Hidden in the depths of Derbyshire lies a beautiful little village with a poignant history.

Over 350 years ago, the rural village of Eyam, pronounced 'Eem', quarantined themselves in a famous act of self-sacrifice, to stop the Bubonic Plague from spreading to nearby towns and villages.

The Great Plague of London, which lasted from 1665 to 1666, was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to happen in England killing almost 25% of London's population in just over 18 months.

This plague was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which until recently was thought to have been spread by infected rat fleas, but recent research has shown that it was more likely, by how fast and how it spread, to have been spread by infected lice.

The Plague Arrives From London

In 1665 the local tailor, Alexander Hadfield, received a bundle of cloth from London. his assistant, George Viccars, was visiting Eyam to help make clothes for Wakes week, which is celebrated at the end of August and starts with the blessing of the wells.

George noticed that the bundle was damp and so he unfastened the bundle and spread all of the materials in front of the fire. It is thought that it was this action that unwittingly caused the fleas within the material to stir. These fleas were carrying the plague from London.

He soon became very ill and unfortunately died on the 7th September 1665, becoming the first victim in Eyam to die from the plague, but certainly not the last. His burial place is unfortunately unmarked.

Mary Hadfield's Plague Cottage

It didn't take long for the plague to take hold of the small, rural village. Within a few weeks, several more people had died. At first, the locals panicked, thinking that the pestilence that was upon them was the wrath of God punishing them for their sins. However, they soon realised that this was the plague and that it had probably come to them from London.

It is thought that in the first few weeks that more wealthy families fled the village, but there is no record of how many if any, actually left. The local people stayed, mainly because many had never left the village and did not have the funds to do so, nor did they have anywhere to go to.

By April 1666 there had been 73 deaths recorded from the plague and the villagers thought that the worst was over. However, with the warmth of Spring and Summer upon them, things went from bad to worse.

The local rector William Mompesson understood what was happening and tried to send his wife Catherine and their two children to safety. Catherine sent the children away and chose to stay to help her husband.

Mompesson was relatively new to the village and had not yet gained the respect of the villagers, so he worked alongside the former rector Thomas Stanley to come up with a plan for Eyam and it's inhabitants.

Eyam Parish Church, St Lawrence

Black Death Facts

- The plague itself has a death rate of 30%. The pneumonic phase rises to 90%

- It killed an estimated 50 million people

- 3-7 days is the average incubation period

- Three types of plague. Bubonic, septicaemic and pneumonic

- Bubonic, with painful swollen lymph nodes known as buboes, is the most common

- Plague is still endemic in some countries

The Reverend William Mompesson

Quarantine

Mompesson knew that the only way to stop the plague from spreading was to keep people away from each other. So they quarantined the village.

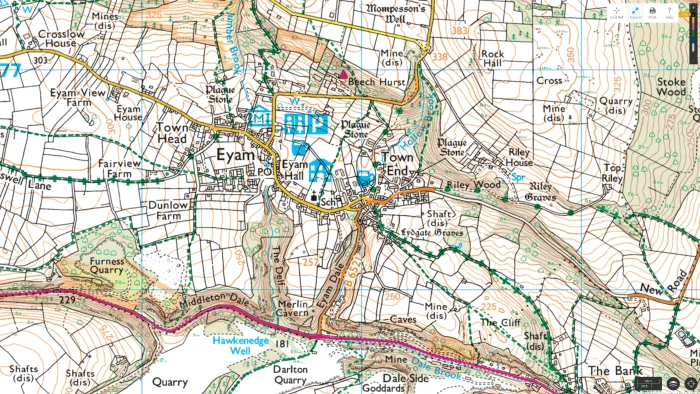

The village itself, however, was not self-sufficient, so plans had to be made to stock the village safely. The Earl of Devonshire, who resided at nearby Chatsworth House, agreed to be the chief benefactor and to supply the village with food and medicine. It was agreed that the supplies would be left at the southern boundary of the village at the boundary stone. Holes were drilled into the top of the stone and filled with vinegar to disinfect the coins left. They also used another place to trade in the same way which is now known as Mompesson's Well.

Other precautions were also taken, the church was closed and services postponed. The services took place outdoors at Cucklet Delph where the parishioners could stand away from each other. Burials were also stopped, meaning that families had to bury their own dead in gardens or local fields.

The Boundary Stone

An Attempted Escape

In July 1666 an unknown woman, who lived at Town Head in one of the houses set back from the road, walked the 5 miles to Tideswell to escape the horror and hopefully live safely.

She knew that the village would be busy on market day, however, to enter the village she would have to get past the parish constable.

In order to stop the plague from entering the village, a constable had been posted at the eastern entrance to check who was coming into the village. When she was asked where she came from, she answered honestly that she was from Orchard Bank, which is where she came from in Eyam. The guard didnt know where it was and allowed her into the village.

She had almost reached the market when she was recognised by a local woman who let up a cry of 'the plague! The plague! A woman is here from Eyam!". The villagers proceeded to pelt the woman with mud, vegetables, stones and anything else they could get their hands on and chased her nearly a mile out of the village.

On arrival back at the village the Reverend Stanley said that she was much chastened and a 'sadder but wiser woman'.

Elizabeth Hancock

The Sacrifice of the People

On their own, with no outside help, the villagers must have been terrified. The death toll quickly mounted, yet the villagers stayed inside the quarantine area.

By August 1666 5/6 people a day were dying. The loss of life was horrific. Elizabeth Hancock was the sole survivor of her household. She lost her husband and her 6 children one after the other over 8 days in August 1666 at the height of the plague. To make it worse she had to drag each of their bodies up to the field near Riley Wood, to bury them herself, alone. People from the neighbouring Stoney Middleton watched on across the hill, too afraid to break the cordon sanitaire to help her.

The Riley Graves Tomb Inscription

REMEMBER MAN, AS THOU GOEST BY, AS THOU ART NOW, EVEN ONCE WAS I, AS I DOE NOW, SO MUST THOU LYE. REMEMBER MAN THAT THOU MUST DIE.

— Inscription on the Riley Graves table tomb

The Riley Graves

Marshall Howe, a local man, took it upon himself to bury the bodies of those taken by the plague. His payment was taking the possessions of the dead. He lost his wife on August 27th 1666 and his son 3 days later and he had to bury them himself. Marshall was infected with the plague early on but survived.

Mary Hadfield, who was the wife of Alexander Hadfield, the tailor at the beginning of this story, survived but lost a staggering 13 of her relatives.

William Mompesson and his wife Catherine were out for a walk one day in August in the hills surrounding the village when she spoke about the sweet smell in the air. Mompesson knew what this meant and sure enough the next morning, August the 22nd 1666, she died, aged 27.

Medical knowledge was poor in the 17th century so the villagers relied upon the knowledge and help of local herbalist Humphrey Merrill. He died in September 1666, his wife survived. He is buried behind his house and a tombstone marks his grave.

Andrew Merrill, who shared the house with Humphrey and his wife, avoided the plague entirely by going to the edge of Eyam Moor and building a small hut to live in with his pet cockerel until the it had gone.

Humphrey Merrill's Grave

The Tomb of Catherine Mompesson

Survival and the Lasting Legacy

The last victim to die of the plague in Eyam was Abraham Morton of Shepherds Flat, he died on the 1st November 1666. In total, the plague lasted around 14 months in Eyam, and killed around 260 people, with 76 families affected.

The selfless act of these simple, rural people worked. The plague did not spread to any other local towns or villages. Their sacrifice is remembered in the village with plaques on all of the buildings affected by the plague, naming the people that lived, and died, inside them. 'Plague Sunday' has been celebrated since the bicentenary of the plague in 1866. It takes place in Cucklet Delph on the last Sunday of August so that it coincides with the Wakes Week and well dressing. Catherine Mompesson's tabletop grave in the churchyard also has a wreath laid on it each Plague Sunday to remember her devotion to her husband and the village, and ultimately, her sacrifice.

Three and a half centuries later we remember them and we can learn much from them. The quarantine restrictions genuinely worked, the local towns and villages were spared from the pestilence. Even then, over 300 years ago, they knew that the best way to avoid becoming ill and spreading the illness was to stay away from each other. They made the ultimate self-sacrifice and saved many others in doing so.

Plague Sunday

If you like what you have read, please feel free to support me by following and signing up for my newsletter and/or buying me a coffee!

Thank you.

If you are interested in the history of Eyam and the plague then check out these books on Amazon.