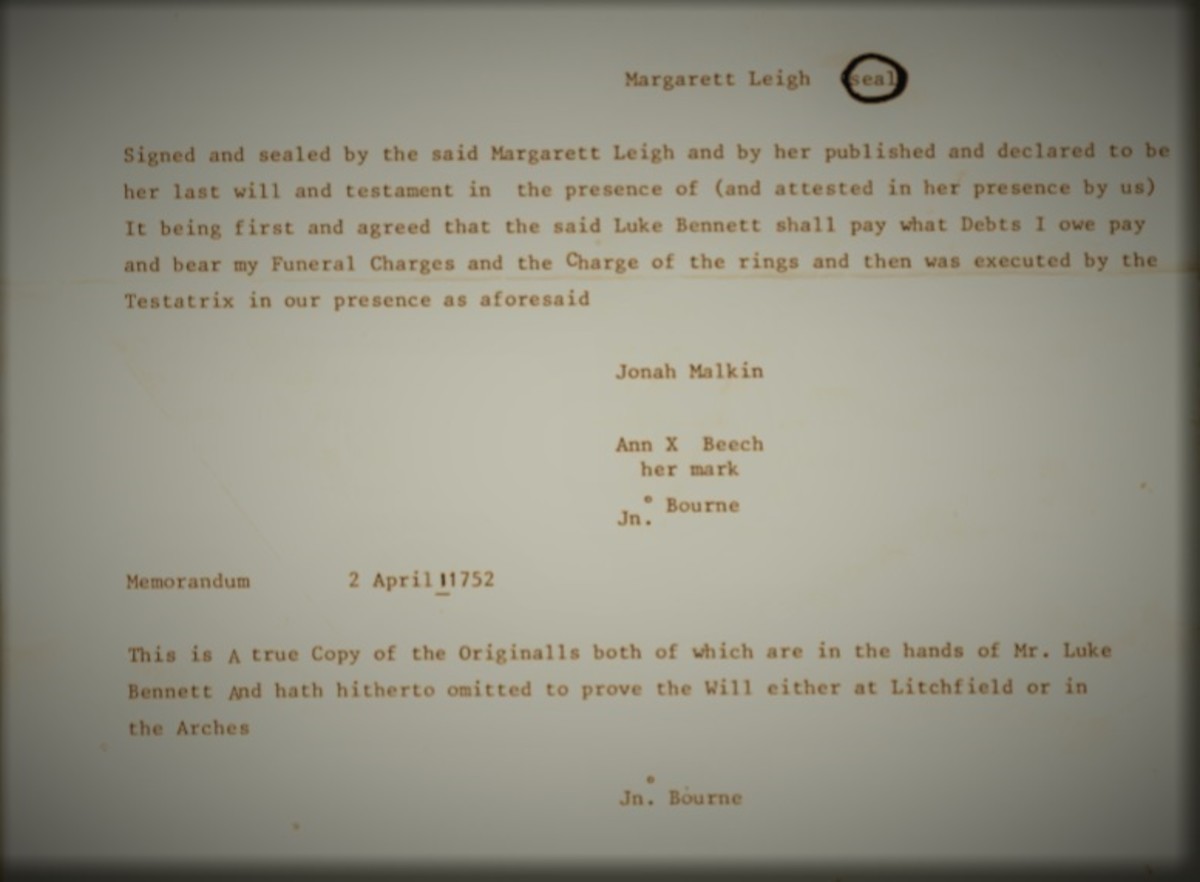

The last will and testament of Margarett Leigh had been privately owned for over 200 years and was returned to Stoke-on-Trent. A typed copy shows all of her assets and bequeathments.

It is dated March 25th the 21st year of the reign of King George II, which is just a few days before her death. She was buried on the 1st of April 1748.

Molly was a rather wealthy woman by the time of her death. She owned various estates and was a benefactor to the church and poor of Sneyd and Burslem. She left profits from her lands and forty-sixpenny loaves of bread yearly to be distributed 'amongst such of the poor Inhabitants and Widows for the time living within the Hamlett of Sneyd and Burslem'.

Money was left for the repair of monuments that were in the churchyard, and any leftover money from that was to also be distributed to the poor of the area.

Her mother, Mrs Sarah Booth, inherited all of the land and the farm at Jackfield and all of the income that it generated. She expressly ordered that her step-father (mistakenly called her father-in-law in the will) have nothing to do with any of it,

Her Aunt, Mrs Margarett Booker, was left a sum of £10 (Just under £2500 in 2021) every year for the remainder of her life.

To her friend Alice Beech, she left the parcel of land called Wall Flatt that she was already leasing from Molly.

After the death of her mother and aunt, she gives £20 a year (around £4500 in 2021) to her cousin Ann Donbavan for life to help her be sufficient without her husband.

She lists messuages (a dwelling house with its adjacent buildings and the lands appropriated to the use of the household) and lands in Jackfields, Norton parish, Wall Flatt, and Newbold Astbury in Chester.

After the death of the people listed in her will, she leaves £400 (nearly £90,000 in 2021) to be distributed between the children of her cousin Ann Donbavan. She leaves the lands in Chester to her other cousin Luke Bennett, and then onto his heirs.

Everything else was to then be sold for the best price that it can, and the money was to be used to build a hospital in Burslem for poor women and their ongoing maintenance and clothing of them. There is no evidence, however, that this hospital was ever built.

She also left her silver plate and utensils to her mother and a gold mourning ring to others in the family.

Finally, she asks that all of her estate debts and funeral expenses be paid for before anything was divided up.

The executors for the will were her cousin Luke Bennett and Mr Joseph Lovatt. Joseph was a man of high standing in Stoke-on-Trent, he was born in Green Head House, Penkhull (Now the Greyhound Inn) and was a well-educated man. Later in his life, he became the estate manager of Chirck Castle, Wales.

Molly's association with this man alone shows that she was of much higher social standing than previously thought. Add that to the properties and lands that she owned and it shows that Molly was a very independent, wealthy and business-minded woman.

This will also show us that not only was Molly a champion of the poor and downtrodden but she was also something of a feminist in her time. She gave her lands and money to the women in her family, to ensure that they were financially independent of the men in their lives. She also gave money to the poor women of the community and the funds for a hospital for women. She never married, and she was financially independent of men. So it seems that Molly was quite ahead of her time.

It is time to remember Molly Leigh for who she was. Time has played a cruel trick on her memory and it is time it is rectified.

Your Memories

If you have any further knowledge about Molly Leigh, her family or her life I would love to hear from you.

If you like what you have read, please feel free to support me by following and signing up for my newsletter and/or buying me a coffee!

Thank you.

If you are interested in the history of Burslem, then check out these books on Amazon.